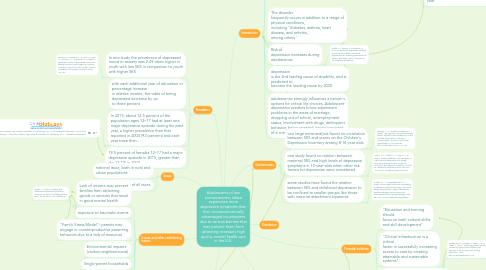

1. Prevalence

1.1. In one study the prevalence of depressed mood or anxiety was 2.49 times higher in youth with low SES in comparison to youth with higher SES

1.1.1. Lemstra, M., Neudorf, C., D'Arcy, C., Kunst, A., Warren, L. M., & Bennett, N. R. (2008). A systematic review of depressed mood and anxiety by SES in youth aged 10-15 years. Canadian Journal of Public Health / Revue Canadienne De Sante'e Publique, 99(2), 125-129.

1.2. with each additional year of education or percentage increase in relative income, the odds of being depressed decrease by up to three percent

1.3. In 2015, about 12.5 percent of the population ages 12–17 had at least one major depressive episode during the past year, a higher prevalence than that reported in 2004 (9.0 percent) and each year since then.

1.3.1. America's Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2017. (n.d.). Retrieved February 07, 2018, from Childstats.gov - America's Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2017 - Adolescent Depression

1.4. 19.5 percent of females 12–17 had a major depressive episode in 2015, greater than the 13.1% in 2004

2. Scope

2.1. national issue, both in rural and urban populations

2.2. affects males and females of all races

3. Trends

3.1. there is no evidence for an increased prevalence of child or adolescent depression over the past 30 years. Public perception of an ‘epidemic’ may arise from heightened awareness of a disorder that was under-diagnosed for a long time

3.1.1. Costello, E. J., Erkanli, A., & Angold, A. (2006). Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(12). doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x

3.2. worse in females and getting worse in females

4. Causes and other contributing factors

4.1. Lack of income may prevent families from obtaining goods or services that result in good mental health

4.1.1. Butler, A. C. (2014). Poverty and adolescent depressive symptoms. American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry, 84(1), 82-94. doi:10.1037/h0098735

4.2. exposure to traumatic events

4.3. "Family Stress Model"- parents may engage in counterproductive parenting behaviors due to a lack of resources

4.4. Environmental impacts (violent neighborhoods)

4.5. Single-parent households

4.6. Stigma about receiving mental health care may be worse in low-SES communities

4.7. poor parental mental health

5. Introduction

5.1. Although there is a great need for mental health care, families in poverty are the least likely population to receive high-quality mental health care.

5.1.1. Hodgkinson, S., Godoy, L., Beers, L. S., & Lewin, A. (2017). Improving Mental Health Access for Low-Income Children and Families in the Primary Care Setting. Pediatrics, 139(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1175

5.2. The long-term negative effects of adolescent depression

5.2.1. for the adolescent

5.2.2. for society as a whole (e.g. economically)

5.2.2.1. Goodman, E., Slap, G. B., & Huang, B. (2003). The Public Health Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Adolescent Depression and Obesity. American Journal of Public Health, 93(11), 1844–1850.

5.2.2.2. costs attributable to depression are estimated 98.9 Billion dollars per year

5.3. The disorder frequently occurs in addition to a range of physical conditions, including "diabetes, asthma, heart disease, and arthritis, among others"

5.4. Risk of depression increases during adolescence

5.4.1. Uddin, M., Jansen, S., & Telzer, E. H. (2017). Adolescent depression linked to socioeconomic status? molecular approaches for revealing premorbid risk factors. Bioessays, 39(3), 1600194-n/a. 10.1002/bies.201600194

5.5. depression is the 2nd leading cause of disability, and is predicted to become the leading cause by 2030

5.6. adolescence strongly influences a person's options for critical life choices. Adolescent depression predicts future adjustment problems in the areas of marriage, dropping out of school, unemployment status, involvement with drugs, delinquent behavior, being arrested, being convicted of a crime, and being in a car accident

6. Controversies

6.1. one large meta-analysis found no correlation between SES and scores on the Children's Depression Inventory among 8-16 year olds

6.1.1. Twenge, J. M., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2002). Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort difference on the children's depression inventory: A meta-analysis. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology, 111(4), 578-588. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.578

6.2. one study found no relation between maternal SES and high levels of depressive symptoms in 10-year-olds when other risk factors for depression were considered

6.2.1. Leech, S. L., Larkby, C. A., Day, N. L., & Day, R. (2006). Predictors and correlates of high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms among children at age 10. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(2), 223-230. 10.1097/01.chi.0000184930.18552.4d

6.3. some studies have found the relation between SES and childhood depression to be confined to smaller groups like those with insecure attachment toparents

6.3.1. Graham, C. A., & Easterbrooks, M. A. (2000). School-aged children's vulnerability to depressive symptomatology: The role of attachment security, maternal depressive symptomatology, and economic risk. Development and Psychopathology, 12(2), 201-213. 10.1017/S0954579400002054

7. Recommended preventive measures

8. Potential solutions

8.1. "Education and training should focus on both cultural shifts and skill development"

8.2. "Clinical infrastructure is a critical factor in successfully increasing access to care by creating attainable and sustainable systems"

8.2.1. Hodgkinson, S., Godoy, L., Beers, L. S., & Lewin, A. (2017). Improving Mental Health Access for Low-Income Children and Families in the Primary Care Setting. Pediatrics, 139(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1175