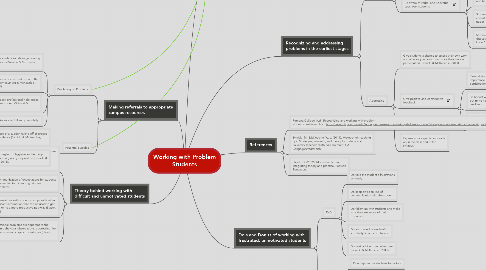

1. Theory behind working with difficult and unmotivated students

1.1. The instructor should aim to convince students that the problems are not based on lack of ability but rather it is a temporary problem that can be overcome with more effective strategies, more effort, or dealing with stress more effectively (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

1.2. Communication of expectations for students is essential to minimizing student problems.

1.3. Conversations with students can provide other important information that can be used to get them on to a more productive pathway (Stipek, 2002).

1.4. Even if motivational problems are apparent to the instructor from behavioral observations, addressing the behavior requires various types of strategies (Stipek, 2002).

2. Making referrals to appropriate campus resources

2.1. Psychological Problems

2.1.1. Get the student to talk to you during office hours (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

2.1.2. Express concern and listen to the student (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

2.1.3. Have the student seek professional help; make the first step for the student (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

2.1.4. Make sure to follow up regularly.

2.2. Potential Suicides

2.2.1. Be aware of a sudden falling off of grades or attendance (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

2.2.2. Be aware of neglect of hygiene and lethargic movement and a gloomy disposition (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3. Appropriate intervention strategies for different styles of behavior

3.1. Aggressive, challenging students

3.1.1. Delve more deeply into the logic behind the facts and principles (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.1.2. Model what it means to be a critical thinker in the face of challenges to your ideas (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.2. Students who are under-prepared for the course or struggling

3.2.1. Point towards supplemental resources (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.2.2. Prepare tutorials on common deficits (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.2.3. Develop sample questions and put alternative materials on reserve in the library (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.2.4. Develop a classroom FAQ page and discussion board as a way to provide help to struggling students (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.2.5. Use pre-assessments to identify difficulties. Have students complete self-assessments and try to offer suggestions (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.2.5.1. Review missed classes, study habits, and note taking skills.

3.2.6. Referral to campus resources such as learning support centers, or writing centers (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.3. Attention seekers and students who dominate discussion

3.3.1. Suggest you want to get everyone's ideas for multiple perspectives (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.3.2. Ask the classroom for suggestions on what can be done to give all students a chance to participate (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.3.3. Have a few students act as process observers, audiotape or videotape class for playback (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.3.4. Meet with the attention seeker outside of class to discuss their behavior in class (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.4. Inattentive students

3.4.1. Determine if problem is content driven or with the students (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.4.2. Use group activities in order to get inattentive students to participate in activities (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.4.3. Rotate seats and move inattentive students to the front (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.4.4. During classroom discussion ask for feedback on what aspects were most interesting (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.4.5. Meet with inattentive students outside of class to express concern about their lack of attentiveness (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.5. The flatterer and con man or woman

3.5.1. Start with an assumption of honesty (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.5.2. Do not change the rules for one person if you are not willing to change for everyone - no favoritism (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.6. Students with excuses

3.6.1. Integrate the use of rough drafts as a check point on larger assignments (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.6.2. Communicate late policy penalties in the syllabus (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.6.3. Offer bonus points for papers turned in early (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.6.4. Have a good offense rather that a good defense (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7. Angry students

3.7.1. Get to know the student and what angers them (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.2. Include angry student in a group feedback session (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.3. Let the student know you see them as an individual and are interested in listening to them and responding constructively (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.4. Listen carefully and respectfully (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.5. Recognize the student's feelings (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.5.1. Do not rely on your authority as the instructor to make your point; try to resolve and clarify the issue (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.5.2. Present the issue to the class for discussion and other viewpoints (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.5.3. Admit that you may have been wrong. Be honest with the students and advise that you will research the topic and present the findings during the next class period (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.7.6. If students are angry about grades and feedback offer to have another instructor assess the assignment (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.8. Discouraged, ready-to-give-up students

3.8.1. Have older students share their experiences and frustrations of adapting to a new level of education (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.9. Students with emotional reactions to sensitive topics

3.9.1. Acknowledge the sensitivity of the topic (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.9.2. Explain why the topic is relevant to the course outcomes (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.9.3. Let students know that they should listen and respect the viewpoints of other students (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.9.4. Have students write a short essay advocating an alternate viewpoint in order to get them to open their minds to other viewpoints (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.9.5. Allow time for classroom discussion (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.10. Unprepared students

3.10.1. Announce quizzes and make them routine (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.10.2. Clearly communicate expectations in the syllabus (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

3.10.3. Use effective feedback in classroom discussions and written assignments.

4. Recognizing and addressing problems in the earliest stages

4.1. Recognizing

4.1.1. Give quizzes and tests early in the term to help students identify and diagnose their difficulties (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

4.1.2. Be aware of verbal and nonverbal cues from students

4.1.2.1. "I am a terrible writer."

4.1.2.2. "My professor requires use to use the writing center."

4.1.2.3. "I just want to turn this paper in and be done with it."

4.1.2.4. Student has had multiple consultations on the same paper.

4.1.2.5. Student is unresponsive to classroom discussion or answers with "I don't know."

4.2. Addressing

4.2.1. Give students a chance to assess their own work and offer suggestions to improve their work or participation (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

4.2.2. Give positive and constructive feedback

4.2.2.1. Remind students of the importance of classroom participation.

4.2.2.2. Be honest with students in your written feedback but try to keep it balanced and include positive feedback.

4.2.2.3. For students who seem unsure or do not have an answer refer them back to the text to further clarify the author's point.

4.2.3. Express your expectations early on in the class and in the syllabus.

5. Do's and Don'ts of working with frustrated, unmotivated students

5.1. Do's

5.1.1. Do take the student's frustrations seriously.

5.1.2. Do keep an open line of communication with the student.

5.1.3. Do follow up with students and make sure they are aware of their resources.

5.1.4. Do acknowledge student's sensitivity to sensitive topics.

5.1.5. Do seek advice from colleagues (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).

5.2. Don'ts

5.2.1. Don't ignore the students behaviors.

5.2.2. Don't assume you know the reasoning behind the student's behavior.

5.2.3. Don't duck controversy (Svinicki & McKeachie, 2011).