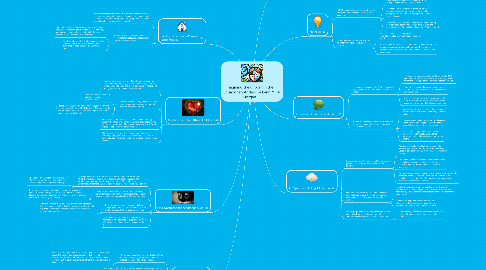

1. Abortion: Self- Vs. Other-Mutilation

1.1. Most of the rural won believed that a fetus is a person from conception. Also meaning that God creates pregnancies and brings babies into being and that at some unspecifiable point during gestation God gives the fetus a soul.

1.2. The women were equally adamant that it is usually wrong to induce abortion but not because abortion is "murder."

1.2.1. They explained that induced abortion is a sin of self-mutilation.

1.2.2. God calls pregnancy into existence, they said, and we are not authorized to interfere with His divine plans. Abortion, then, is not about the mutilation or destruction of a person but about presuming to know God's will.

1.3. Moral justifications for abortion included abandonment by or abuse at the hands of a partner or husband; desperate poverty; hunger, or homelessness; life-threatening contraceptive failure; or the need to protecet a family's honor.

1.4. The rhetoric around abortion in Ecuador emphasizes the centrality of pregnant women's moral integrity and the life circumstances, rather than fetal rights or personification of the unborn.

2. Fetal Death and the Amorphus Auca

2.1. The persistence of faith in the auca is perhaps the best evidence of the inherent ambiguity of the unborn in the rural highlands of Ecuador. The auca has long been a part of Andean ethnography, functioning as a master metaphor for the uncivilized and for several categories of quasi-person.

2.1.1. Elsie Clews Parsons reported in 1945 that "an infant (or anyone) dying unbaptized is called auca...and becomes a night-wandering spirit."

2.2. The infant aucas described to the author in San Gabriel, were frightening and potentially dangerous; they could, by some accounts, turn themselves into ghosts or cannibals.

2.2.1. If there was any agreement about the nature of the auca in San Gabriel, most women agreed that it is the spirit of an aborted fetus, or still-born or murdered baby, which cries pitifully at night in sorrow at not having been baptized.

2.3. There was considerable disagreement about how properly to dispose of an unbaptized fetus or child to prevent it from becoming an auca.

2.3.1. Luz Maria said that the auca can be prevented by baptizing a fetus or neonate even if its dead. But other women insisted that only living babies could receive baptism; the rite could not be posthumously conferred.

2.4. The women of San Gabriel don't agree among themselves who becomes an auca, or under what circumstances, or what powers the auca might possess.

3. Numbering the Babies

3.1. The women the author interviewed in San Gabriel did not share among themselves a common method for enumerating their offspring.

3.1.1. When she asked them how many children they had, some women thought "children" meant pregnancies, in which case all pregnancies--including miscarriages-- figured among a woman's "children." But to others the same word meant children born alive or living children.

3.2. In numbering their offspring, Ecuadorian women have a great deal of latitude in deciding how to classify and represent the differences among living, stillborn, live-born, miscarried, adopted, and deceased children.

3.3. The focus here is not on the baby, the "product," but on the woman's pregnancy and her social responsibility to reproduce.

3.3.1. This is a marked contrast to the U.S. "tentative pregnancy" in which some women postpone an announcement until they have completed the first trimester or until after receiving the results of amniocentesis.

3.4. Birthrates and infant mortality rates are unreliable in Ecuador, in part because the state began to emphasize the importance of registering births and deaths in the mid-1980's.

3.4.1. Underreporting continues to be a problem, in part because relatively few births are attended by professionals.

4. Building Persons is a Woman's Responsibility

4.1. The physical separation of the fetus from the mother at birth is one important step in the process of acquiring personhood, but newborns continue to be dependent on their parents to provide spiritual sustenance and physical strength.

4.2. Fathers, as well as mothers, are held responsible for safeguarding fetuses and newborns in several ways.

4.2.1. They must respond immediately to pregnant women's cravings, abstain from sexual relations for the forty day postpartum period, and remain faithful to their wives (especially while children are at the breast).

4.2.2. Apart from these rather limited responsibilities, however, men absent themselves from the sufferings of birth, miscarriage, and infant death.

5. Abstract

5.1. This article reflects on the uniqueness of U.S. abortion discourse by juxtaposing it against a landscape in which fetuses are generally not considered persons.

5.1.1. Even when the highland women use ultrasound screening, they do not personify or individualize fetuses.

5.1.2. They rarely use the word feto, preferring criatura (creature) or venidero (the one to come).

6. Methods

6.1. In 1988 the author spent two months in the Andean town of San Gabriel, Carchi Province, Ecuador.

6.1.1. She conducted semistructured interviews with thirty mestizo women. These interviews were arranged by her research assistant, Blanca.

6.1.2. They took advantage of the midmorning lull in a woman's workday to ask her, indirectly, about her perceptions of the unborn by asking about her own fertility history

6.1.3. The research was designed to investigate the relationship of between ideals about fetal identity, development. and personhood, and the morality and practice of induced abortion.

6.2. Unlike the United States, Ecuador has no history of public controvery over abortion.

6.2.1. No public initiatives, past or present, have sought to liberalize church or state positions on abortion.

6.2.2. In San Gabriel, the fetus was never regarded separately from the pregnant woman, and women's stories about the events of pregnancy and the status of the unborn were as diverse as their experiences.

7. Ecuador and the Liminal Unborn

7.1. There are many reasons why North Americans might assume that Latin Americans respect the unborn.

7.1.1. The region has been dominated by Catholicism for 500 years, and the Vatican has become an increasingly ardent proponent of fetal personhood over the past twenty years.

7.1.2. Loyal Latin American Catholics are sometimes heard to say that they will bear "as many children as God will send.

7.1.3. It will be a mistake, however, to conclude on the basis of these stereotypes that Latin Americans subscribe to the notion that fetuses are persons.

7.2. In the rural highlands of northern Ecuador, the unborn are imagined as liminal, unripe, and unfinished creatures.

7.2.1. Nascent persons are brought into being slowly, through processes rife with uncertainty and moral ambiguity.

7.2.2. These unknown, unknowable criaturas may teeter on the cusp of personhood for months before being fully welcomed into a human community.

7.2.3. In Ecuador, social practices reinforce and perpetuate fetal liminality, insuring that personhood will not be easily attributed to the unborn.

8. An Open Secret: Illegal Abortion

8.1. Un secreto a voces (an open secret) is how many people in Ecuador describe the availability of abortion

8.1.1. Abortion is officially illegal but nonetheless widely available. Estimates of abortion rates are unreliable in Ecuador, as elsewhere in Latin America, for at least two reasons.

8.1.2. First, most estimates are based on numbers of women hospitalized with complications resulting from a combination of both spontaneous and induced abortions.

8.1.3. Second, hospital-based figures can capture only those women with access to health services, thus excluding much of the rural population, and do not reflect the numbers of women whose abortions are successful and safe.

8.2. Ecuadorian law allows abortion under only two circumstances: to save the life of a woman, or when pregancy is of the rape of a mentally ill woman.

8.2.1. The fact that abortion providers and clients are infrequently prosecuted in Ecuador suggests that the practice of abortion is tolerated by a state apparatus that protects the unborn only at the level of rhetoric.

8.2.2. Ecuadorians might continue to abortion both illegal and widely available as long as the issue remains below the surface of public discourse.

8.3. The law purports to value and protect fetal life and personhood, but lack of enforcement of antiabortion laws belies the state's commitment.

8.3.1. Fetuses may be rhetorical persons by Ecuadorian law, but in social practice there are no fetal persons.