1. What Does the Unemployment Rate Tell Us About an Economy's Health?

1.1. How the Government Measures Unemployment

1.1.1. Every month, the BLS reports the total number of people who were unemployed for the previous month. To arrive at this figure, the BLS does not attempt to count every job seeker in the country. Instead, it conducts a sample survey each month. By examining a small but representative sample of the population, the BLS can gauge how many people in the entire population are unemployed.

1.2. Types of Unemployment

1.2.1. Frictional unemployment

1.2.1.1. a type of unemployment that results when workers are seeking their first job or have left one job and are seeking another

1.2.2. Structural Unemployment

1.2.2.1. a type of unemployment that results when the demand for certain skills declines, often because of changes in technology or increased foreign competition; under such conditions, workers may need retraining to find new jobs

1.2.3. Seasonal unemployment

1.2.3.1. a type of unemployment that results when businesses shut down or slow down for part of the year, often because of weather

1.2.4. Cyclical unemployment

1.2.4.1. a type of unemployment that results from a period of decline in the business cycle; unemployment caused by a contraction

1.3. Full Employment and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

1.3.1. When an economy is healthy and growing, it experiences little cyclical unemployment. But there will always be some frictional, seasonal, and structural unemployment. Some people will always be out of work, even in an economy with full employment. At that point, all of the economy’s available labor resources are being used efficiently.

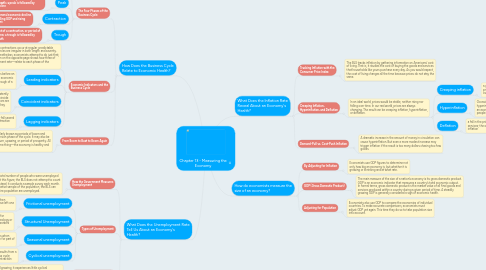

2. How Does the Business Cycle Relate to Economic Health?

2.1. The Four Phases of the Business Cycle

2.1.1. Expansion

2.1.1.1. a period of economic growth

2.1.2. Peak

2.1.2.1. the highest point of an expansion, or period of economic growth; a peak is followed by economic decline

2.1.3. Contraction

2.1.3.1. a period of general economic decline marked by falling GDP and rising unemployment

2.1.4. Trough

2.1.4.1. the lowest point of a contraction, or period of economic decline; a trough is followed by economic growth

2.2. Economic Indicators and the Business Cycle

2.2.1. The term business cycle implies that expansions and contractions occur at regular, predictable intervals. But in fact, the opposite is true. Business cycles are irregular in both length and severity. This makes peaks and troughs difficult to predict. Nonetheless, economists attempt to do just that, using a variety of economic indicators. The illustration on the opposite page shows how three of these indicators—GDP, inflation rate, and unemployment rate—relate to each phase of the business cycle.

2.2.2. Leading indicators

2.2.2.1. Measures that consistently rise or fall several months before an expansion or a contraction begins are called leading economic indicators. They are used to forecast the peak and trough of a business cycle, although not very precisely.

2.2.3. Coincident indicators

2.2.3.1. Coincident economic indicators are measures that consistently rise or fall along with expansions or contractions. They coincide with the phases of the business cycle. Coincident indicators are most helpful in tracking expansions and contractions as they happen.

2.2.4. Lagging indicators

2.2.4.1. measures that consistently rise or fall several months after an expansion or contraction begins

2.3. From Boom to Bust to Boom Again

2.3.1. Business cycles are popularly known as periods of boom and bust. A boom is the expansion phase of the cycle. It may also be known as a recovery, upturn, upswing, or period of prosperity. All these terms mean the same thing—the economy is healthy and growing.

3. How do economists measure the size of an economy?

3.1. By Adjusting for Inflation

3.1.1. Economists use GDP figures to determine not only how big an economy is, but whether it is growing or shrinking and at what rate.

3.2. GDP (Gross Domestic Product)

3.2.1. The main measure of the size of a nation’s economy is its gross domestic product. GDP is an economic indicator that measures a country’s total economic output. In formal terms, gross domestic product is the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country during a given period of time. A steadily growing GDP is generally considered a sign of economic health.

3.3. Adjusting for Population

3.3.1. Economists also use GDP to compare the economies of individual countries. To make accurate comparisons, economists must adjust GDP yet again. This time they do so to take population size into account.

4. What Does the Inflation Rate Reveal About an Economy's Health?

4.1. Tracking Inflation with the Consumer Price Index

4.1.1. The BLS tracks inflation by gathering information on Americans’ cost of living. That is, it studies the cost of buying the goods and services that households like yours purchase every day. As you would expect, the cost of living changes all the time because prices do not stay the same.

4.2. Creeping Inflation, Hyperinflation, and Deflation

4.2.1. In an ideal world, prices would be stable, neither rising nor falling over time. In our real world, prices are always changing. The result can be creeping inflation, hyperinflation, or deflation.

4.2.1.1. Creeping inflation

4.2.1.1.1. a gradual, steady rise in the price of goods and services over time

4.2.1.2. Hyperinflation

4.2.1.2.1. Occasionally inflation goes into overdrive. The result is hyperinflation. Runaway inflation creates extreme uncertainty in an economy. Nobody can predict how high prices will go, and people lose confidence in their currency as a store of value.

4.2.1.3. Deflation

4.2.1.3.1. a fall in the price of goods and services; the opposite of inflation

4.3. Demand-Pull vs. Cost-Push Inflation

4.3.1. A dramatic increase in the amount of money in circulation can cause hyperinflation. But even a more modest increase may trigger inflation if the result is too many dollars chasing too few goods.