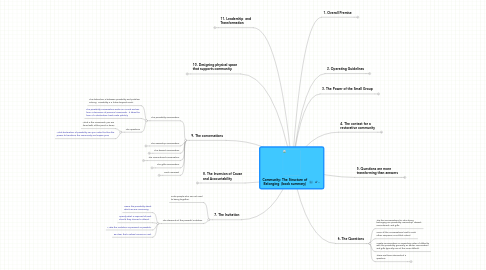

1. 7. The Invitation

1.1. Invite people who are not used to being together.

1.2. The elements of the powerful invitation

1.2.1. Name the possibility about which we are convening.

1.2.2. Specify what is required of each should they choose to attend.

1.2.3. Make the invitation as personal as possible.

1.2.4. Be clear that a refusal carries no cost.

2. 8. The Inversion of Cause and Accountability

2.1. We reclaim our citizenship when we invert what is cause and what is effect.

2.2. Citizens create leaders, children create parents, and audience creates the performance. This inversion may not be the whole truth, but it is useful.

2.3. The inversion creates conditions where we can shift from

2.3.1. A place of fear and fault to one of gifts, generosity, and abundance;

2.3.2. A bet on law and oversight to one on social fabric and chosen accountability;

2.3.3. The corporation and systems as central, to associational life as central;

2.3.4. A focus on leaders to a focus on citizens;

2.3.5. Problems to possiblity.

3. 11. Leadership and Transformation

3.1. Leadership that engages citizens is a capacity that exists in all human beings. It is infinitely and universally available.

3.2. Transformation occurs when leaders focus on the structure of how we gather and the context in which the gatherings take place.

3.3. Leadership is convening and held to three tasks;

3.3.1. Shift the context within which people gather.

3.3.2. Name the debate through powerful questions.

3.3.3. Listen rather than advocate, defend, or provide answers.

4. 9. The conversations

4.1. The possibility conversation

4.1.1. The distinction is between possibility and problem solving. Possibility is a future beyond reach.

4.1.2. The possibility conversation works on us and evolves from a discussion of personal crossroads. It takes the form of a declaration, best made publicly.

4.1.3. The questions

4.1.3.1. What is the crossroads you are faced with at this point in time?

4.1.3.2. What declaration of possibility can you make that has the power to transform the community and inspire you?

4.2. The ownership conversation

4.2.1. It asks citizens to act as is if they are creating what exists in the world.

4.2.2. The distinction is between ownership and blame.

4.2.3. The questions

4.2.3.1. For an event or project

4.2.3.1.1. How valuable an experience (or project, or community) do you plan for this to be?

4.2.3.1.2. How much risk are you willing to take?

4.2.3.1.3. How participative do you plan to be?

4.2.3.1.4. To what extent are you invested in the well-being of the whole?

4.2.3.2. The all-purpose ownership question

4.2.3.2.1. What have I done to contibute to the very thing I complain about or want to change?

4.2.3.3. The questions that can complete our story and remove its limiting quality

4.2.3.3.1. What is the story about this community or organization that you hear yourself most often telling? The one you are wedded to and maybe even take your identity from?

4.2.3.3.2. What are the payoffs you receive from holding on to this story?

4.2.3.3.3. What is your attachment to this story costing you?

4.3. The dissent conversation

4.3.1. The dissent conversation creates an opening for commitment.

4.3.2. When dissent is expressed, just listen. Don't solve it, defend against it, or explain anything.

4.3.3. The primary distinction is between dissent and lip services.

4.3.4. A second distinction is between dissent and denial, rebellion, or resignation.

4.3.5. The questions

4.3.5.1. What doubts and reservations do you have?

4.3.5.2. What is the no or refusal that you keep postponing?

4.3.5.3. What have you said yes to that you no longer really mean?

4.3.5.4. What is a commitment or decision that you have changed your mind about?

4.3.5.5. What resentment do you hold that no one knows about?

4.3.5.6. What forgiveness are you withholding?

4.4. The commitment conversation

4.4.1. The commitment conversation is a promise with no expectations of return.

4.4.2. Commitment is distinguished from barter.

4.4.3. The enemy of commitment is lip service, not dissent or opposition.

4.4.4. The commitments that count the most are the ones made to peers, other citizens.

4.4.5. We have to explicitly provide support for citizens to declare that there is no promise they are willing to make at this time.

4.4.6. Refusal to promise does not cost us our membership or seat at the table. We only lose our seat when we do not honor our word.

4.4.7. Commitment embraces two kinds of promises

4.4.7.1. My behavior and actions with others.

4.4.7.2. Results and outcomes that will occur in the world.

4.4.8. The questions

4.4.8.1. What promises am I willing to make?

4.4.8.2. What measures have meaning to me?

4.4.8.3. What price am I willing to pay?

4.4.8.4. What is the cost to others for me to keep my commitments, or to fail in my commitments?

4.4.8.5. What is the promise I'm willing to make that constitutes a risk or major shift for me?

4.4.8.6. What is the promise I am postponing?

4.4.8.7. What is the promise or commitment I am unwilling to make?

4.5. The gifts conversation

4.5.1. The leadership and citizen task is to bring the gifts of those on the margin into the center.

4.5.2. The distinction is between gifts and deficiencies or needs.

4.5.3. We are not defined by deficiencies or what is missing We are defined by our gifts and what is present.

4.5.4. We choose our destiny when we have the courage to acknowledge our own gifts and choose to bring them into the world.

4.5.5. A gift is not a gift until it is offered.

4.5.6. The questions

4.5.6.1. What is the gift you still hold in exile?

4.5.6.2. What is something about you that no one knows?

4.5.6.3. What gratitude do you hold that has gone unexpressed?

4.5.6.4. What have others done in this room done, in this gathering, that has touched you?

4.6. Final comment

4.6.1. The important thing about these questions is that they name the agenda that creates space for an alternative future. The power is in the asking, not in the answers.

5. 10. Designing physical space that supports community.

5.1. Physical space is more decisive in creating community than we realize.

5.2. Most meeting spaces are designed for control, negotiation, and persuasion.

5.3. We always have a choice about how we rearrange and occupy whatever room we are handed.

5.4. Community is built when we sit in circles, when there are windows and the walls have signs of life, when every voice can be equally heard and amplified, when we all are one level--and the chairs have wheels and swivel.

5.5. When we have the opportunity to design new space, we need the following:

5.5.1. Reception areas that tell us we are in the right place and are welcome.

5.5.2. Hallway's wide enough for intimate seating and casual contact.

5.5.3. Eating spaces refresh us and encourage relatedness.

5.5.4. Meeting rooms designed with nature, art, conviviality, and citizen-to-citizen interaction in mind.

5.5.5. Large community spaces that have the qualities of communal intimacy.

5.6. The design process itself needs to be an example of the future we are intending to create.

5.7. Authentic citizen and employee engagement is as important as good design expertise.

6. 6. The Questions

6.1. The five conversations for structuring belonging are possibility, ownership, dissent, commitment, and gifts.

6.2. Since all the conversations lead to each other, sequence is not that critical.

6.3. Create conversations in ascending order of difficulty, with the possibility generally an earlier conversation and gifts typically one of the more difficult.

6.4. There are three elements of a question:

6.4.1. The distinction that underlies the question.

6.4.2. An admonition against advice and help in favor of curiousity.

6.4.3. The question itself, stated precisely.