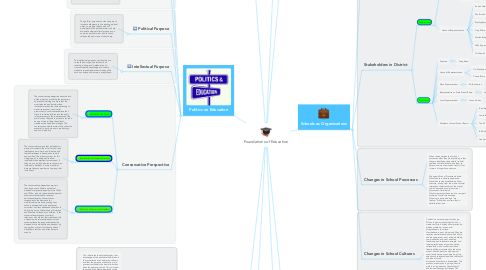

1. Politics on Education

1.1. Social Purpose

1.1.1. The social purposes of schooling are to help solve social problems; to work as one of many institutions, such as the family and the church to ensure social cohesion; and to socialize children into the various roles, behaviors, and values of society.

1.2. Economic Purpose

1.2.1. The economic purposes of schooling are to prepare students for their later occupational roles and to select, train, and allocate individuals into the division of labor.

1.3. Political Purpose

1.3.1. The political purposes of schooling are to inculcate allegiance to the existing political order; to prepare citizens who will participate in this political order; to help assimilate diverse cultural groups into a common political order; and to teach children the basic laws of the society.

1.4. Intellectual Purpose

1.4.1. The intellectual purposes of schooling are to teach basic cognitive skills such as reading, writing, and mathematics; to transmit specific knowledge and to help student acquire higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, evaluation, and synthesis.

1.5. Conservative Perspective

1.5.1. The Role of the School

1.5.1.1. The conservative perspective sees the role of the school as providing the necessary educational training to ensure that the most talented and hard-working individuals receive the tools necessary to maximize economic and social productivity. Conservatives believe that schools socialize children into the adult roles necessary to the maintenance of the social order. They see the school's function as one of transmitting the cultural traditions through what is taught. The conservatives view the role of the school as essential to both economic productivity and social stability.

1.5.2. Explanation of Unequal Education

1.5.2.1. The conservatives argue that individuals or groups of students rise or fall on their own intelligence, hard work, and initiative, and that achievement is based on hard work and sacrifice. The school system, for this vintage point, is designed to allow individuals the opportunity to succeed. If they do not, it may be because they are, as individuals, deficient in some manner or because they are members of a group that is deficient.

1.5.3. Definition of Educational Problems

1.5.3.1. The conservative perspectives argue in their response to liberal and radical demands for greater equality in the 1960s and 1970s, schools systematically lowered academic standards and reduced educational quality. Conservatives responded to the demands for multicultural education by saying that schools watered down the traditional curriculum and thus weakened the school's ability to pass on the heritage of American and Western civilizations to children. In the conservatives response to cultural relativism, schools lost their traditional role of teaching moral standards and values. conservatives also responded about the demands for individuality and freedom by saying that, schools lost their traditional disciplinary function and often became chaotic.

2. Philosophy of Education

2.1. Pragmatism

2.1.1. Generic Notions

2.1.1.1. John Dewey's form of pragmatism--instrumentalism and experimentalism--was founded on the new psychology, behaviorism, and the philosophy of pragmatism. His ideas were influenced by the theory of evolution and by an eighteenth-century optimistic belief in progress. This meant the attainment of a better society through education. The school became an "embryonic community" where children could learn skills both experimentally as well as from books, in addition to traditional information, which could enable them to work cooperatively in a democratic society. His ideas about education proposed that educators start with the needs and interests of the child in the classroom, allow the child to participate in planning his/her course of study, employ project method or group learning, and depend heavily on experiential learning. Dewey's progressive methodology rested on the notion that children were active, organic beings, growing and changing, and thus required a course of study that would reflect their particular stages of development. He believed that the school should reflect the community in order to enable graduating students to assume societal roles and to maintain the democratic way of life. He believed that it could be more perfectly realized through education that would continually reconstruct and reorganize society.

2.1.2. Key Researchers

2.1.2.1. George Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), William James (1842-1910), John Dewey (1859-1952) were the founders of Pragmatism but, Francis Bacon (1561-1626), John Locke (1632-1704), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) had a huge impact.

2.1.3. Goal of Education

2.1.3.1. Dewey fervently believed that philosophy had a responsibility to society and that ides required laboratory testing. He stressed the importance of the school as a place where ideas can be implemented, challenged, and restricted, with the goal of providing students with the knowledge of how to improve the social order. Dewey believed that the schools should balance the needs of society and community on one hand and the needs of the individual on the other. The key to Dewey's vision is his view that the role of the school was to integrate children into not just any type of society, but a democratic one. He did not believe, however, that the school's role was to integrate children into a non-democratic society. Rather, he believed that if schools instilled democratic and cooperative values in children, they would be prepared as adults to transform the social order into a more democratic one. For Dewey, the primary role of education was growth.

2.1.4. Role of Teacher

2.1.4.1. In a progressive setting, the teacher is no longer the authoritarian figure fro which all knowledge flows; rather, the teacher assumes the peripheral position of facilitator. The teacher encourages, offers suggestions, questions, and helps plan and implement courses of study. The teacher also write curriculum and must have a command of several disciplines in order to create and implement curriculum.

2.1.5. Method of Instruction

2.1.6. Curriculum

2.1.6.1. Dewey's notion of a core curriculum, or also called an integrated curriculum, helped progressive educators not be wedded to a fixed curriculum, rather, curriculum changes as the social order changes and as children's interests and needs change. A particular subject matter under investigation by students would yield problems to be solved using math, science, history, reading, writing, music, art, wood or metal working, cooking, and sewing--all the academic and vocational disciplines in an integrated, interconnected way.

3. History of U.S. Education

3.1. Education for All: The Emergence of the Public High School

3.1.1. Prior to 1875, fewer than 25,000 students were enrolled in public high schools. Most adolescents who were engaged in some form of secondary education attended private academies that were either traditional, college preparatory schools, or vocational schools. Between 1880 and 1920, more than two million students attended public high schools, outnumbering those who attended academies, and by 1940, over 6 million students attended public high schools. After a debate lasting over 40 years, a structure for the high school had to be put in place and debates had to be resolved regarding the purpose of secondary education.

3.1.2. One of the greatest changes that has affected high school attendance is that “whereas once it was altogether voluntary, and for this reason quite selective, it is now, at least for those sixteen years old and under, compulsory and unselective. The compulsory school laws grew greatly. In 1890, more than half of the 50 states had compulsory school laws. By 1918, all the states followed the others and began getting the school laws. One of the things that encouraged getting these laws was a court case that happened in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in 1874. This court case paved the way for the school districts’ right to levy taxes to support public high schools.

3.1.3. In examining the evolution of the high school, what becomes immediately apparent is the tension in society over the meaning and purpose of education. Historian Diane Ravitch pointed out four themes that were troubling high school educators.

3.1.3.1. The first was the tension between classical subjects such as Latin and Greek, and modern subjects, such as science, English literature, and foreign languages.

3.1.3.2. The second was the problem of meeting college entrance requirements, since different colleges required different courses of study.

3.1.3.3. The third involved educators who believed that students should study subjects that would prepare them for life, as opposed to traditional academic subjects.

3.1.3.4. The fourth, linked to the other three, was whether all students should pursue the same course of study or whether the course of study should be determined by the interests and abilities of the students.

3.1.4. The Committee of Ten’s recommendations were reinforced in two ways.

3.1.4.1. The first was through the National Education Association’s newly established committee on college entrance requirements, which recommended that all high school students study a core of academic subjects.

3.1.4.2. The second was through the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching’s adoption of the same core courses, which became known as the Carnegie units and which were implemented in high schools throughout the country.

3.1.4.3. In order to address the reality of the school system being not what they thought it would be in the 1890s, and the clarify the purpose of a high school education, a Committee of Ten was formed by the National Education Association, headed by Harvard University President Charles Eliot. The committee issued its report supporting the academic purpose of secondary education and dismissing curricula differentiation. It argued that the purpose of secondary education was the prepare students for “the duties of life”. The committee recommended that modern academic subjects be awarded the same stature as traditional ones. It proposed five model curricula, including classical and modern languages, English, mathematics, history, science, and a liberal arts curriculum. Finally, the committee recommended that all students should be taught in the same manner.

3.1.5. In 1918, the National Education Association’s Commission on the Reorganization of Secondary Schools made its report, which became known as the Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education. These principles opened the door to a curriculum less academically demanding and far more utilitarian than the one proposed by Charles Eliot’s Committee of Ten. The main goals of secondary education were:

3.1.5.1. Health

3.1.5.2. Command of fundamental processes

3.1.5.3. Worthy home-membership

3.1.5.4. Vocation

3.1.5.5. Citizenship

3.1.5.6. Worthy use of leisure

3.1.5.7. Ethical character

3.1.5.8. These main goals are known as the Cardinal Principles. These principles helped to resolve the difficulty of educating students who were not college bound. David Cohen stated, “Americans quickly built a system around the assumption that most students didn’t have what it took to be serious about the great issues of human life, and that even if they had the wit, they had neither the will nor the futures that would support heavy-duty study”.

3.1.6. The final curriculum reform and a logical conclusion to the direction educational reform took during the period preceding the Second World War was the “Education for Life Adjustment” movement. Concerned with the failure of educators to enact any meaningful changed during the Depression years, Prosser proposed a curriculum for the nation’s high schools, which addressed the practical concerns of daily living. Prosser’s ideas were not entirely new; in fact, they could be said to be the logical conclusion of educators who believed, in the final analysis, that not all students were able to master serious academic subject matter.

3.1.7. Prosser and his apostles sought life adjustmentcourses, not just for those at the bottom of the educational ladder but for allhigh school students. Students who once studied chemistry might study “thetesting of detergents; not physics, but how to drive a service car; nothistory, but the operation of the local gas works”. Richard Hofstadter andDavid Cohen are quick to point out that this phase in educational reformexemplifies both the unbridled faith Americans have in education and theambivalent feelings they harbor toward the life of the mind.

4. Schools as Organizations

4.1. Dewey proposed that children learn both individually and in groups. He believed that children should start their mode of inquiry by posing questions about what they want to know. What at first glance to the visitor used to formal pedagogy might appear as chaotic was carefully orchestrated classroom with children going about learning in nontraditionally yet natural ways. Lockstep, rote memorization of traditional schools was replaced with individualized study, problem solving, and the project method.

4.2. Stakeholders in District

4.2.1. Federal Level

4.2.1.1. Senators

4.2.1.1.1. Richard Shelby

4.2.1.1.2. Luther Strange

4.2.1.2. House of Representatives

4.2.1.2.1. Robert Aderholt

4.2.1.2.2. Mo Brooks

4.2.1.2.3. Bradley Byrne

4.2.1.2.4. Gary Palmer

4.2.1.2.5. Martha Roby

4.2.1.2.6. Mike Rogers

4.2.1.2.7. Terri Sewell

4.2.2. Local Level

4.2.2.1. Senators

4.2.2.1.1. Greg Reed

4.2.2.2. House of Representatives

4.2.2.2.1. Tim Wadsworth

4.2.2.2.2. Connie Rowe

4.2.2.3. State Superintendent

4.2.2.3.1. Ed Richardson

4.2.2.4. Representative on State School Board

4.2.2.4.1. Jeffrey Newman

4.2.2.5. Local Superintendent

4.2.2.5.1. Jason Adkins

4.2.2.6. Members of Local School Board

4.2.2.6.1. Brad Ingle

4.2.2.6.2. Jamie Rigsby

4.2.2.6.3. Todd Vick

4.2.2.6.4. Bill Gilbert

4.2.2.6.5. Lee Ann Headrick

4.3. Changes in School Processes

4.3.1. When someone speaks of school processes, what they are explaining is that they are identifying the powerful cultural qualities of schools that make them so potent in terms of emotional recall, if not in terms of cognitive outcomes.

4.3.2. Changes in School Processes include: Schools have a definite population. Schools have clearly defined political structure, arising from the mode of social interaction characteristics of the school, and influenced by numerous minor processes of interaction. Schools represent the nexus of a compact network of social relationships. Schools are pervaded by a “we feeling.”School has a culture that is definitely their own.

4.4. Changes in School Cultures

4.4.1. Conflict is a necessary part of change. Efforts to democratize schools do not create conflicts, but they allow previously hidden problems, issues, and disagreements to surface. New behaviors must be learned. Change requires new relationships and behaviors, the change process must include building communication and trust, enabling leadership and initiative to emerge, and learning techniques of communication, collaboration, and conflict resolution. Team building must extend to the entire school. Shared decision making must consciously work out and give on-going attention to relationships within the rest of the school’s staff. Process and content are interrelated. The process a team uses in going about its work is as important as the content of educational changes it attempts. The substance of a project often depends upon the degree of trust and openness built up within the team and between the team and the school. As these quotes indicate, changing the culture of a school in order to make the school more learner centered requires time, effort, intelligence, and good will.

5. Sociological Perspectives

5.1. Theoretical Perspectives

5.1.1. Functional Theories

5.1.1.1. Functionalist view society as a kind of machine, where one part articulates with another to produce the dynamic energy required to make society work. While Emile Durkheim recognized that education had taken different forms at different times and places, he believed that education, in virtually all societies, was of critical importance in creating moral unity necessary for social cohesion and harmony. For Durkheim, moral values were the foundation of society. Durkheim’s emphasis on values and cohesion set the tone for how present-day functionalists approach the study of education. Functionalists tend to assume that consensus is the normal state in society and that conflict represents a breakdown of shared values. In a highly integrated, well-functioning society, schools socialize students into the appropriate values, and sort and select students according to their abilities. Educational reform, then, from a functional point of view, is supposed to create structures, programs, and curricula that are technically advanced, rational, and encourage social unity. It should be evident that most U.S. educators and educational reformers implicitly base their reform suggestions on functional theories of schooling.

5.1.2. Conflict Theories

5.1.2.1. Not all sociologists of education believe that society is held together by shared values alone. Some sociologists argue that the social order is not based on some collective agreement, but on the ability of domination groups to impose their will on subordinate groups through force, cooptation, and manipulation. In this view, the glue of society is economic, political, cultural, and military power. Ideologies or intellectual justifications created by the powerful are designed to enhance their position by legitimizing inequality and the unequal distribution of material and cultural goods as an inevitable outcome of biology or history. Karl Marx did not write a great deal about education specifically, he is the intellectual founder of the conflict school in the sociology of education. His analytic imagination and moral outrage were sparked by the social conditions found in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century. Marx believed that the class system, which separated owners from workers and workers from the benefits of their own labor, made class struggle inevitable. He believed that, in the end, the proletariat would rise up and overthrow the capitalists, and, in doing so, established a new society where men and women would no longer be alienated from their labor. An early conflict sociologist who took a slightly different theoretical orientation when viewing society was Max Weber. Weber was convinced that power relations between dominant and subordinate groups structured societies, but, Weber believed that class differences alone could not capture the complex ways human beings from hierarchies and belief systems that make these hierarchies seem just and inevitable. Weber also recognized that political and military power could be exercised by the state, without direct reference to the wishes of the dominant classes. Weber made the distinction between the “specialist” and the “cultivated” man. The Weberian approach to studying the relation between school and society has developed into a compelling and informative tradition of sociological research. Researchers in this tradition tend to analyze school organizations and processes from the point of view of status competition and organizational constraints. A growing body of literature suggests that schools pass on to graduates specific social identities that either enhance or hinder their life chances. This advantage has very little to do with what prep. school students learn in school, and a great deal to do with the power of their schools’ reputations for educating members of the upper class. To understand the impact of culture on the lives of individuals and groups, one must understand the meanings that are attributed to cultural experiences by those who participate in them. The conflict perspective, then, offers important insights about the relation between school and society.

5.1.3. Interactional Theories

5.1.3.1. Interactional theories about the relation of school and society are primarily critiques and extensions of the functional and conflict perspectives. The critique arises from the observations that functional and conflict theories are very abstract, and emphasize structure and process at a very general level of analysis. Although this level of analysis helps in understanding education in the “big picture,” macrosociological theories hardly provide an interpretable snapshot of what schools are like on an everyday level. Interactional theories attempt to make the commonplace strange by turning on their heads everyday taken-for-granted behaviors and interactions between students and students, and between students and teachers. By examining the microsociological or the interactional aspects of school life, people are less likely to create theories that are logical and eloquent, but without meaningful content. Basil Bernstein has argued that the structural aspects of the educational system and the interactional aspects of the system reflect each other and must be viewed wholistically. He has examined how speech patterns reflect students’ social class backgrounds and how students from working-class backgrounds are at a disadvantage in the school setting because schools are essentially middle-class organizations.

6. Curriculum & Pedagogy

6.1. Humanist Curriculum

6.1.1. This reflects the idealist philosophy that knowledge of the traditional liberal arts is the cornerstone of an educated citizenry and that the purpose of education is to present to students the best of what has been thought and written. This curriculum focused on the Western heritage as the basis for intellectual development, although some who supported this type of curriculum argue that the liberal arts need not focus exclusively on the Western tradition. This curriculum model dominated nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century U.S. education and was codified in the National Education Association’s Committee of Ten report issued in 1893, “which recommended that all secondary students, regardless of whether they intended to go to college, should be liberally educated and should study English, foreign languages, mathematics, history, and science.”

6.2. Dominant Traditions of Teaching

6.2.1. Mimetic Tradition

6.2.1.1. This tradition is named “mimetic” because it gives a central place to the transmission of factual and procedural knowledge from one person to another, through an essentially imitative process. The procedure for transmitting mimetic knowledge consists of five steps, the series is as follows:

6.2.1.1.1. Step One: Test. Some form of inquiry, either formal or informal, is initiated to discover where the student(s) in question already knows the material or can perform the skill in question.

6.2.1.1.2. Step Two: Present. Finding the student ignorant of what is to be learned, or assuming him or her to be so, the teacher “presents” the material, either discursively—with or without the support of visual aids—or by modeling or demonstrating a skillful performance or some aspect thereof.

6.2.1.1.3. Step Three: Perform/Evaluate. The student, who presumably has been attentive during the presentation, is invited or required to repeat what he or she has just witnessed, read, or heard.

6.2.1.1.4. Step Four (A): (Correct Performance) Reward/Fix. Discovering the performance to be reasonably accurate, the teacher comments favorably on what the student has done and, when deemed necessary, prescribes one or more repetitions in order to fix the material in the student’s repertoire of things know or skills mastered.

6.2.1.1.5. Step Four (B): (Incorrect Performance) Enter Remedial Loop. Discovering the student’s performance to be wrong, the teacher initiates a remedial procedure designed to correct the error in question.

6.2.1.1.6. Step Five: Advance. After the unit of knowledge or skill has been “fixed”, the teacher and student advance to the next unit of “fresh” taught—a qualitative change often of dramatic proportion, a metamorphosis, so to speak. Such changes would include all those traits of character and of personality most highly prized by the society at large.

6.2.2. Transformative Tradition

6.2.2.1. This tradition is one of a transformation of one kind or another in the person being taught a qualitative change, often of dramatic proportion, or a metamorphosis, so to speak. Such changes would include all those traits of character and of personality most highly prized by the society at large. There are three modes to this tradition and they are:

6.2.2.1.1. One: Personal Modeling. OF the many attributes associated with transformative teaching, the most crucial ones seem to concern the teacher as a person. For it is essential to success within that tradition that teachers who are trying to bring about transformative changes personify the very qualities they seek to engender in their students. To the best of their ability they must be living examples of certain virtues or values or attitudes.

6.2.2.1.2. Two: “Soft” Suasion. Among teachers working toward transformative ends, the “showing” and “telling” so central to the mimetic tradition are replace by less emphatic assertions and by an altogether milder form of pedagogical authority. The teaching style is rather more forensic and rhetorical than it is one of proof and demonstration. Often the authority of the teacher is os diminished by the introduction of a questioning mode within this tradition that there occurs a kind of role reversal, almost as though the student were teaching the teacher.

6.2.2.1.3. Three: Use of Narrative. Within the transformative tradition “stories” of one kind or another, which would include parables, myths, and other forms of narrative, play a large role. Why this should be so is not immediately clear, but it becomes so as we consider what is common to the transformations that the schools seek to effect. The common element, it turns out, is their moral nature. Virtues, character traits, interests, attitudes, values—as educational goals all of them fall within the moral realm of the “right” or “proper” or “just”.

7. Equality of Opportunity

7.1. Class

7.1.1. Students in different social classes have different kinds of educational experiences. Education is extremely expensive. The longer a student stays in schools, the more likely he or she needs parental financial support. This situation favors wealthier families. Families from the upper class and the middle class are also more likely to expect their children to finish school, whereas working-class and underclass families often have lower levels of expectation for their children. Teachers have been found to think more highly of middle-class and upper middle-class children than they do of working class and underclass children because working-class and underclass children do not speak middle-class English. In a school that enrolls many middle-class students, there is a high likelihood that more emphasis is pave on high academic achievement than in a school where there are few middle-class children. Study after study shoes that class is related to achievement on reading test and basic skills test. The more elite the college, the more likely the college is to enroll upper-class and upper middle-class students. Social class and level of educational attainment are highly correlated.

7.2. Race

7.2.1. An individual’s race has a direct impact on how much education he or she is likely to achieve. Study after study shows that whites are more likely to finish high school and college rather than African Americans and Hispanics. That race is related to educational outcomes is undeniable, although, given the nature of U.S. society, it is extremely difficult to separate race from class. In a society as segregated as that in the United States, it is not surprising that minority students receive fewer or inferior educational opportunities than white students. Explanations as to why minorities underachieve compared to whites vary. But, at one level, the answer is not terribly complex. Minorities do not receive the same educational opportunities as whites, and their rewards for educational attainment are significantly less.

7.3. Gender

7.3.1. Today, females are less likely to drop out of school than males, and are more likely to have a higher level of reading proficiency than males. The one are that males outperform females is in mathematics proficiency. In the last 20 years, gender differences between men and women, in terms of educational attainment, have been reduced. Liberals argue that these increases demonstrate the success of educational reforms aimed at improving achievement; conservatives argue that the decline in male achievement and attainment is a result of the “feminizing” of the classroom. There are still significant advantages for men when competing for the most prestigious academic prizes.

7.4. Coleman Study from 1982

7.4.1. Response One

7.4.1.1. The first response was that subsequent studies that have compared public and private schools have also found that private schools seem to “do it better,” particularly for low-income students.

7.4.2. Response Two

7.4.2.1. The second response was that where an individual goes to school is often related to her race and socioeconomic background, but the racial and socioeconomic composition of a school has a greater effect on student achievement than an individual’s race and class.

8. Educational Reform

8.1. School-Based Reforms

8.1.1. School-Business Partnership

8.1.1.1. Business leaders became increasingly concerned that the nation’s schools were not producing the kinds of graduates necessary for a revitalization of the U.S. economy. These partnerships have been formed in other cities. Other school-business partnerships include scholarships for poor students to attend college and programs where business “adopt” a school. Over the past decade, however, a group of foundations and entrepreneurs have contributed significantly to educational reform efforts, most often of the neo-liberal variety. School-business partnerships have attracted considerable media attention, but there is little convincing evidence that they have significantly improved schools or that, as a means of reform, school-business partnerships will address the fundamental problems facing U.S. education. Whether or not the new entrepreneurs or the education minded foundations will have more of an effect waits to be seen.

8.1.2. Teacher Education

8.1.2.1. The emergence and development of teacher education as an educational problem was a response to the initial debates concerning the failure of the schools. If the schools were not working properly, then teachers and teaching—perhaps the most important piece in the puzzle—had to be looked at critically. If teachers and teaching were indeed part of the problem, then perhaps the education and training of teachers was a good starting point for analysis. Thus, teacher education, and schools and colleges of education, long the object of critical scrutiny within universities, became the subject of intensive national investigation.

8.2. Two Community Reforms

8.2.1. Full Service and Community Schools

8.2.1.1. A way to attack education inequity is to examine and plan to educate not only the whole child, but also the whole community. Full service schools focus on meeting students’ and their families educational, physical, psychological, and social needs in a coordinated and collaborative fashion between school and community services. In this type of reform, the schools service as a community center within neighborhoods that are open extended hours to provide a multitude of services such as adult education, health clinics, recreation facilities, afterschool programs, mental health services, drug and alcohol programs, job placement and training programs, and tutoring services. This is specifically designed to target and improve at-risk neighborhoods; full-service schools aim to prevent problems, as well as to support them.

8.2.2. Connecting School, Community, and Societal

8.2.2.1. Research conducted over a 20-year period by the Consortium for Chicago School Research at the University of Chicago demonstrates that a combination of school, community, and societal level reforms are necessary to reduce the achievement gap. They demonstrated that these supports are most needed and difficult to implement in the highest poverty schools and that educational reforms must include policies aimed at the amelioration of the effects of poverty. They suggest that the real problem in U.S. education has been, and continues to be, that it works exceptionally well for children from higher socioeconomic backgrounds and exceptionally poorly for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Despite the efforts of school choice and charter school programs to address these inequalities, particularly those in urban schools, the available evidence does not overwhelmingly support the claims of their advocates for a reduction in educational inequality. As the nation moves further into the new millennium, educational equity needs to continue to be on the front burner of educational reform.

9. Educational Inequality

9.1. Cultural Differences Theory

9.1.1. The first type of cultural difference theory is that cultural difference theorists agree that there are cultural and family differences between working-class and nonwhite students, and white middle-class students. Working-class and nonwhite students may indeed arrive at school with different cultural dispositions and without the skills and attitudes required by the schools. This is not due to deficiencies in their home life but rather to being part of an oppressed minority. The key difference in this perspective is that although cultural difference theorists acknowledge the impact of student differences, they do not blame working-class and nonwhite families for educational problems. Rather, they attribute cultural differences to social forces such as poverty, racism, discrimination, and unequal life chances. Researchers, such as John Ogbu, argue that African American children do less in school because they adapt to their oppressed position in the class and caste structure. Ogbu argued that there is a “job ceiling” for African Americans in the United States, as there is for similar caste-like minorities in other countries, and that African American families and schools internalize those values and skill necessary for positions that will not be open to them. Although this is a complex, and at times a hidden, process, the results are lower educational attainment and performance.

9.1.2. The second type of cultural difference theory sees working-class and nonwhite students as resisting the dominant culture of the schools. Research by Willis on working-class boys in England, shows that these students explicitly reject middle-class values and enthusiastically embrace a working-class culture, which eschews the values of schooling. They consciously reject schooling and resist academic success. This resistance results in dropping out of school and into the world of work—that is, the world of the factory floor, which they romanticize as he proper place for men.

9.2. School-Centered Explanations for Educational Inequality

9.2.1. School Financing

9.2.1.1. Public schools are financed through a combination of revenues from local, state, and federal sources. However, the majority of funds come from state and local taxes, with local property taxes a significant source. Property tax is based on the value of property in local communities and therefore is a proportional tax. Since property values are significantly higher in more affluent communities, these communities are able to raise significantly more money for schools through this form of taxation than poorer communities with lower property values. Additionally, since families in more affluent communities have higher incomes, they pay proportionately less of their incomes for their higher school taxes.

9.2.2. School Research

9.2.2.1. On one hand, if student differences are more important than school differences, then teachers cannot be blamed for the lower academic performance of nonwhite and working-class students. On the other hand, if schools’ effects are not significant, then the schools and, more specifically, teachers can do little to make a positive difference. The concern with unequal educational performance of nonwhite and working-class students is at the heart of such inquiry. The finding that within-school differences are as or more significant than between-school differences raised questions about the common-sense argument that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds do poorly simply because they attend inferior schools.

9.2.3. Gender and Schooling

9.2.3.1. Feminist scholarship on schooling has attempted to understand the ways in which the schools limit the educational and life chances of women. The argument that women are more caring and connected, while men more competitive and intellectual, may reproduce sexist stereotypes that historically justified the domestic roles of women. Feminist believe that traditional male and female characteristics are part of the full range of human possibilities, and that schools should socialize both boys and girls to be caring and connected. Despite these differences, feminists agree that schooling often limits the educational opportunities and life chances of women in a number of ways. Schooling often limits the educational opportunities and life chances for women are that the organization of schools reinforces gender roles and gender inequality. For example, the fact that women are far more likely to teach elementary grades and men secondary grades gives the message to children that women teach children and men teach ideas. The fact that men are far more likely to be administrators, despite recent advances in this area, reinforces the view that men hold positions of authority. Given the role that schools play in reproducing gender inequalities, feminists argue that school organization, curriculum, and pedagogic practices need to be changed to address more adequately the needs of females. Educational policy makes have begun to analyze the “boy problem” in order to understand the reasons that boys have begun to lag behind girls.

9.2.4. School Reproduction Inequality

9.2.4.1. There is a significant difference of opinion as to the role of the school in affecting student performance with school-centered explanations stressing the role of school explanation stressing the importance of what students bring to school. The research is conflicting concerning the central hypothesis of functionalism and conflict theory. Some researchers believe that the schools unfairly perpetuate social inequalities and thus confirm conflict theorists’ belief that schools advantage the dominant groups in society. Other researchers believe that there is insufficient evidence to support much of the conflict theory, at least in regard to school processes, and that some of the evidence supports the functionalist view that school selection processes are meritocratic. The relationships between families and schools at the institutional level, and what goes on within schools at the interactional levels, are not isolated from each other but are dialectically intertwined. Students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face significantly different problems in their communities due to factors such as racism, poverty, and other societal and institutional processes. Children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds thus have significantly lower life chances before they enter schools. It is clear that at the intrapsychic level, students from different social class backgrounds leave school with different educational outcomes, both cognitive and noncognitive.