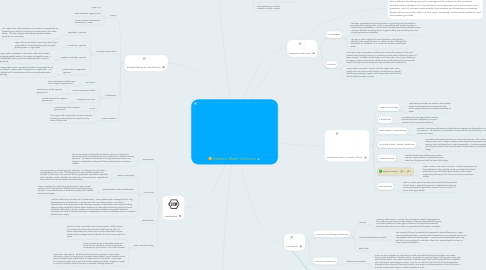

1. Obstacles

1.1. Government

1.1.1. The Government is reluctant to recognize Makoko as a legitimate community as demonstrated by its 2013 destruction of several housing structures. We assume that based on the governments actions, any long-term prospective solutions will face political barriers to entry in Makoko

1.2. Community

1.2.1. Makoko community

1.2.1.1. The community is not welcoming to outsiders. According to the Guardian's photographer, John Vidal, "[i]t is dangerous to go in without guides, and volatile" (Vidal, 2005). This makes it hard to get reliable information about the water situation, hard to develop, test and role out new solutions, regardless of the potential to increase access to potable water.

1.2.2. Existing water solution stakeholders

1.2.2.1. There is resistance to expanding government or new, private solutions from those who currently deliver the existing working solutions. These stakeholders include formal water truck lobbies and informal gangs.

1.2.3. Makoko suffers from a severe lack of infrastructure. Thus potable water is brought it from long distances by way of boreholes or Mairuwa who sell clean drinking water. The lack of insfrastructure, including proper water drainage, piping for clean water, clean water plumbing systems, water sanitization plants, waste disposal and intermittent electricity supply will cause substantial difficulty for any non-mobile source of water sanitation as any water sanitation innovation will need to be self-sustaining or independent in order to reliably produce a consistent potable water supply.

1.3. Infrastructure

1.4. Black market for water

1.4.1. Due to the lack of available clean drinking water, a black market for trading water has arisen whereby locals travel up north to obtain clean water from bore holes or other clean water sources which is then packaged and sold back to the local community for a profit

1.4.2. There are several communal water points but locals have to paddle up to 3km to get there and then pay up to 3p for a 10L bucket of water

1.4.3. Asymmetric information - the black market leads to a problem of asymmetric information. Given the high price of privately traded water, there is incentive to sell more accessible lower quality water to capture some of the profit. As the buyer isn't aware of quality and source of the water, absent any ability of vendor to signal or verify the quality of water the buyer is exposed to being ripped off

2. Opportunities

2.1. LifeStraw

2.1.1. Hyper-mobile innovations like the LifeStraw could be used in Makoko for relatively micro-level water purification. LifeStraw has been deployed in Western Kenya to success, with hundreds of schools provided access to clean drinking water.

2.2. Bicycle Water Purifier

2.2.1. Developed by Japanese company Nippon Basic, the Bicycle water purification system filters water, powered by the rotation of the bike pedals. If this technology could be slightly re-engineered to be powered by the movement of a boat, mobile filtration methods could be developed, custom to Makoko

2.3. The Watercone

2.3.1. Solar powered water filtration to potentially be used atop floating communities

3. The Problem

3.1. Built on water but lack of access to clean and safe drinking water

3.2. Considered an "illegal settlement" so severe lack of government investment results in city needing to be self sufficient: 70 % of the families in Makoko lack public water

3.3. Most water is provided to citizens through private small entrepreneurs who dig up groundwater and sell it on different locations around Makoko. On average, a family in Makoko spends 31 USD per month on ground water

3.4. Health implications resulting from unclean water in Makoko are vast; typhoid, malaria, diarrhea, and cholera are widespread

3.5. Life expectancy of Makoko residents is under 40 years

4. Stakeholders & Institutions

4.1. NGOs

4.1.1. Water Aid

4.1.2. Water Initiatives Nigeria (WIN)

4.1.3. African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF)

4.2. Municipal Government

4.2.1. Regulatory Agencies

4.2.1.1. The Lagos State Water Regulatory Commission is responsible for protecting the interest of investors and consumers in the water sector, it is also charged with settling disputes between produces and consumers

4.2.2. Monitoring Agencies

4.2.2.1. Lagos State Drug Quality Assurance Laboratory is responsible for monitoring the quality of piped drinking water in Lagos State

4.2.3. Supply and Quality Agencies

4.2.3.1. The Lagos Water Corporation is the public water utility tasked with supplying potable water in the Lagos Metropolitan area. it is also tasked with ensuring that the supplied water conforms with standards

4.2.4. Waste Water Management Agencies

4.2.4.1. The Lagos State Waste Management Office is responsible for all issues related to waste water management in Lagos state. It is also tasked with the development of eco-friendly waste water technology

4.3. Multilaterals

4.3.1. World Bank

4.3.1.1. The World Bank provides loans to the Nigerian government

4.3.2. African Development Bank

4.3.2.1. Provide loans to the Nigerian government

4.3.3. European Union (EU)

4.3.3.1. Provide loans to the Nigerian government

4.3.4. USAID

4.3.4.1. Provide loans to the Nigerian government

4.4. Private Investors

4.4.1. The Lagos Water Corporation has been actively soliciting private partners for investment into water infrastructure

5. The Makoko Floating School is designed to adopt to the resident communities’ lifestyle; it is build by local materials such as timber and bamboo, and it utilises sustainable techniques and features including applications for solar cells on the roof, rainwater catchment systems and composting toilets.

6. Solutions

6.1. Current Working Solutions

6.1.1. Mairuwa

6.1.1.1. Meaning 'water-owner' in Hausa (one of Nigeria's national languages) are the most common informal water solution. They are individuals who queue and collect water from public taps and deliver to individual households and areas where there is no water. No guarantee that the water is potable.

6.1.2. Household boreholes and wells

6.1.2.1. The majority of formal households (as opposed to slum settlements) in Lagos rely on private boreholes. Manually drilled boreholes are unregulated and are not a guaranteed source of drinking water - many provide contaminated water (e.g. with salt, micro-organisms). In addition, there is an environmental risk from so many individual boreholes.

6.1.3. Public taps

6.2. Future Solutions

6.2.1. Floating Communities

6.2.1.1. Given a small ecosystem of newly-built and self-sustainable floating communities, rain waiter harvest and purification methods could be employed en masse to support that greater community with drinking water. Rain water purification methods would need to be parsed out into a detailed plan with proper technologies in place. Thus far, NLE Studios (the studio that has designed the Floating School schematic) has only alluded to rain water purification systems in their architecture but with noactionable evidence of this capability thus far.

7. Solutions from Across Africa

7.1. Water Pouches

7.1.1. Polyethylene pouches are used to store potable water and transported over distances to be sold in easily mobile and individual quantities of water

7.2. LifeStraw

7.2.1. As mentioned in the opportunities section, LifeStraw has been deployed in Kenya to success by the company's reporting

7.3. Rainwater Harvesting

7.3.1. Rainwater harvesting methods are collect natural rainwater and storage the contents in a reservoir. The reservoir is connected to a pump which the community can use to access clean water

7.4. Gravity Flow Water Systems

7.4.1. In locations that where the terrain is more mountainous or hill, a stream or body of water from a higher location can be tapped and pumped into a reservoir which is physically at a lower topography. This allows gravity to naturally push water into a reservoir which is connected to a pump within a village

7.5. Hand pump

7.5.1. Installed pumps atop subterraneous water sources, communities can individually pump water from the ground with this basic technology

7.6. Rope Pump

7.6.1. Used in Burkina Faso, this is similar to a water hand pump, but the processes is automated by a lever connected to a wheel, which when spun will shuttle groundwater to the surface, augmenting efficiency of the volume of water pumped per minute

7.7. Boreholes

7.7.1. Used in Malawi, when the earth surface is difficult to penetrate or fresh water is deep below ground, a hydraulic borehole rig can be employed to dig holes in excess of 100m in order to source fresh groundwater

8. Lessons Learned

8.1. Successes

8.1.1. The water privatization that already exists in Lagos has proven successful in providing safe drinking water. This is in accordance with studies focusing on infrastructure privatization in Africa overall. Studies show that privatizations have numerous benefits, including efficiency gains, stable and reduced prices, and reduced government subsidies.

8.1.2. The gap in water supply that currently exists is partly met by informal water supply vendors, so called Mairuwa. Although this alternative has limitations, it is a mean for families to get access water.

8.2. Failure

8.2.1. The Lagos Water Corporation’s solutions to increase the supply of clean and reliable water through focusing on improving current water infrastructure has not been enough. The water demand gap in 2014 was 300 MGD. Major challenges to improve Lagos’ current water infrastructure include lack of skilled manpower, limited funding, low level of productivity, and low levels of efficiency.

8.2.2. Lagos Water Corporation aims to fund the Lagos State Water Supply Plan 2010-2020 partly through private funding; despite fundraising campaigns, Lagos Water Corporation has not been able to attract enough investors.