1. Politics of Education

1.1. The Purposes of Schooling

1.1.1. Intellectual - Teaching basic cognitive skills such as reading, writing, and mathematics to transmit specific knowledge.

1.1.2. Political - To generate allegiance to the existing political order and to prepare citizens to participate in this political order.

1.1.3. Social - To help solve societal problems in order to work in one of many institutions to ensure social cohesion.

1.1.4. Economic - To prepare students for their future occupation and to train and allocate individuals into the division of labor.

1.2. Political Perspectives

1.2.1. Conservative Perspective

1.2.1.1. The strongest individuals and/or groups survive. Human progress is dependent on individual initiative and drive.

1.2.1.2. Capitalism is most economically productive and the system that is most respective of human needs. Market capitalism allows for maximum economic growth with competition insuring abuses can be minimized.

1.2.1.3. Stresses individual initiative; the individual is the only one capable of solving his or her problems.

1.2.2. Liberal Perspective

1.2.2.1. Although believing in a market capitalist economy, understands that the capitalist economy is prone to cycles of recession that must be addressed by government intervention.

1.2.2.2. Government involvement in economic political and social matters is necessary to insure a healthy economy.

1.2.2.3. Concerned primarily with balancing the economic productivity of capitalism with the social and economic needs of the majority of people.

1.2.2.4. Stresses that groups rather than individuals are effected by the structure of society so solutions to social problems must address group dynamics rather than individuals alone.

1.2.3. Radical Perspective

1.2.3.1. Believes democratic socialism is a better political economic system than free market capitalism. "Capitalism will ultimately lead to socialism."

1.2.3.2. Essential belief that social problems such as poverty and educational problems of poor citizens are endemic to capitalsim.

1.2.3.3. "Only a transformation of capitalism into democratic socialism will ensure that the social problems that affect the disadvantaged in society will be addressed."

1.2.3.4. Social problems are structural in nature, therefore the solutions must be addressed to this structure, not at individuals.

2. History of U.S. Education

2.1. The Age of Reform (1820-1860)

2.1.1. Public Education moved toward a secular curriculum.

2.1.2. Horace Mann establishes the common school (free publicly funded elementary schools).

2.1.3. The first teacher training school was established in Lexington, Massachusetts (1839).

2.1.4. Higher education for women made great leaps. Mary Lyon founded Mt. Holyoke seminary in 1837. The entry level requirements and level of instruction were the same for women as for men.

2.2. Conservative Perspectives

2.2.1. Argued that U.S. students knew very little and that U.S. schools were mediocre.

2.2.2. Conservative critic Diane Ravitch argued that the preoccupation with using education to solve social problems has not solved these problems and, simultaneously, has led to the erosion of educational excellence.

2.2.3. According to Ravitch, the progressive reforms of the twentieth century denigrated the traditional role of schools in passing on a common culture and produced a generation of students who know little, if anything, about their Western heritage.

2.2.4. Allan Bloom blames the universities for watering down their curriculums; E. D. Hirsch Jr. blames the public schools for valuing skills over content; and William Bennett, in his role as Secretary of Education during the Reagan administration, called for a return to a traditional Western curriculum.

3. Sociological Perspectives

3.1. Theoretical Perspectives

3.1.1. Functional Theories

3.1.1.1. Functionalists view society as a kind of machine, where one part articulates with another to produce the dynamic energy required to make society work.

3.1.1.2. Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) believed that education, in virtually all societies, was of critical importance in creating the moral unity necessary for social cohesion and harmony.

3.1.1.3. Tend to assume that consensus is the normal state in society and that conflict represents a breakdown of shared values.

3.1.2. Conflict Theories

3.1.2.1. Some sociologists argue that the social order is not based on some collective agreement, but on the ability of dominant groups to impose their will on subordinate groups through force, cooptation, and manipulation.

3.1.2.2. Does not see the relation between school and society as unproblematic or straightforward.

3.1.2.3. From a conflict point of view, schools are similar to social battlefields, where students struggle against teachers, teachers against administrators, and so on.

3.1.3. Interactional Theories

3.1.3.1. Primarily critiques and extensions of the functional and conflict perspectives.

3.1.3.2. Interactional theories attempt to make the commonplace strange by turning on their heads everyday taken-for-granted behaviors and interactions between students and students, and between students and teachers.

3.1.3.3. States that it is exactly what one does not question that is most problematic at a deep level.

3.2. Effects of Schooling on Individuals

3.2.1. Knowledge and Attitudes

3.2.1.1. It has been found that the actual amount of time students spend in school is directly related to how much they learn.

3.2.1.2. More highly educated people are also more likely to be liberal in their political and social attitudes.

3.2.1.3. The effective schools research demonstrates that academically oriented schools do produce higher rates of learning.

3.2.2. Employment

3.2.2.1. Research has shown that large organizations, such as corporations, require high levels of education for white-collar, managerial, or administrative jobs (Collins, 1971).

3.2.2.2. Credential inflation has led to the expectation among employers that their employees will have an ever-increasing amount of formal education.

3.2.2.3. Surprisingly, research has shown that the amount of education is only weakly related to job performance. From this evidence, it seems clear that schools act as gatekeepers in determining who will get employed in high-status occupations, but schools do not provide significant job skills for their graduates.

3.2.3. Education and Mobility

3.2.3.1. In general, most Americans believe that more education leads to economic and social mobility; individuals rise and fall based on their merit.

3.2.3.2. The number of years of education is one measure of educational attainment, but where people go to school also affects their mobility.

3.2.3.3. For some groups, such as the middle class, increased education may be directly linked to upward occupational mobility; for the rich and poor, education may have little to do with mobility.

3.3. Inside the Schools

3.3.1. Teacher Behavior

3.3.1.1. Teachers have a huge impact on student learning and behavior.

3.3.1.2. Persell (1977) found that when teachers demanded more from their students and praised them more, students learned more and felt better about themselves.

3.3.1.3. Research indicates that many teachers have lower expectations for minority and working-class students; this suggests that these students may be trapped within a vicious cycle of low expectation-low achievement-low expectation. In part, this cycle of failure may be responsible for high dropout rates and failure to achieve at grade level.

3.3.2. Student Peer Groups and Alienation

3.3.2.1. In a sense, the adult culture of the teachers and administrators is in conflict with the student culture. This conflict can lead to alienation and even violence.

3.3.2.2. Stinchcombe (1964) found, for instance, that students in vocational programs and headed toward low-status jobs were the students most likely to join a rebellious subculture.

3.4. Education and Inequality

3.4.1. Inadequate Schools

3.4.1.1. Urban education, in particular, has failed to educate minority and poor children.

3.4.1.2. Students who attend suburban schools and private schools get a better educational experience than other children (Coleman, Hoffer, & Kilgore, 1982).

3.4.1.3. Students who attend the most elite private schools obtain substantial educational benefits, both in terms of their actual educational experience and the social value of their diplomas.

3.4.2. Tracking

3.4.2.1. Refers to the placement of students in curricular programs based on students' abilities and inclinations.

3.4.2.2. It has been found in many thorough studies that tracking decisions are often based on other criteria, such as students' class or race.

3.4.2.3. Moreover, track placement directly affects cognitive development (Rosenbaum, 1976). Students in lower tracks experience more alienation and authoritarian teachers than high-track students.

3.4.3. De Facto Segregation

3.4.3.1. One study found that African-Americans from low-income communities who attended racially mixed schools were more likely to graduate from high school and college than similar African-American children who attended segregated schools.

3.4.3.2. Moreover, African-American students who attended integrated schools were less likely to be arrested by the police, more likely to live in desegregated neighborhoods, and women were less likely to have a child before the age of 18.

3.4.3.3. Thus, racial integration at the school level seems to be beneficial to minority students, and there is no conclusive evidence that majority students are harmed by integration.

3.4.4. Gender

3.4.4.1. Although girls usually start school cognitively and socially ahead of boys, by the end of high school, girls have lower self-esteem and lower aspirations than do boys.

3.4.4.2. Traditionally, textbooks have been biased against women by ignoring their accomplishments and social contributions.

3.4.4.3. Over the past two decades the gender gap in academic achievement has all but disappeared, with female students outperforming males in language arts and social studies, and closing the gaps significantly in mathematics, sciences, and having higher college attendance rates, albeit much lower participation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) disciplines. (Arnot, David, & Weiner, 1999; Borman, Tyson, & Halperin, 2010; Buchmann, 2009; Buchmann, DiPrete, & McDaniel, 2008).

4. Philosophy of Education

4.1. Idealism

4.1.1. Generic Notions

4.1.1.1. According to Plato, matter was an inaccurate measurement of truth since it was constantly changing.

4.1.1.2. The only constant for Plato was the field of mathematics, since 1 + 1 = 2 will never change.

4.1.1.3. Since Platos' time, people have witnessed how increasingly the school and tracking, in particular, determine the life chances of students.

4.1.2. Key Researchers

4.1.2.1. Plato

4.1.2.2. St. Augustine (354-430 A.D.)

4.1.2.3. René Descartes (1596-1650), Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831)

4.1.3. Goal of Education

4.1.3.1. Interested in the search for truth through ideas rather than through the examination of the false shadowy world of matter.

4.1.3.2. Teachers encourage students to search for truth as individuals.

4.1.3.3. Subscribes to the notion that education in transformation: Ideas can change lives.

4.1.4. Role of the Teacher

4.1.4.1. Analyze and discuss ideas with students in order for students to move to new levels of awareness so that ultimately they can be transformed.

4.1.4.2. Deal with abstract notions through the dialect method but should aim to connect analysis with action as well.

4.1.4.3. The teacher sees themselves as a role model in the classroom, to be emulated by others.

4.1.5. Methods of Instruction

4.1.5.1. Teachers take part in the students' learning.

4.1.5.2. Although they lecture from time to time, perhaps to fill in background material not covered in the reading, they predominantly use the dialectic approach.

4.1.5.3. Students are encouraged to work in groups or individually on research projects, both oral and written.

4.1.6. Curriculum

4.1.6.1. Idealists place great importance on the study of classics such as the Magna Carta, etc.

4.1.6.2. For idealists, all contemporary problems have their roots in the past and can be best understood by examining how previous individuals dealt with them.

4.1.6.3. Many idealists also support a back-to-basics approach to education, which emphasizes the three R's (Reading, writing, arithmatic).

4.2. Realism

4.2.1. Generic Notions

4.2.1.1. Aristotle believed that only through studying the material world was it possible for an individual to clarify or develop ideas.

4.2.1.2. Realists reject the Plutonic notion that only ideas are real, and argue instead that the material world or matter is real.

4.2.1.3. Realists hold that matter exists, independent of ideas.

4.2.2. Key Researchers

4.2.2.1. Religious realism - Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

4.2.2.2. Modern realism - Francis Bacon (1561-1626), John Locke (1632-1704)

4.2.2.3. Contemporary realism - Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947), Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)

4.2.3. Goal of Education

4.2.3.1. Understand ideas through studying the world of matter.

4.2.3.2. Help individuals understand and then apply the principles of science to help solve the problems plaguing the modern world.

4.2.3.3. Through basic disciplines - and in particular, science - individuals will be able to fathom what philosophers have been debating since the beginning of their discipline: existence of the good life, but thanks to Aristotle, how it can be encouraged through science.

4.2.4. Role of the Teacher

4.2.4.1. According to contemporary realists, teachers should be steeped in the basic academic disciplines in order to transmit to their students the knowledge necessary for the continuance of the human race.

4.2.4.2. Have a solid grounding in science, mathematics, and the humanities.

4.2.4.3. Enable students to learn objective methods of evaluating such works as art, music, poetry, and literature.

4.2.5. Methods of Instruction

4.2.5.1. Lecture, and Q&A.

4.2.5.2. Support lecture as a method of instruction in order to give students the knowledge necessary to make evaluations of artistic and literary works.

4.2.5.3. Competency-based assessment.

4.2.6. Curriculum

4.2.6.1. Science and math, reading and writing, and the humanities.

4.2.6.2. This body of knowledge is viewed as being essential for the survival of society.

4.3. Pragmatism

4.3.1. Generic Notions

4.3.1.1. The school became an "embryonic community" where children could learn skills both experientially as well as from books, in addition to traditional information, which would enable them to work cooperatively in a democratic society.

4.3.1.2. Dewey's ideas about education proposed that educators start with the needs and interests of the child in the classroom, allow the child to participate in planning his or her course of study, employ project method or group learning, and depend heavily on experiential learning.

4.3.1.3. Dewey's progressive methodology rested on the notion that children were active, organic beings, growing and changing.

4.3.2. Key Researchers

4.3.2.1. George Sanders Peirce (1839-1914)

4.3.2.2. William James (1842-1910)

4.3.2.3. John Dewey (1859-1952)

4.3.3. Goal of Education

4.3.3.1. Dewey stressed the importance of the school as a place where ideas can be implemented, challenged, and restructured.

4.3.3.2. Schooling must be understood as part of the larger project of social progress and improvement.

4.3.3.3. Schools should balance the needs of society and community on one hand and the needs of the individual on the other.

4.3.4. Role of the Teacher

4.3.4.1. The teacher is no longer the authoritarian figure from which all knowledge flows.

4.3.4.2. The teacher assumes the peripheral position of facilitator.

4.3.4.3. The teacher also writes curriculum and must have a command of several disciplines in order to create and implement curriculum.

4.3.5. Methods of Instruction

4.3.5.1. Formal instruction is abandoned.

4.3.5.2. Problem-solving or inquiry method.

4.3.5.3. Carefully orchestrated classroom with children going about learning in nontraditional yet natural ways.

4.3.6. Curriculum

4.3.6.1. Progressive schools generally follow Dewey's notion of a core curriculum, or and integrated curriculum.

4.3.6.2. Progressive educators support starting with contemporary problems and working from the known to the unknown, or what is now called in social studies education, "the curriculum of expanding environments."

4.3.6.3. Progressive educators are not wedded to a fixed curriculum either; rather, curriculum changes as the social order changes and as children's interests and needs change.

4.4. Existentialism

4.4.1. Generic Notions

4.4.1.1. Existentialists pose questions as to how their concerns impact on the lives of individuals.

4.4.1.2. Believe that individuals are placed on this earth alone and must make some sense out of the chaos they encounter.

4.4.1.3. People must create themselves, and they must create their own meaning.

4.4.2. Key Researchers

4.4.2.1. Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

4.4.2.2. Martin Buber (1878-1965), Karl Jaspers (1883-1969), Jean Paul Sartre (1905-1986)

4.4.2.3. Contemporary philosopher Maxine Greene

4.4.3. Goal of Education

4.4.3.1. Focus on the needs of individuals, both cognitively and affectively.

4.4.3.2. Stress Individuality.

4.4.3.3. Include discussion of the non-rational as well as the rational world.

4.4.4. Role of the Teacher

4.4.4.1. Teachers should understand their own "lived worlds" as well as that of their students in order to help their students achieve the best "lived worlds" they can.

4.4.4.2. Must take risks; expose themselves to resistant students; and work constantly to enable their students to become, in Greene's words (1978), "wide awake."

4.4.4.3. Introspection is useful in order to enable students to become in touch with their worlds and to empower them to choose and to act on their choices.

4.4.5. Methods of Instruction

4.4.5.1. Learning is viewed as intensely personal.

4.4.5.2. Each child has a different learning style and it is up to the teacher to discover what works for each child.

4.4.5.3. The teacher constantly rediscovers knowledge, the student discovers knowledge, and together they come to an understanding of past, present, and future, particularly a future ripe with possibilities.

4.4.6. Curriculum

4.4.6.1. Heavily biased toward the humanities.

4.4.6.2. Believe in exposing students at early ages to problems as well as possibilities, and to the horrors as well as accomplishments humankind is capable of producing.

4.4.6.3. Literature is able to evoke responses in readers that might move them to new levels of awareness.

4.5. Neo-Marxism

4.5.1. Generic Notions

4.5.1.1. Marx' voluminous life's work concerned the understanding of capitalism.

4.5.1.2. Marx believed that the history of civilization was defined by class struggle - the struggle between the dominant economic group and subordinate economic groups.

4.5.1.3. Although Marx indeed believed that economic laws are the foundations of society, it is people, through conflict and struggle, who make history.

4.5.2. Key Researchers

4.5.2.1. Karl Marx (1818-1883)

4.5.2.2. Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis (1976)

4.5.2.3. Paulo Freire (1972) and Henry Giroux (1983b)

4.5.3. Goal of Education

4.5.3.1. Reproduction theories argue that the role of education in capitalist societies is to reproduce the economic, social, and political status quo.

4.5.3.2. Resistance theories, while agreeing that schools often reproduce the dominant ideology, state they also have the potential to empower students to question it.

4.5.3.3. Education should transform the dominant culture.

4.5.4. Role of the Teacher

4.5.4.1. The teacher must become a "transformative intellectual" (Giroux, 1988) whose role is to engage their students in a critical examination of the world.

4.5.4.2. The student thus becomes a part of the educational process that seeks to examine critically the society and its problems and to seek radical alternatives.

4.5.5. Methods of Instruction

4.5.5.1. Dialectical approach to instruction.

4.5.5.2. The goal of instruction is to reveal underlying assumptions of society and to help students see alternative possibilites.

4.5.6. Curriculum

4.5.6.1. Curriculum is not objective or value free but is socially constructed.

4.5.6.2. The curriculum is the organized and codified representation of what those with the power to shape it want the children to know.

4.5.6.3. Individuals can reshape the curriculum to represent a fairer view of the world.

4.6. Postmodernist

4.6.1. Generic Notions

4.6.1.1. Stresses the necessary connection between theory and practice as a corrective to the separation of them in much modernist thought.

4.6.1.2. All social and political discourse is related to structures of power and domination.

4.6.1.3. Calls for the attempt to work through differences, rather than to see them as hopelessly irreconcilable.

4.6.2. Key Researchers

4.6.2.1. Derrida (1981, 1982) and Baudrillard (1981, 1984)

4.6.2.2. Aronowitz & Giroux, 1991; Harvey, 1989; Jameson, 1982; Jencks, 1987; Lyotard, 1984

4.6.2.3. Cherryholmes, 1988; Ellsworth, 1989; Lather, 1991; McLarren & Hammer, 1989; Wexler, 1987

4.6.3. Goal of Education

4.6.3.1. Calls for teachers and students to explore the differences between what may seem like inherently contradictory positions in an effort to achieve understanding, respect, and change.

4.6.3.2. Transform teachers, schools, and ultimately society.

4.6.4. Role of the Teacher

4.6.4.1. Stresses the classroom as a site for political action and teachers as agents of change.

4.6.5. Methods of Instruction

4.6.5.1. Focus on postmodern concerns with difference in a politically transformative manner.

4.6.5.2. Concern for difference needs to be translated into a critical language that allows for competing discourses and that rejects any master narratives or curriculum canons.

4.6.6. Curriculum

4.6.6.1. Ethics is a central concern.

4.6.6.2. Students need to understand the social construction of different voices and identities.

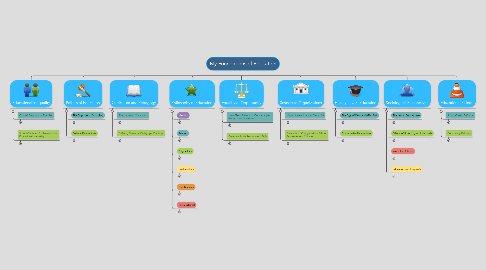

5. Schools as Organizations

5.1. Major Stakeholders in District 08

5.1.1. Senators

5.1.1.1. Richard Shelby

5.1.1.2. Luther Strange

5.1.2. House of Representatives

5.1.2.1. Mo Brooks

5.1.3. State Superintendent

5.1.3.1. Michael Sentence

5.1.4. Representative on State School Board

5.1.4.1. Mary Scott Hunter

5.1.5. Local Superintendent

5.1.5.1. Trey Holladay

5.1.6. Local School Board

5.1.6.1. Chairman - Mr. Russell Johnson

5.1.6.2. Vice Chairman - Mrs. Beverly Malone

5.1.6.3. Board Member - Mr. Tim Green

5.1.6.4. Board Member - Mr. Michael Scott Henry

5.1.6.5. Board Member - Mr. James Lucas

5.1.6.6. Board Member - Mrs. Jennifer Manville

5.1.6.7. Board Member - Dr. Christopher Browning Paysinger

5.2. Elements of Change Within School Processes and Cultures

5.2.1. Conflict

5.2.1.1. Conflicts allow previously hidden issues to surface.

5.2.1.2. Staff involvement in school restructuring must be prepared to manage and resolve conflicts.

5.2.2. New Behaviors

5.2.2.1. Change requires new relationships and behaviors.

5.2.2.2. The change process must include building communication and trust, enabling leadership and initiative to emerge, and learning techniques of communication, collaboration, and conflict resolution.

5.2.3. Team Building

5.2.3.1. Team building must extend to the entire school.

5.2.3.2. Shared decision making must consciously work out and give on-going attention to relationships within the rest of the school's staff.

5.2.4. Process and Content

5.2.4.1. Process and content are interrelated.

5.2.4.2. The process a team uses in going about its work is as important as the content of educational changes it attempts.

5.2.4.3. The usefulness and the visibility of a project will influence future commitments from and the relationships among the staff and others involved.

6. Curriculum and Pedagogy

6.1. The Humanist Curriculum

6.1.1. Reflects the idealist philosophy that knowledge of the traditional liberal arts is the cornerstone of an educated citizenry and that the purpose of education is to present to students the best of what has been thought and written.

6.1.2. Does not necessarily have to strictly be western traditions that are taught.

6.1.3. Focuses on English, foreign languages, mathematics, history, and science.

6.2. Differing Views on Pedagogic Practices

6.2.1. The Mimetic Tradition

6.2.1.1. Based on the viewpoint that the purpose of education is to transmit specific knowledge to students.

6.2.1.2. Utilizes the didactic method. A method that commonly relies on the lecture or presentation as the main form of communication.

6.2.1.3. Assumes that the educational process involves the relationship between the knower (the teacher) and the learner (the student), and that education is a process of transferring information from one to the other.

6.2.2. The Transformative Tradition

6.2.2.1. Defines the function of education more broadly and, according to some, more ambiguously.

6.2.2.2. Proponents of this tradition believe that the purpose of education is to change the student in some meaningful way, including intellectually, creatively, spiritually, and emotionally.

6.2.2.3. Transformative educators do not see the transmission of knowledge as the only component of education and thus they provide a more multidimensional theory of teaching.

7. Equality of Opportunity

7.1. How Class, Race, and Gender Impact Educational Outcomes

7.1.1. Class

7.1.1.1. Education is extremely expensive and the longer a student stays in school, the more likely he or she needs parental financial support.

7.1.1.2. Families from the upper and middle classes are more likely to expect their children to finish school, whereas working-class and underclass families often have lower levels of expectation for their children.

7.1.1.3. From a cultural point of view, schools represent the values of the middle and upper class.

7.1.2. Race

7.1.2.1. Despite the Civil Rights legislation of the 1960s, U.S. society is still highly stratified by race and an individuals race has a direct impact on how much education he or she is likely to achieve.

7.1.2.2. Among 16-24 year-olds, for instance, 5.2 percent of white students drop out of school, whereas 9.3 percent of African-American students are likely to drop out.

7.1.2.3. That race is related to educational outcomes is undeniable, although, given the nature of U.S. society, it is extremely difficult to separate race from class.

7.1.3. Gender

7.1.3.1. Even though women are often rated as being better students than men, in the past they were less likely to attain the same level of education.

7.1.3.2. Today, females are less likely to drop out of school than males, and are more likely to have a higher level of reading proficiency than males.

7.1.3.3. The one area that males outperform females is in mathematics proficiency.

7.2. Coleman Study Responses (1982)

7.2.1. 1st Response

7.2.1.1. Jencks used Coleman's findings to compute the estimated yearly average achievement gain by public and Catholic school students.

7.2.1.2. He found that the differences that do exist between public and Catholic schools are statistically significant, but in terms of significant differences in learning, the results are negligible.

7.2.1.3. Subsequent studies that have compared public and private schools have also found that private schools seem to "do it better," particularly for low-income students.

7.2.2. 2nd Response

7.2.2.1. More than forty years after Coleman's 1966 study, Borman and Dowling found that the data they collected partially confirm both Coleman's 1966 and 1982 studies.

7.2.2.2. They found that where an individual goes to school is often related to her race and socioeconomic background, but the racial and socioeconomic composition of a school has a greater effect on student achievement than an individual's race and class.

7.2.2.3. They also argue that school segregation based on race and socioeconomic status within school interactions dominated by middle-class values are largely responsible for gaps in student achievement.

8. Educational Inequality

8.1. Cultural Deprivation Theories

8.1.1. Middle-Class Culture

8.1.1.1. "Values hard work and initiative, the delay of immediate gratification for future reward, and the importance of schooling as a means to future success."

8.1.2. Poverty Culture

8.1.2.1. "The Culture of poverty eschews delayed gratification for immediate reward, rejects hard work and initiative as a means to success, and does not view schooling as the means to social mobility."

8.2. School-Centered Explanations for Educational Inequality

8.2.1. School Financing

8.2.1.1. Significant differences between affluent suburban and poorer urban districts remain.

8.2.1.2. Public schools are financed through a combination of revenues from local, state, and federal sources.

8.2.1.3. The majority of funds come from property taxes. Since property values are significantly higher in more affluent communities, these communities are able to raise significantly more money for schools through this form of taxation than poorer communities with lower property values.

8.2.2. Between-School Differences: Curriculum and Pedagogic Practices

8.2.2.1. Although there are problems with the research, most researchers agree that its findings support the argument that schools do affect educational outcomes, at times, independent of extra-school factors.

8.2.2.2. Bernstein (1990), examining the situation in England, suggested that schools in working-class neighborhoods are far more likely to have authoritarian teachers and a vocationally centered curriculum. Middle-class communities have less authoritarian teaching practices and focus on humanistic liberal arts. And Upper-class students are more likely to attend elite private schools with more authoritarian teaching practices.

8.2.2.3. "Although Bernstein's work is theoretical and needs further empirical support, especially as it relates to U.S. education, there is a growing research literature that supports the existence of class-based school differences."

8.2.3. Within-School Differences: Curriculum and Ability Grouping

8.2.3.1. At the elementary school level, students are divided into reading groups and separate classes based on teacher recommendations, standardized test scores, and sometimes ascriptive characteristics such as race, class, or gender.

8.2.3.2. At the secondary level. students are divided both by ability and curriculum, with different groups of students often receiving considerably different types of education within the same school.

8.2.3.3. Tracking has a significant effect on educational attainment at both the elementary and secondary levels.

8.2.4. Gender and Schooling

8.2.4.1. Feminist scholarship on schooling has attempted to understand the ways in which the schools limit the educational and life chances of women.

8.2.4.2. It has focused on achievement, on women and school administration, on the history of coeducation, on the relationship between pedagogy and attitudes and knowledge, and other related issues.

8.2.4.3. Feminists agree that schooling often limits the educational opportunities and life chances of women in a number of ways. For example, boys and girls are socialized differently through a variety of school processes.

9. Educational Reform

9.1. School-Based Reforms

9.1.1. Charter Schools

9.1.1.1. Free from many of the regulations applied to traditional public schools, and in return are held accountable for student performance.

9.1.1.2. Paid for with tax dollars (no tuition charges) and must be open to all students in the school district.

9.1.1.3. Are supposed to demonstrate results to the public agencies that review and approve their charter, as well as monitor and audit their progress.

9.1.2. Vouchers

9.1.2.1. Can be used in either religious or secular private schools.

9.1.2.2. Supposed to provide low-income parents the same choices as middle-class parents and lead to increased parental satisfaction.

9.1.2.3. Supposed to provide better learning environments for low-income students and result in higher student achievement.

9.2. Community Reforms

9.2.1. Full Service and Community Schools

9.2.1.1. Focused on meeting students and their families' educational, physical, psychological, and social needs in a coordinated and collaborative fashion between school and community services.

9.2.1.2. Serve as community centers within neighborhoods that are open extended hours to provide services such as adult education, health clinics, and mental health services.

9.2.2. Harlem Children's Zone

9.2.2.1. Canada provides programs for parents in Harlem before their children are born in an attempt to infuse all knowledge that middle-class parents know they should do for their fetuses and infants in a "sensitive way."

9.2.2.2. Expresses hope that all parents will pass along the "Harry Potter values" to their children in order for them to be as academically successful.