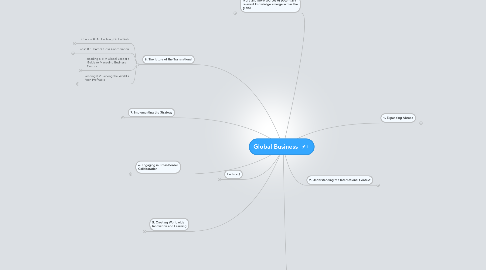

1. More and more sources of potentially relevant knowledge emerge across the globe

1.1. Companies must establish a presence in an increasing number of locations to access new knowledge

1.1.1. McKinsey spread their firm to 42 locations --> New knowledge

2. 4. Developing a Transnational Organization

2.1. Chapter 4: Managing Integration, Responsiveness and Flexibility

2.1.1. Implementing a three-plonged strategic objective (worldwide learning, national responsiveness and global efficiency) would be difficult under any circumstances

2.1.1.1. Going international multiplies a company's organizational complexiity

2.1.2. John Stepfords Research

2.1.2.1. Stages model of international organizational structure, shows how companies expand globally.

2.1.2.2. 2 variables

2.1.2.2.1. Foreign product diversity

2.1.2.2.2. Foreign sales as a % of total sales

2.1.2.3. Companies start with an international division

2.1.2.3.1. Either expand into other markets without product diversity

2.1.2.3.2. Or with a lot of product diversity

2.1.2.4. End up in global matrix

2.1.2.4.1. Report to 2 superiors, double reporting

2.1.2.5. Double chain of command

2.1.2.5.1. Matrix amplifies differences in perspectives and interest

2.1.3. Beyond structure: "Fit"

2.1.3.1. Early stages

2.1.3.1.1. MNE's typically managed their overseas operations through an international division

2.1.3.2. Global matrix

2.1.3.2.1. Frontline managers report simultaneously to different organizational groups

2.1.3.3. Global matrix failed:

2.1.3.3.1. Increasing complexity by forcing all issues through the double chain of command

2.1.4. Building organizational capability

2.1.4.1. Basic problem underlying a company's search for a structural fit was that if focused on only one organizational variable

2.1.4.1.1. Formal structure

2.1.4.2. A more suitable tool:

2.1.4.2.1. Administrative Heritage

2.1.5. Administrative Heritage

2.1.5.1. Company's history and its embedded management culture influences its organization and its ability and willingness to change --> HISTORY MATTERS

2.1.5.1.1. Is shaped by past internal structures and management bias as well as current external task demands

2.1.5.1.2. Influenced by values, norms and practices of its management

2.1.5.1.3. Administrative heritage is one of the greatest assets providing underlying source of its core competencies and liability

2.1.5.1.4. No such thing as a zero-based organization

2.1.5.1.5. Different types

2.1.6. Transnational Organization

2.1.6.1. Limits to the administrative heritage

2.1.6.1.1. MNE's trying to match capabilities of their competitor and protect own ones

2.1.6.2. 3 Core competencies which will distinguish transnational organization from heritage

2.1.6.2.1. Multidimensional Perspectives: Sense and analyse diver and conflicting opportunities

2.1.6.2.2. Distributed, interdependent capabilities: Response to diverse opportunities and demand.

2.1.6.2.3. Flexible integrative process: Resolve the diversity of interest and integrate the dispersed assets and resources

2.1.7. Building a Transnational Organization: Anatomy, Physiology and Psychology

2.1.7.1. What exactly is involved in building a Transnational Organization

2.1.7.1.1. Organizational Anatomy

2.1.7.1.2. Physiology

2.1.7.1.3. Psychology

2.1.8. Managing the process of change

2.1.8.1. Traditional Change in :

2.1.8.1.1. 1. Formal structure (anatomy)

2.1.8.1.2. 2. Interpersonal relationships (physiologies)

2.1.8.1.3. 3. Individual attitudes (psychologies)

2.1.8.1.4. Disadvantage: Forcing change

2.1.8.2. Emerging change processes

2.1.8.2.1. 1. Individuals attitude (psychologies)

2.1.8.2.2. 2. Interpersonal relationships (physiologies)

2.1.8.2.3. 3. Formal structure (anatomy)

2.1.8.2.4. Disadvantage: In times of crisis radical restructuring might be better.

2.1.9. The Transnational Organization in Transition

2.1.9.1. Wide preach transnational organizational trends

2.1.9.1.1. Dissatisfaction with formal matrix structre

2.1.9.1.2. Redefinition of key organization dimensions - global customer dimension

2.1.9.1.3. Changing the functional management role

2.2. Reading 4-1: Organizing for an Emerging World

2.2.1. Becoming Global --> High complexity!

2.2.1.1. Article gives ideas on organizational design

2.2.2. Rethinking Boudaries

2.2.2.1. Shift in boundaries

2.2.2.1.1. Emerging markets change boundaries between activities

2.2.2.2. A complex calculus:

2.2.2.2.1. No company's restructuring should be viewed as a blueprint

2.2.2.3. Process Pointers

2.2.2.3.1. Executives evaluating the structure of their companies

2.2.2.3.2. Valuable ideas:

2.2.3. Lightening the Corporate Heart

2.2.3.1. Corporate centres have been slimming down over the past decaded

2.2.3.2. Companies have found locations other than corporate HQ for centres of excellence.

2.2.4. Coordinating Communication

2.2.4.1. Having the right structures and processes to enable growth and reduce complexity is triumph itself

2.2.4.1.1. May falter without right linkages

2.2.4.2. Managers should focus their communications on contacts that really matter to their job

2.2.4.3. Taking stock;

2.2.4.3.1. Understanding the number and value of the communications that managers participate in.

2.2.4.3.2. Variety of tools are available to help

2.2.4.4. Strengthening the right connections

2.2.4.4.1. Once people understand the number and nature of their connections and communications

2.3. Reading 4-2: Have you Restructured for Global Business?

2.3.1. Emerging markets grow explosively

2.3.1.1. Multinational raced to develop new strategies

2.3.2. Pressures on multinational structures seems likely to intensify

2.3.2.1. Businesses are increasingly seeking not just suppliers and raw materials, but also customers in emerging markets.

2.3.3. Multinational corporations are scouting for new products and services in developing countries

2.3.4. Same time:

2.3.4.1. Nature of innovation is becoming gloabl

2.3.4.1.1. technological advances

2.3.5. Emerging of a new structure!

2.3.5.1. T-shaped country organization

2.3.5.1.1. Localize customer-facing operations even as it distributes back-end activities across countries

2.3.6. For companies that are keen to tap into the full potenital of emerging markets, none of these structures are performing as well as they once did

2.3.7. Falling into the Gap:

2.3.7.1. Tectonic forces are together opening a set of gaps between multinational companies' ambitions and achievements in emerging markets

2.3.7.1.1. Passion gap

2.3.7.1.2. Value-proposition gap

2.3.7.1.3. Product line gap

2.4. Reading 4-3: Matrix Management: Not a Structure, a Frame of Mind.

2.4.1. Top-level managers are losing control over their companies

2.4.1.1. Companies are organizationally incapable of carrying out the sophisticated strategies they have developed

2.4.2. Strategic trap

2.4.2.1. Was to implement simple, static solutions to complex and dynamic problems.

2.4.2.2. End result was often a consultant's siren song promising to simplify or at least minimize complexity

2.4.2.2.1. Success if stick to their knitting

2.4.2.2.2. Solution was mostly too simple for complex companies

2.4.3. Organizational trap conclusion:

2.4.3.1. The best response to increasingly complex strategic requirements was increasingly complex organizational structures

2.4.3.1.1. Matrix structure became fashionable

2.4.3.1.2. Parallel reporting led to conflict and confusion

2.4.4. Building an Organization

2.4.4.1. Problem:

2.4.4.1.1. Companies remain caught in the structural complexity trap that paralyzes their ability to respond quickly

2.4.4.2. Coming back to anatomy, phsiology, and psychology

2.4.4.3. Building the organization rather than simply installing new structures

2.4.5. Building a shared vision

2.4.5.1. Clear and consistent vision:

2.4.5.1.1. 1. Clarity

2.4.5.1.2. 2. Continuity

2.4.5.1.3. 3. Consistency

2.4.6. Developing Human Resources

2.4.6.1. Focus on finance overshadows the task of developing capable managers

2.4.6.1.1. 1. Recruitment and selection

2.4.6.1.2. 2. Training and Development

2.4.6.1.3. 3. Career-path management

3. 5. Creating Worldwide Innovation and Learning

3.1. Chapter 5: Exploiting Cross-Border Knowledge Management

3.1.1. Traditional Innovation: Central and Local Models

3.1.1.1. Traditionally MNEs' innovative capabilities were dominated by one of two classic processes

3.1.1.2. Centre- for global innovation model: New opportunity was sensed in the home country

3.1.1.2.1. Centralized resources and capabilities of the parent company were brought in to create the new product or process, usually in the main R&D Centre

3.1.1.3. Local-for-local:

3.1.1.3.1. Risk:

3.1.1.3.2. Fit more easily into the multinational strategic model

3.1.1.3.3. Multinational companies are often masters at managing local innovations

3.1.1.3.4. To get rid of these problems this has been succesful

3.1.1.3.5. Most MNEs have tried to develop element of both models of innovation, but usually one dominates

3.1.2. Transnational Innovation: Locally leveraged, globally linked

3.1.2.1. The traditional models that shaped cross-border innovation have evolved into new processes: Transnational innovation models:

3.1.2.1.1. Locally leveraged innovation

3.1.2.1.2. Globally linked

3.1.3. Making Transnational processes feasible

3.1.3.1. Building a portfolio of innovative processes to drive worldwide learning requires that companies overcome two related but different problems:

3.1.3.1.1. Avoid various pitfalls associated with each process

3.1.3.1.2. Find ways to overcome the organizational contradictions among them as they try to manage all the sources of innovation simultaneously

3.1.3.2. The drive to reduce organizational and strategic complexity made these assumptions extremely widespread for MNEs

3.1.3.2.1. An often-implicit assumption

3.1.3.2.2. An concious/non consious assumption

3.1.3.2.3. Assumption

3.1.3.3. Companies that are most successful in developing transnational innovations challenge these assumptions

3.1.3.3.1. Systematically differentiate tasks and responsibilities

3.1.3.3.2. Build and manage interdependence among different unity of companies

3.1.3.3.3. Corporate managers search for complex mechanism to coordinate and coopt the differentiated and interdependent organizational units into sharing a vision of the company's strategic tasks.

3.1.4. From Symmetry to Differentiation

3.1.4.1. Product coordination groups formed at corporate centre and soon encompassed all businesses

3.1.4.1.1. Different businesses faced different demands for integration and responsiveness

3.1.5. From Dependence to Independence to Interdependence

3.1.5.1. The emerging strategic demands make organizational models based on such simple inter-unit dependence or independence inappropriate

3.1.5.1.1. They must build the interdependent relationships that re at the heart of the transnational, integrated-network organization

3.1.5.2. For an effective interdependent organization to exist

3.1.5.2.1. The company must develop the interdependent configuration of dispersed and specialized resources.

3.1.5.2.2. The innovative transnational organization must build inter unit integration mechanisms to ensure that task interdependencies lead to the benefits of synergy rather than paralysis of conflict

3.1.6. Form Simple control to Flexible coordination

3.1.6.1. The simplifying assumptions of organizational symmetry and dependence allowed the management porcesses in many companies to be dominated by simple controlls

3.1.6.2. Challenge assumptions

3.1.6.2.1. Found out that tehy also needed to adapt their management process

3.1.6.3. As MNEs began exploring transnational innovation opportunities simultaneously, they became more diverse and more interdependent

3.1.6.3.1. Explosion in the number of issues that had to be linked, reconciled and integrated

3.1.6.3.2. cost of coordinating are high, coordinating capabilities are always linked.

3.1.6.4. Three flows are the lifeblood of any organization

3.1.6.4.1. Flow of goods

3.1.6.4.2. Flow of resources

3.1.6.4.3. Flow of valuable information and knowledge

3.2. Case 5-3: Mckinsey & Company: Managing Knowledge and Learning

3.2.1. Haha grapje kankeraap

3.3. Reading 5-1: Building Effective R&D Capabilities Abroas

3.3.1. More and more companies in technologically intensive industries have abandoned the traditional approach to R&D, as this approach will no longer suffice. 2 Reasons

3.3.1.1. Companies competing around the world must move new products from development to market at an ever more rapid pace

3.3.1.1.1. Companies must build R&D networks that excel at tapping new centers of knowledge and at commercializing products in foreign markets with the speed required to remain competitive

3.3.2. Adopting a Global Approach to R&D

3.3.2.1. 1. Creating a technology steering committee: Build a team that will lead the initiative

3.3.2.1.1. Small teams of senior managers

3.3.2.1.2. Members include head of major existing R&D sites

3.3.2.2. 2. Categorizing new R&D Sites: R&D Sites have one of two objectives

3.3.2.2.1. Home-base-augmenting site

3.3.2.2.2. Home-base-exploiting site

3.3.2.3. 3. Choosing a location for the site

3.3.2.3.1. For home-base augmenting sites

3.3.2.3.2. For home-base-exploiting sites

3.3.3. Establishing a new R&D Facility

3.3.3.1. In both types of new facilities companies must use the same three-stage process

3.3.3.1.1. Selecting best laboratory leader:

3.3.3.1.2. Determining the optimal size for the new R&D Site:

3.3.3.1.3. Supervising the start-up period:

3.3.3.2. Compare MCK now and in the beginning

3.4. Reading 5-3: How to Collaborative Advantage

3.4.1. Multinational corporations could compete scucessfully by exploiting scale and scope economies

3.4.1.1. No longer profitable

3.4.2. Multinationals compete head-to-head with a handful of other giants

3.4.3. New economies of scope are based on the ability of business units, subsidiaries and functional departments within company to collaborate successfully by sharing knowledge and jointly developing new products and services

3.4.4. Value creation from Interunit collaboration

3.4.4.1. Interunit collaboration is difficult to achieve and understand

3.4.4.2. Not collaborate across units for collaboration's sake only

3.4.4.2.1. Reap economic benefits

3.4.4.3. Five major benefit categories

3.4.4.3.1. Cost savings through transfer of best practices

3.4.4.3.2. Better decision making as a result of advice obained from colleagues in other subsidiaries

3.4.4.3.3. Increased revenue through the sharing of expertise and products among subsidiaries

3.4.4.3.4. innovation through the combination and crosspollination of ideas

3.4.4.3.5. Enhanced capacity for collective actin that involves dispersed units

3.4.5. Four barriers to interunit collaboration

3.4.5.1. Companies often erect barriers that prevent individuals from engaging in collaborative activities that they might otherwise have undertaken

3.4.5.2. First task: Identify the barriers and their causes. 4 barriers

3.4.5.2.1. First barrier:

3.4.5.2.2. Second barrier

3.4.5.2.3. Third barrier

3.4.5.2.4. Fourth barrier

3.4.6. Management levers to promote

4. 6. Engaging in Cross-Border Collaboration

4.1. Chapter 6. Managing across Corporate Boundaries

4.1.1. Need to pursue multiple sources of competitive advantage simultaneously

4.1.1.1. Building not only interdependent and integrated network organization but also collaborative relationships with other firms

4.1.1.1.1. Change in strategic perspective

4.1.2. Change in strategic perspective was triggered by:

4.1.2.1. Rising R&D Costs

4.1.2.2. Shortened Product life cycles

4.1.2.3. Growing barriers to market entry

4.1.2.4. Increasing needs for global-scale economies

4.1.2.5. Expanding importance of global standards

4.1.3. Response:

4.1.3.1. Many shifted their strategic focus away from an all-encompassing obsession with premating competition to a broader view of building competitive advantage through selective, often simultaneous reliance on both collaboration and competitions

4.1.4. Simultaneously consideratin of both value creation and value appropriation

4.1.4.1. Partnerships with customers

4.1.4.1.1. Leveraging their own competitiveness and innovative capabilities

4.1.5. Most visible manifestation of this growing role of collaboration strategies appears in the phenomena "strategic alliances"

4.1.5.1. Why Strategic Alliances?

4.1.5.1.1. Strategic alliances: A variety to interfere cooperation agreements, ranging from shared research to joint venture.

4.1.5.1.2. Traditional joint ventures were formed between a senior multinational headqueartered in a developed country and a junior local partner in a less-developed country

4.1.6. Technology exchange:

4.1.6.1. Technology transfer of R&D collaboration is a major objective of many strategic alliances

4.1.6.1.1. Why?

4.1.6.1.2. Result:

4.1.6.1.3. Future:

4.1.7. Global Competition

4.1.7.1. A widespread perception has emerged:

4.1.7.1.1. Global competitive battles will be fought between teams of players, aligned in strategic partnerships

4.1.7.2. Industries with dominant worldwide market leader

4.1.7.2.1. Joint ventures, strategic alliance and network allow coalitions of smaller partner to compete more effectively against common enemy

4.1.8. Industry convergence

4.1.8.1. High-tech industries are converging

4.1.8.1.1. Seems to creat a competitive traffic jam

4.1.8.2. Alliances

4.1.8.2.1. Shaping competition by reducing competitive intensity

4.1.9. Economies of scale and reduction of risks

4.1.9.1. Several ways that strategic alliances allow firms to reap the benefits of scale economies or learning

4.1.9.1.1. Advantage for smaller firms

4.1.10. Forming alliances as an alternative for merging:

4.1.10.1. Industry sectors in which regulator's limit the extent of cross-border mergers and acquisitions

4.1.10.1.1. Companies create alliances (Best alternative)

4.1.10.2. Alliances

4.1.10.2.1. Full-scale global integration if restrictions on foreign ownership are lifted

4.1.11. The Risk & Cost of collaboration

4.1.11.1. Triad Power

4.1.11.1.1. Emphasized he needs to develop significant positions in 3 key markets (US, EU & JAP) as a prerequisite for competing in global industries

4.1.11.2. Stick-to-your-knitting

4.1.11.2.1. Urged managers to disaggregate the value chain and focus on their investments etc. on only those tasks in which the company has a competitive advantage

4.1.11.3. Risk of competitive collaboration

4.1.11.3.1. Strategic alliances involve partners who are future competitors outside the specific scope of the cooperative venture

4.1.11.3.2. Collaborative venture might be used by one or both partners to develop a competitive edge over the other

4.1.11.3.3. Carefully constructed strategic alliances can become problematic

4.1.11.4. The cost of strategic and organizational complexity

4.1.11.4.1. Cooperation is difficult to attain even under the best circumstances

4.1.11.4.2. Strongest forces facilitating such behaviour

4.1.12. Building and managing a collaborative venture

4.1.12.1. Alliances are neither conventional organizations with fully internalized activities nor well-specified transaction relationships

4.1.12.1.1. Combine both elements

4.1.12.2. Collaborative ventures present significant management challenges

4.1.12.2.1. Strategic and environmental disparities lack of common experience and perception base difficulties in interfere communication conflict of interests and priorities

4.1.12.2.2. Big differences between establishing alliances and making them work

4.1.12.3. Challenge in two parts

4.1.12.3.1. 1. Reflecting the pre-alliance tasks of analysis

4.1.12.3.2. 2. Decision making and the post-alliance tasks of coordination

4.1.13. Building cooperative ventures

4.1.13.1. The quality of the pre-alliances processes of partner selection and negotiating influences the clarity and reciprocity of mutual expectations from alliances

4.1.13.2. Three aspects of the pre-alliance process:

4.1.13.2.1. 1. Partner selection

4.1.13.2.2. 2. Escalating commitment

4.1.13.2.3. 3. Alliance Scope

4.1.14. Managing the boundaries

4.1.14.1. Many different ways on how to structure the boundary of an alliance and manage the interface between this boundary

4.1.14.1.1. Two extremes:

4.1.14.2. Choice among alternative boundary strucutures depends on the scope of the alliance

4.1.14.2.1. Alliance tasks are extensive functional interdependencies

4.1.14.2.2. Alliance between two companies with the objective of marketing

4.1.14.3. Managing knowledge flows

4.1.14.3.1. process of collaboration creates flows of information across the boundaries of the participating companies

4.1.14.4. Providing strategic direction: The governance structure

4.1.14.4.1. Equality can prevent companies from creating an effective structure

4.1.14.4.2. Integrative rather than distributive equality: Different tasks

4.1.15. Comment:

4.1.15.1. Alliances seem easy and good to handle while sometimes they aren't!

4.2. Case 6-3: Eli Lily in India

4.2.1. Lily was re-evaluating the joint-venture with Ranbaxy

4.2.2. The global pharmaceutical industry in the 90s

4.2.2.1. Had come about through both forward integratino from the manufacturer of organaic chemcials and the backward integration from druggist supply housees

4.2.2.2. Rapid growth

4.2.2.3. Patents were the essential mean by which firm protected it proprietary knowledge

4.2.2.3.1. Safety provided by patents allowed firms to price their products

4.2.3. The indian Pharmaceutical industry

4.2.3.1. Devloping countries such as India alhtough large by population were characeterized by low/capital gross income

4.2.3.1.1. Healthcare expenditures accounted for a very small share

4.2.4. Eli Lily and Company

4.2.4.1. Founded by Cln. Eli Lilly in 1876

4.2.4.2. One of the largest pharamceutical companies in US

4.2.4.3. Systematic expansions

4.2.4.3.1. Significant move to global market

4.2.5. Ranbaxy laboratories

4.2.5.1. 1960s family business

4.2.5.1.1. Visionary management

4.2.5.2. Core competencies

4.2.5.2.1. Checmical synthesis capability

4.2.5.2.2. Outsourcing bulk drugs

4.2.6. The Lilly Ranbaxy JV

4.2.6.1. Ranxabxy approached Lilly in 1992 to investigate the possiblity of supplying certain active ingredients or sourcing of intermediate product to Lilly

4.2.6.2. Lilly wanted joint venture focusing on marketing

4.2.6.3. 1992: Joint venture

4.2.6.4. The start up

4.2.6.4.1. 1993: getting the venture up and running with office space and an employee base

4.2.6.4.2. Within a year the venture began gaining trust and respect of doctors, due to strong values adhered to by Lilly

4.2.6.4.3. Much of the success is attributed to strong and cohesive working relationships

4.2.6.4.4. The mid-term organizational change

4.2.7. The new world, 2001:

4.2.7.1. Pharmaceutical industry continued to grow

4.2.7.2. Lilly developed "Prozac"

4.2.7.2.1. running out of patent in 2001, what to do now?

4.2.8. Evaluation Strategic options

4.2.8.1. Forming a new joint venture?

4.2.8.2. Buying out the part of one company in joint venture.

4.3. Reading 6-1: The Design and Management of International Joint Ventures

4.3.1. An international joint venture is a company that is owned by two or more firms of different nationality

4.3.2. Formed from a starting basis or may be the result of several established companies deciding to merge existing divisions

4.3.3. Joint ventures have moved from being a way to enter foreign markets of peripheral interest to become a part of the mainstream of corporate activities

4.3.4. The popularity of alliances has continued despite their reputation for being difficult to manage

4.3.5. Why companies create international joint ventures?

4.3.5.1. International Joint Ventures can be used to achieve basic purposes

4.3.5.1.1. Strengthening the existing business

4.3.5.1.2. Achieving economies of scale

4.3.5.1.3. Raw Materials and component supply

4.3.5.1.4. R&D

4.3.5.1.5. Marketing and Distribution

4.3.5.1.6. Divisional merges

4.3.5.1.7. Acquiring technology in core business

4.3.5.1.8. Reducing financial risk

4.3.6. Requirements for international joint ventures

4.3.6.1. 1, Test the strategic logic

4.3.6.2. 2. Partnership and fit

4.3.6.3. 3. Shape and Design

4.3.6.4. 4. Doing the deal

4.3.6.5. 5. Making the venture work

4.3.7. Joint ventures are increasingly important part of the strategy of many firms. They are however sometimes difficult to design and manage well, on part because some organizations treat the as true joint ventures.

4.4. Reading 6-2: How to Manage Alliances Better than One at the Time

4.4.1. Companies are myopic (bijziend) when they go about forming strategic partnerships

4.4.1.1. Systemizing analysis process should produce more gain less pain.

4.4.2. Leading question

4.4.2.1. How can companies form strategic alliances that create value on a standalone basis and at the alliance portfolio level?

4.4.2.1.1. Use an alliance business case framework that takes into account the costs and benefits on both levels

4.4.2.1.2. Empower an individual or department to oversee alliance formation decisions

4.4.2.1.3. Implement an integrated and codified decision process

4.4.3. The formation of the new alliance may even be an overall vale-destroying move.

4.4.4. Existing alliance portfolios have more positive effect on companies' stock prices than alliances with little or no synergy.

4.4.5. Pitfalls of alliance portfolio expansion

4.4.5.1. Alilance portfolios often result from a sedimentary accumulation process

4.4.5.1.1. Engage in multiple alliances over time and all these partnerships accumulate haphazardly

4.4.6. Making alliances fit

4.4.6.1. Having a corporate level department that coordinates all alliances-related activity across a company's multiple units

4.4.7. Holistic cost-benefit analyse

4.4.7.1. Only move into an alliance if it creates value

5. 7. Implementing the Strategy

5.1. Chapter 7: Building Multidimensional Capabilities

5.1.1. 21th century MNE is markedly different from its ancestors

5.1.1.1. Has been transformed by an environment with conflicting forces

5.1.2. Creation of environmentally complexity, diversity and change

5.1.2.1. Globalization of markets

5.1.2.2. Acceleration of product and technology life cycles

5.1.2.3. Assertion of national governments' demands

5.1.2.4. Intensification of global competition

5.1.3. Need to develop multiple strategic assets

5.1.4. Able to sense and interpret complex and dynamic environmental changes

5.1.5. Global Business Management:

5.1.5.1. The challenge of developing global efficiency and competitiveness requires that management capture the various scale and scope economies available to the MNE, as well as capitalize on the potential competitive advantages inherent in its worldwide market positioning.

5.1.5.2. Three core tasks and responsibilities

5.1.5.2.1. Global business Strategist

5.1.5.2.2. Architect of worldwide asset and resource configuration

5.1.5.2.3. Cross-border coordination

5.1.6. Worldwide Functional Management

5.1.6.1. Diffuse innovations and transfer knowledge on a world wide base: Three responsibilities

5.1.6.1.1. 1. Worldwide scanner of specialized information and intelligence

5.1.6.1.2. 2. Cross-pollinator of best practice

5.1.6.1.3. 3. Champion of transnational innovation

5.1.7. Geographic Subsidiary Management

5.1.7.1. Enormous strategic complexity

5.1.7.2. Country managers:

5.1.7.2.1. Role is becoming more difficult, because MNE's move toward global business units

5.1.7.3. Three tasks of country managers:

5.1.7.3.1. Bicultural interpreter:

5.1.7.3.2. National defender and advocate

5.1.7.3.3. Frontline implementer of corporate strategy

5.1.8. Top Level Corporate Management

5.1.8.1. Senior executives have to integrate and provide direction and have to break with many of the norms of the company

5.1.8.2. Add value

5.1.8.2.1. liberating the organization below

5.1.8.3. Constant balancing and integrating divergent influences in the ongoing management process

5.1.8.3.1. Long-term viability and achieving short-term results

5.1.8.4. Providing direction and purpose:

5.1.8.4.1. They have to create a common vision

5.1.8.4.2. 3 Characteristics of an energizing strategic vision:

5.1.8.5. Leveraging corporate performance

5.1.8.5.1. Achieve results in the short term to remain viable among competitors

5.1.8.5.2. Abandon old notions of control that often saw their role primarily as monitoring

5.1.8.5.3. Top-down interference has to be replaced by corporate-lever support

5.1.8.6. Ensuring Continual Renewal

5.1.8.6.1. Successful strategies can become elevated to the status of unquestioned wisdom and effective organizational processes become institutionalized as embedded routines

5.1.8.6.2. Top management prevent from occuring

5.2. Case 7-4: Managing a Global Team: Greg James at Sun Microsystems Inc.

5.2.1. Greg James global manager

5.2.2. HS Holding

5.2.2.1. James scanned his inbox, reliving the events that had plunged him into predicament

5.2.3. James' Journey

5.2.3.1. Holding's system was up and running, the face-to-face meetings with his team had uncovered deeper, more complex interpersonal issues.

5.2.3.2. Sun launched the Open Work Program that allowed people to work from anywhere, anytime any place.

5.2.3.3. Nick Elliott --> Primary contact for account

5.2.3.4. Praveen felt insulted by Nick

5.2.3.5. Miscommunication between US, India and the UAE about what the queue should do

5.2.4. Greg James:

5.2.4.1. Early career had been promising

5.2.4.2. Sun had set up a suitability for employees who wanted to participate in open work

5.2.4.3. Managers filled out a category assessment survey that polled work patterns, activates, resoureces, work style and background

5.2.4.4. The data collection process also looked at the amount of interaction with other team members and internal or external customers, how frequently he or she worked from home and whether the employee was a self-starter.

5.2.4.5. Sun had established an organizational system such as training for managers and employees working in global teams, resources form home based employees and workshpos on open work.

5.2.5. James' team

5.2.5.1. Recruitment:

5.2.5.1.1. 45 persons

5.2.5.1.2. 7 in France

5.2.5.1.3. 16 in India

5.2.5.1.4. 11 in UAE

5.2.5.1.5. 11 IN US

5.2.5.2. James found open work environment beneficial

5.2.5.3. Time zone and work:

5.2.5.3.1. James had ket in touch with his direct report many times during the week

5.2.5.3.2. Weekly conference call with his entire team of 45

5.2.5.3.3. Picked time zone which was most convenient for every one

5.2.5.3.4. Indian team felt left out

5.2.5.3.5. James felt each country was frustrated

5.2.5.3.6. France compensation mismatched

5.2.5.3.7. US complained having less vacation

5.2.5.3.8. UAE did not have sufficeint face to face contact with james

5.2.5.4. What to do?

5.2.5.4.1. Increase face-to-face

5.2.5.4.2. Decrease face-to-face

5.3. Reading 7-2: Tap your Subsidiaries for Global Reach

5.3.1. How could a fairy-tale story turn so quickly in a nightmare? Structure and management process that impeded company's ability to capitalize on it's technological assets and its worldwide market position

5.3.2. The company lacked:

5.3.2.1. The ability to sense changes in market needs and industry structure occuring away from home

5.3.2.2. The resources to analyse data and develop strategic responses to competitive challenged that were emerging worldwide

5.3.2.3. The managerial initiative, motivation and capability in its overseas operations to reason imaginatively to diverse and fast-changing operating environments.

5.3.3. United Nation model & HQ syndrome

5.3.3.1. Our study covered 9 core competencies in three industries and a dozen secondary companies from a diverse industrial spectrum

5.3.3.2. The UN model of multinational management:

5.3.3.2.1. Thus it is common to see managers express subsidiary roles and responsibilities

5.3.3.2.2. When national units are opreationally self-sufficient and strategically independent

5.3.3.3. The HQ hierarchy syndrome, grows out of and is reinforced by the UN model assumption.

5.4. Reading 7-3: The Collaborative Imperative

5.4.1. Organizations face an increasingly complex and unpredictable competitive landscape and one that is filled with new aggressive competitors

5.4.2. In the years ahead volatility and uncertainty will tyrannize markets and companies will need leaders who are highly adaptive, continuous learners able to lead diverse groups across functional disciplines

5.4.3. Getting to the root of collaboration challenges

5.4.3.1. Organizations became flatter and more matrixes

5.4.3.2. Huge advantages

5.4.3.2.1. New innovations

5.4.3.2.2. Increased sharing of information

5.4.3.2.3. Better capacity

5.4.3.3. Huge challenges

5.4.3.3.1. Decisions take longer

5.4.3.3.2. Costs of bringing people together can add to a company's bottom line

5.4.4. Collaborating in the matrix

5.4.4.1. Collaboration is not the same as teamwork

5.4.4.2. Group employees by both function and product employees operate with less direct supervision from local leaders

5.4.4.3. Bad collaboration:

5.4.4.3.1. wasting time and money

5.4.5. Building collaborative culture

5.4.5.1. Senior executives have both the responsibility and the power to encourage and foster a culture of collaboration

5.4.5.2. Key collaborative competencies:

5.4.5.2.1. Leadership and organizational structure matter in building a collaborative culture, but organizations still need right people with right skills to lead collaboration initiatives toward the desired outcome.

5.4.5.2.2. Six key capabilities

5.4.5.2.3. Cultivating collaborative leaders

5.4.5.2.4. Colaborating more, collaborating better

6. 8. The future of the Transnational

6.1. Chapter 8: An Evolving Global Role

6.1.1. New millennium offered exiting prospects of continued growth and prosperity

6.1.2. Reputation of MNEs were shaky or tattered

6.1.2.1. Not good press of large MNEs

6.1.3. The Growing Discontent

6.1.3.1. Growing distrust for MNEs

6.1.3.1.1. Groundswell against globalization

6.1.3.2. Unfair to poorer countries

6.1.4. The Challenge facing MNEs

6.1.4.1. Growing view

6.1.4.1.1. time to radically rethink and approach that relied heavily on government-funded aid program

6.1.4.2. Successes in India & China

6.1.4.2.1. Unleashing the power of their market economies

6.1.4.3. MNE control much of necessary resources that would be necessary to have a lasting impact on developing countries

6.1.5. Responding to Developing World Needs: Four MNE Postures

6.1.5.1. Exploitive

6.1.5.1.1. Shareholders

6.1.5.1.2. Customers

6.1.5.1.3. Employees

6.1.5.1.4. Local communities

6.1.5.1.5. Government

6.1.5.1.6. NGOs

6.1.5.1.7. Additional info

6.1.5.2. Transactional

6.1.5.2.1. Shareholders

6.1.5.2.2. Customers

6.1.5.2.3. Employees

6.1.5.2.4. Local communities

6.1.5.2.5. Government

6.1.5.2.6. NGOs

6.1.5.2.7. Additional info

6.1.5.3. Responsive

6.1.5.3.1. Shareholders

6.1.5.3.2. Customers

6.1.5.3.3. Employees

6.1.5.3.4. Local communities

6.1.5.3.5. Government

6.1.5.3.6. NGOs

6.1.5.3.7. Additional info

6.1.5.4. Transformative

6.1.5.4.1. Shareholders

6.1.5.4.2. Customers

6.1.5.4.3. Employees

6.1.5.4.4. Local communities

6.1.5.4.5. Government

6.1.5.4.6. NGOs

6.1.5.4.7. Additional info

6.2. Case 8-1: Barrick Gold Coorperation

6.2.1. How to solve the problem where to expand and what to do with the workers

6.2.2. Background on Tanzania

6.2.2.1. Tanzania was a developing country in east-Africa

6.2.2.2. Highest level of unemployment

6.2.2.3. High corruption and weak legal system

6.2.2.4. Institutions more transparant and accountable

6.2.2.5. 1961: Independence

6.2.2.6. 1980: Economic stagnation and social problems

6.2.2.7. 1990s: Privitize economy

6.2.3. Lake Victoria background

6.2.3.1. Lake victoria zone in Tanzania:

6.2.3.1.1. The lake victoria zone considered of the three regions of Mwanza, Mara and Kagera and was one of the most densely populated regions

6.2.3.1.2. People were engaged in fishing, agricultural farming and keeping cattle

6.2.3.1.3. Most fertile for farming

6.2.3.2. Mining in Tanzania

6.2.3.2.1. Gold mining started in colonial are in 1894

6.2.3.2.2. Collapse in Ujamaa in 1990s

6.2.3.2.3. 1995: Exploration of mining activities

6.2.3.2.4. 1999: Barrick invested Tanzania

6.2.3.2.5. Productivity of gold has been growing

6.2.4. Barrick Gold Corp. in Tanzania:

6.2.4.1. As a gold producer on the world stage, Barrick used advanced exploration technological systems for its mining development projects

6.2.4.2. Mission, vision and value:

6.2.4.2.1. Given the questionable reputation of some global mining corporations with respect to sustainable development projects in developing societies

6.2.4.2.2. Core vision and values were to continue finding, acquiring, developing and producing quality reserves in a safe, profitable and socially responsible manner.

6.2.4.3. Building Social Development Initiatives

6.2.4.3.1. Barrick was committed to making a positive difference in the communities where it operated

6.2.4.3.2. The company focused on responsible behaviour as its duty

6.2.4.3.3. Several communities felt they were isolated when it came to the social issues that concerned them

6.2.4.4. Creating a Corporate Responsive Agenda

6.2.4.4.1. Barrick developed a responsive initiative to deal with the company's challenges in its international business activities abroad.

6.3. Reading 8-1: A Global Leader's Guide to Managing Business Conduct

6.3.1. Managers working outside their home environment often find that their companies' norms are inconsistent with practices followed by other businesses in the area

6.3.2. Should companies automatically default their home-country practices?

6.3.2.1. NO

6.3.2.2. A strong consesus on basic standards of conduct that companies should follow worldwide

6.3.2.3. An approach that is guided by global standards

6.3.3. Identify your conduct gaps

6.3.3.1. Governments or employees are calling for a change in corporate behaviour

6.3.4. The Conduct Gap

6.3.4.1. Emplees tend to agree on what comapnies should do

6.3.4.1.1. Employers don't live up to those standards

6.3.4.2. Gap between should and do

6.3.4.2.1. Three patterns which are widespread

6.3.5. Develop Data Driven Tools

6.3.5.1. With governments, the public and employees expressing a desire to see better coroparte behaviour

6.3.5.1.1. How can companies improve?

6.3.6. The Global Business Standards Project:

6.3.6.1. Create a business-ethics index that companies could use to benchmark their behaviour over time

6.3.7. Go beyond compliance as usual

6.4. Reading 8-2: Serving the World's Poor, Profitable

6.4.1. Future

6.4.1.1. Depression:

6.4.1.1.1. Deflation widens the gap between rich and poor.

6.4.1.2. Private investment and widespread entrepreneurial activity, economies of developing regions grow vigorously, creating jobs and weltah and bringing hundreds of millions of new consumers into global marketplace

6.4.2. Which one comes till be determined primarily by one factor:

6.4.2.1. Willingness of big

6.4.3. Untapped potential: Misperception

6.4.3.1. Poor have no money

6.4.3.1.1. Incomes may be low, the aggregate buying power of poor communities is actually quite large

6.4.3.2. Poor are too concerned with fulfilling their basic needs to waste money on nonessential goods

6.4.3.2.1. Poor often do buy luxury items

6.4.3.3. Goods sold are incredibly cheap, hence no room for new competitors

6.4.3.3.1. Consumer are at the bottom of the pyramid pay much more at higher prices

6.4.3.4. Delivering and services are cheap in the world's poor

6.4.3.4.1. Many live in cities that are densely populated today

6.4.3.5. Rural poor lack the buying power

6.4.3.5.1. It is the distribution access which makes it harder

6.4.3.6. Poor cannot use advanced technology

6.4.3.6.1. wrong

6.4.3.7. MNEs only try to exploit markets

6.4.3.7.1. wrong

6.4.4. The Business Case

6.4.4.1. The business opportunities at the bottom of the pyramid has not gone unnoticed

6.4.4.2. Businesses can gain three important advantages by serving the poor:

6.4.4.2.1. 1. Top-line growth.

6.4.4.2.2. 2 Reduced costs: important

6.4.4.2.3. 3. Innovation: Learning

6.4.5. Strategies for serving BOP markets

6.4.5.1. Succeeding in BOP markets requires multinationals to think creatively

7. Lecture 2

7.1. Innovation at Royal DSM

7.1.1. Intro

7.1.1.1. Core value: Sustainability

7.1.1.2. 50% turnover: nutriton

7.1.1.3. B2B company

7.1.1.4. 3P

7.1.1.4.1. People

7.1.1.4.2. Planet

7.1.1.4.3. Profit

7.1.1.5. What drives their market?

7.1.1.5.1. Major problems in the wrld

7.1.1.6. 4 Pillars or growth

7.1.1.6.1. High growth economies

7.1.1.6.2. Innovation

7.1.1.6.3. Sustainability

7.1.1.6.4. Acquisitions and partnerhips

7.1.1.7. Ex of sustainability

7.1.1.7.1. ECO+ driver in animal nutrition

7.1.2. Innovation

7.1.2.1. Research turns money into know-how

7.1.2.2. Innovation turns know how into money

7.1.2.3. Not all R&D units are equal

7.1.2.3.1. Organized in PMC's (Product management consortiums)

7.1.2.3.2. Organized in scientific disciplines

7.1.2.4. Standardized work process for project execution

7.1.2.4.1. The "project management process"

7.1.2.5. Continuous stress between business groups that must make money (short-term) while innovation center has freedom to think beyond short-term vision

7.1.2.5.1. Entrepreneurship agility

7.1.2.6. Why op innovation?

7.1.2.6.1. Because the best scientists probably don't work at DSM

7.1.2.7. Networks make open innovation work:

7.1.2.7.1. Fuzzy front end

7.1.2.8. Venturing; how to mitigate risk

7.1.2.8.1. Because of overload of information

7.1.2.8.2. Not because of money, but to extract value from copmanies

7.1.2.9. Gate 1; business creation

7.1.2.9.1. Convince managment of DSM that idea is attractive and fits DSM

7.1.2.10. Gate 2: new business planning

7.1.2.10.1. Needs true commitment

7.1.3. Emerging business areas

7.1.3.1. 1. Biomedical: DSM's strategic pathway

7.1.3.1.1. Repair, replace, restore and regenerate

7.1.3.1.2. Open innovation in practivce

7.1.3.2. 2. Bio-energy

7.1.3.2.1. Need to teamp up with public-private partnerships for industrial biotechnology

7.1.3.2.2. DSM very global, POET very Local

7.1.3.2.3. Renewability is not enough, need something extra

7.1.3.2.4. Being the launching customer is very important in innovation

7.1.4. Learnings

7.1.4.1. Venturing

7.1.4.1.1. Power to select options

7.1.4.2. Open innovations

7.1.4.2.1. Rejuvenate your business

8. 1. Expanding Abroad

8.1. Chapter 1.

8.1.1. Multinational Enterprise

8.1.1.1. 1. Substantial direct investment in foreign countries

8.1.1.2. 2. Engaged in the active management of offshore assets

8.1.1.3. 3. Regard operations as integral part of the company

8.1.2. New opportunities

8.1.2.1. New markets

8.1.2.2. Low cost resources

8.1.2.3. New sources of knowledge

8.1.3. New challenges

8.1.3.1. Managing strategies

8.1.3.2. More diverse

8.1.3.3. More uncertain

8.1.3.4. More complex

8.1.4. Motivations

8.1.4.1. Main Drivers

8.1.4.1.1. Secure Key supplies

8.1.4.1.2. Market-seeking behaviour

8.1.4.1.3. Access low-cost factors of production

8.1.4.2. Pushes to become MNE

8.1.4.2.1. Starting point: Innovation in home country

8.1.4.2.2. Production processes become standardized

8.1.4.2.3. Product becomes highly standardized

8.1.4.3. Emerging Motivations

8.1.4.3.1. Scale economies, R&D investments, shortening product life cycle

8.1.4.3.2. Gobal scanning and learning capability

8.1.4.3.3. Competitive positioning

8.1.5. Means

8.1.5.1. Prerequisites for Internationalization

8.1.5.1.1. Foreign companies have disadvantages i.c.w. locals

8.1.5.1.2. Foreign Advantages

8.1.5.2. Conditions must be met for existence of MNE

8.1.5.2.1. 1. Motivation

8.1.5.2.2. 2. Strategic competencies

8.1.5.2.3. 3. Organizational capabilities

8.1.5.3. Process of Internationalization

8.1.5.3.1. Developing these competencies

8.1.5.3.2. Build on combination of rational analysis, opportunism and pure luck.

8.1.5.3.3. Foreign market entry = learning process

8.1.5.3.4. Acquire or invest in local competitors

8.1.5.3.5. Born global

8.1.6. Mentalities

8.1.6.1. International

8.1.6.1.1. Company's overseas operations = distant outpost whose main role is to support domestic parent company in different ways.

8.1.6.1.2. Fundamentally domestic with some foreign operations

8.1.6.1.3. Enter only foreign countries with low-psychic distance

8.1.6.2. Multinational

8.1.6.2.1. Develops as managers begin to recognize and emphasize the differences among national markets and operating environments

8.1.6.2.2. More flexible approach

8.1.6.2.3. Built on the multiple nationally responsive strategies to localise products

8.1.6.2.4. Independent entrepreneurs

8.1.6.2.5. Disadvantages:

8.1.6.3. Global

8.1.6.3.1. Creating products for a world market and manufacturing them on a global scale in a few highly efficient plants, often at corporate center.

8.1.6.3.2. Views the world as basic unit of analysis

8.1.6.3.3. Central coordination and control with focus and efficiency

8.1.6.4. Transnational

8.1.6.4.1. Responsive to local market and political needs and pressures to develop global-scale competitive efficiency.

8.1.6.4.2. Capturing benefits of global efficiency

8.1.6.4.3. Resources and activities are specialized

8.2. Case: Acer

8.2.1. Problem statement

8.2.1.1. ACC, a unit of Acer, developed a truly innovative product, but ACC was a problematic unit of Acer. Should the CEO pin his hopes for Acer's next important growth initiative on ACC?

8.2.2. Acer (former multitech):

8.2.2.1. Founded in 1976

8.2.2.2. CEO: Shih

8.2.2.3. Mission: To promote the application of the emerging microprocessor technology.

8.2.2.4. Foundation:

8.2.2.4.1. Capital constrained

8.2.2.4.2. Key employees get substantial ownership

8.2.2.4.3. Acer 1-2-3.

8.2.2.4.4. Result: Company developed reputation to be a very attractive place for bright young engineers.

8.2.2.4.5. Close Knit culture

8.2.2.4.6. Experimenting with joint ventures to expand sales

8.2.3. Birth of the Dragon Dream:

8.2.3.1. Mulitech's sales were doubling each year, confidence was high.

8.2.3.2. Huge potential in overseas expansion

8.2.3.3. Four values of shared believs:

8.2.3.3.1. Human nature is essentially good

8.2.3.3.2. Commitment to maintain a fundamental pragmatism and accountability in all business affairs.

8.2.3.3.3. Belief in placing customer first

8.2.3.3.4. Norm of pooling effort and sharing knowledge.

8.2.4. Professionalization of Acer

8.2.4.1. Paratroopers and Price pressures

8.2.4.1.1. Because internally-grown managers lacked international experience one of the key tasks assigned to the "paratroopers" was to implement the company's ambitious offshore plans.

8.2.4.2. Entry of Leonard Liu:

8.2.4.2.1. Company was in a tailspin

8.2.4.2.2. Shih stepped down as president of Acer Group, handing it over to Liu

8.2.4.2.3. Liu began to focus on opportunities

8.2.4.2.4. Liu gave managers profit and loss responsibility

8.2.4.2.5. Reduction of management layers.

8.2.4.2.6. Introduction of SBUs and RBUs

8.2.4.2.7. 1991 disastrous results: Shih CEO again

8.2.5. Rebuilding the Base:

8.2.5.1. Losses = Personal learning

8.2.5.2. Global brand, local touch philosophy

8.2.5.2.1. Linking the company more closely to its international markets.

8.2.5.3. Client Server Organizaitonal Model

8.2.5.3.1. Taiwan headquarters = a server that used its resources to support client business units, which controlled key operating activities.

8.2.5.4. Fast food business concept

8.2.5.4.1. Biggest challenge: Strategic

8.2.5.4.2. Assemble products close to the customer.

8.2.5.5. The turnaround:

8.2.5.5.1. Fast-food business concept caused inventory turnover to double, reducing carrying costs while lowering the obsolescence risk.

8.2.6. Acer, America and Aspire

8.2.6.1. ACC: ROnald Chwang as head of AAC.

8.2.6.2. First actions; stemming further lossees, reducing inventory levels

8.2.6.3. Birth of Aspire

8.2.6.3.1. New innovation; a PC which does not remind of work.

8.2.7. Shih's Decision

8.2.7.1. Coming back to the problem in the beginning.

8.3. Reading 1-1: The Global Entrepreneur

8.3.1. Entrepreneurs Going Global

8.3.1.1. Companies are being born global today

8.3.1.2. Entrepreneurs hunt for best manufacturing locations because political and economic burden has fallen

8.3.1.3. Scout for talent across the globe

8.3.1.4. Start-ups do business in many different markets before dominating home market.

8.3.1.5. Entrepreneurs cross borders for 2 reasons:

8.3.1.5.1. 1. To be competitive many ventures have to globalize some aspects of their business.

8.3.1.5.2. 2. To take the offensive --> Many new ventures are discovering that new business opportunities spans more than one country or that they can use distance to create new products or services.

8.3.1.6. Key challenges:

8.3.1.6.1. 1. Distance

8.3.1.6.2. 2. Context

8.3.1.6.3. 3. Resources

8.3.2. Competencies Global Entrepreneurs need:

8.3.2.1. 1. Articulating on global purpose

8.3.2.1.1. Developing a crystal clear rationale for being global is critical

8.3.2.2. 2. Alliance building

8.3.2.2.1. Start-ups can quickly attain global reach by string partnerships with large companies headquartered in other countries

8.3.2.2.2. Entrepreneurs enter from positions of weakness

8.3.2.3. 3. Supply-chain creation

8.3.2.3.1. Entrepreneurs must often choose suppliers on the other side of the world and monitor them without having manager nearby. --> Competitive advantage by finding perfect supplier.

8.3.3. How do Diaspora networks help start-ups go global

8.3.3.1. Diaspora networks

8.3.3.1.1. Entrepreneurs can gain access to information, funding, talent, technology and contacts.

8.3.3.2. Taking 4 steps to successfully exploit diaspora networks.

8.3.3.2.1. 1. Map networks

8.3.3.2.2. 2. Identify Organizations

8.3.3.2.3. 3. Tap informal groups

8.3.3.2.4. 4. Identify the influential

8.3.4. How social Entrepreneurs think global

8.3.4.1. Social entrepreneurs are global from birth:

8.3.4.1.1. 1. Disease, malnutrition, poverty, illiteracy and other social problems exist in many developing countries. --> Global problems

8.3.4.1.2. 2. Resources (funds and institution) are mainly in developed countries

8.3.4.1.3. 3. Solution to tackle specific conditions can be applied to other countries.

8.3.5. Entrepreneurs combine social values, profit motive and a global focus.

8.4. Reading 1-2: Distance Still Matters

8.4.1. Cost & Risks created by Distance CAGE-Model

8.4.1.1. Cultural

8.4.1.1.1. How do people interact with each other

8.4.1.1.2. Religious believes, race, social norms

8.4.1.2. Administrative

8.4.1.2.1. Historical and political associations (colonies)

8.4.1.2.2. Uniliteral measures; common barrier to cross-border competition

8.4.1.2.3. Protection of domestic industry

8.4.1.3. Geographic

8.4.1.3.1. Physical size of company

8.4.1.3.2. Average within-country to borders

8.4.1.3.3. Access to waterways and the ocean

8.4.1.3.4. Topography

8.4.1.4. Economic

8.4.1.4.1. Wealth or income of consumers

8.4.1.4.2. Differences in costs and quality for natural resources.

8.5. Reading 1-3: The Tortuous Evolution of the Multinational Corporation

8.5.1. A Rose by Any Other Name

8.5.1.1. Two hypotheses seem to be forming in the minds of executives from international firms that make the extent of their firms' multinationality of real interest.

8.5.1.1.1. 1. The degree of multinationality of an enterprise is positively related to the firm's long-term viability

8.5.1.1.2. 2. A new type of industrial social architecture particular suitable for the latter third of the twentieth century --> Valuable contribution.

8.5.2. Sate of Mind:

8.5.2.1. Difficulty in defining the degree of multinationality

8.5.2.1.1. No single criterion of multinationality is sufficient

8.5.2.1.2. External and quantifiable measures are useful but not enough

8.5.2.2. 3 primary attitudes among international executives toward building a multinational enterprise are identifiable. (EPG-Profile)

8.5.2.2.1. Ethnocentric

8.5.2.2.2. Polycentric

8.5.2.2.3. Geocentric

9. 2. Understanding the International Context

9.1. Chapter 2: Responding to Conflicting Environmental Forces.

9.1.1. Important shifts in political, social, economic and technological forces have combined to create management challenges for todays MNEs.

9.1.2. Forces for Global Integration and Coordination

9.1.2.1. Globalization was brought about by economic, technological and competitive factors.

9.1.2.1.1. These factors changed and transformed the structures of many industries.

9.1.2.2. Forces of Change:

9.1.2.2.1. Scale

9.1.2.2.2. Scope

9.1.2.2.3. Factor Costs

9.1.2.2.4. Free Trade

9.1.2.3. Driving an Expanding Spiral of Globalization

9.1.2.3.1. The spread of global forces expanded from business in which global standardization of products was easy to businesses with consumer's preferences differ from other consumers

9.1.2.4. Global Competitors as change agents

9.1.2.4.1. Most industries were driven to become more globally integrated through external forces of changes.

9.1.2.4.2. Some industries were driven by internal restructuring efforts.

9.1.2.4.3. Scale economies beyond national markets

9.1.2.4.4. Global Chess

9.1.3. Forces for Local DIfferentiation and Responsiveness

9.1.3.1. How to sense, respond to and even exploit differences in the environment of the many different countries in which their company operates?

9.1.3.1.1. National environments differ on many dimensions

9.1.3.1.2. Cultural differences

9.1.3.1.3. Government demands

9.1.3.1.4. Growing Pressures for Localization:

9.1.4. Forces for Worldwide Innovation and Learning

9.1.4.1. Trends created an extremely difficult competitive environment for many industries --> Only if you adapt the forces for global coordination and national differentiation you are able to survive and prosper.

9.1.4.2. Next to the forces described above a new set of forces developed.

9.1.4.2.1. The need for fast globally coordinated innovation

9.1.5. Responding to the Diverse Forces Simultaneously

9.1.5.1. Global industries

9.1.5.1.1. Economic forces of globalization are dominant

9.1.5.2. Multinational industries

9.1.5.2.1. Worldwide businesses in which the dominance of national differences in culture, social and political environments allow multiple national industry structures to flourish.

9.1.5.3. International industries

9.1.5.3.1. Ability to innovate and appropriate the benefits of those innovations in multiple national markets that differentiates the winners from the losers.

9.1.5.4. Transition to Transnationality:

9.1.5.4.1. Centre of gravity: The environment forces that have the most significant impact on the industry's strategic demands.

9.1.5.4.2. Environment forces were replaced by more complex environmental demands

9.1.5.4.3. Localizing forces are growing in strength in global industries such as consumer electronics.

9.2. Case: Global Wine War 2009; New World versus Old.

9.2.1. 2009: Battle between traditional wine makers (France, Italy, Spain) and new industry players (Australia, USA and Chile).

9.2.2. Beginning

9.2.2.1. Quality of wine --> Niche market for premium wine

9.2.2.2. Wine production

9.2.2.2.1. Vineyard horses, row planting --> more efficient

9.2.2.2.2. Small farmers sold grapes to wine maker

9.2.2.2.3. Highly fragmented industry

9.2.2.3. Distribution and marketing

9.2.2.3.1. WIne was sold in buck to merchant traders

9.2.2.3.2. Invention of mass production glass bottles --> Increased vine plantings and expanded production

9.2.2.4. Regulation and classification

9.2.2.4.1. Industry became really important to the cultural and economic life of the producing countries --> political attention --> regulations and laws to control almost every aspect of wine making

9.2.3. Stirring in the New World

9.2.3.1. Opening new markets

9.2.3.1.1. Climate and soil allowed grape growing to flourish in new world --> Consumption varies

9.2.3.1.2. Demand for wine increased rapidly

9.2.3.2. Challenging Production norms

9.2.3.2.1. New world wine producers developed differently from their European counterparty

9.2.3.3. Reinventing the marketing model

9.2.3.3.1. New world producers also innovated in packaging and marketing --> Australian; wine in a box

9.2.3.3.2. Distribution changed as well: controlled full value chain, controlled quality at every step because their name was at final product.

9.2.3.4. The Judgement of Paris

9.2.3.4.1. 24-05-1976 in Paris

9.2.3.4.2. BLind tasting to rate top wines from France and California. Home field advantage for French wine

9.2.3.4.3. American wine won --> Awareness for quality wine of the New World --> fight for export sales.

9.2.3.5. Disruptive change in industry. --> Declining demand for traditional wine producers.

9.2.4. Maturing Markets, Changing Demand:

9.2.4.1. Changing global demand patterns:

9.2.4.1.1. Dramatic decline in demand ocurred in France and Italy

9.2.4.1.2. Key causes

9.2.4.1.3. Demand was growing in wine-importing countries. New market growth (China, Japan)

9.2.4.1.4. Shift in market demand --> escalation of the competition for export sales into a global wine war.

9.2.4.2. Shift to Quality, Rise of Fashion

9.2.4.2.1. Overall volume decline, increased demand for high quality wine.

9.2.4.2.2. Shift to quality --> Rise of fashion

9.2.4.2.3. Increase in demand for white wine --> white wine fits to food

9.2.4.2.4. REd wine demand increased as well --> supposed to be healthy.

9.2.4.2.5. Swings in fashion --> Problem for growers

9.2.4.2.6. 9 new world wines under top 15 wines.

9.2.4.3. Increasing distribution power

9.2.4.3.1. Old world

9.2.4.3.2. New world

9.2.4.4. Ascendancy in of Brand Power

9.2.4.4.1. Wine industry pretard ripe for branding --> Extreme fragmentation of the Old World industry meant that few had the volume to support a branding strategy.

9.2.4.4.2. Just elite wines were recognized brands --> tiny fraction of global market.

9.2.4.5. Government solution:

9.2.4.5.1. Radical shifts in demand proved extremely challenging to Old World procedures.

9.2.4.5.2. EU response:

9.2.4.5.3. New World facing problems as well

9.2.5. The battle for the US Market

9.2.5.1. Chronic oversupply and declining demand in mature markets --> New battle between Old and New world began.

9.2.5.2. The US market

9.2.5.2.1. 2005 Supreme Court allowed interstate wine shipments, triggering a series of state and federal regulation challenges that began to open up the distribution system.

9.2.5.2.2. Battleground in the fight for export: New World vs. Old World.

9.2.5.3. American defense:

9.2.5.3.1. New unexpected source: imported wine from low-cost producing countries

9.2.5.4. Europe's renewed advantage:

9.2.5.4.1. EU Agricultural policy changes --> European wines began growing their market share in the US.

9.2.5.4.2. France highest import value

9.2.5.5. Australia's new challenge

9.2.5.5.1. Exports were stagnating and average price was eroding in UK market.

9.2.5.5.2. Image and price problems in the US market

9.2.5.5.3. Australia's competitive position in the US was being challenged by New World wines from Chile and Argentina.

9.2.6. Behind the Battle Lines: Strategy in France and Australia

9.2.6.1. Weakening prices in Australia

9.2.6.2. 2008: Many believed production declines were over --> Supply increased, producers were not supposed to abandon the long-term strategy and return to earlier practices.

9.2.6.3. France

9.2.6.3.1. Industry and government were responding differently

9.2.6.3.2. Winemakers support national strategy.

9.3. Reading 2-1: Clusters and the New Economics of Competition

9.3.1. Clusters

9.3.1.1. World is dominated by them

9.3.1.2. A striking feuture of virtually evey national, metropolitan economy

9.3.1.3. Silicon Valley, Holleywood

9.3.1.4. Not unique --> very typical

9.3.1.5. Show that the immediate business environment outside a company plays a vital role

9.3.1.6. Lead to new agenda

9.3.2. What is a cluster?

9.3.2.1. Geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field

9.3.2.1.1. An array of linked industries important for competition

9.3.2.1.2. Include: Suppliers of specialized inputs, providers of specialized infrastructure

9.3.2.1.3. Downstream to channels and customers and laterally to manufacturers of complementary products and to companies in industries related by skills

9.3.2.1.4. Include governmental and other institutions (universities) that provide specialized trainings

9.3.2.1.5. Clusters boundaries are defined by the linkages and complementarities across industries and institutions that are most important to competition

9.3.2.1.6. Custer is an alternative way of organizing the value chain.

9.3.3. Why are clusters critical to competition

9.3.3.1. Modern competition depends on productivity

9.3.3.2. Sophistication on how companies compete in particular location --> influenced by quality of local business environment

9.3.3.2.1. legal system and taxes influence all industries

9.3.3.2.2. Decisive aspect of business environment are cluster specific

9.3.3.3. Clusters affect competition in broad ways

9.3.3.3.1. Increasing productivity of companies

9.3.3.3.2. Driving the direction and pace of innovation

9.3.3.3.3. Stimulating the formation of new business --> expand cluster

9.3.3.4. Clusters and productivity

9.3.3.4.1. Being part of a cluster --> Operate more productively in sourcing inputs (accessing information, technology.)

9.3.3.5. Better Access to Employees and Suppliers

9.3.3.5.1. Companies in vibrant clusters can tap into an existing pool of specialized and experienced employees --> lowering costs in recruiting

9.3.3.5.2. Cluster signals opportunity --> Attract talented people

9.3.3.5.3. Cluster offer deep and specialized supplier base

9.3.3.5.4. Clusters better alternatives than formal alliance or vertical integration --> more cost

9.3.4. Access to specialized information

9.3.4.1. Technical and competitive information accumulates within a cluster and members have preferred access to it

9.3.4.2. Information are more transferable

9.3.5. Complementariness

9.3.5.1. Host of linkages among cluster member --> Boost success

9.3.5.2. Complementaries come in many forms:

9.3.5.2.1. Products complement one another in meeting customer's needs

9.3.5.2.2. Coordination of activities

9.3.5.2.3. Marketing --> Enhances reputation of a location

9.3.5.2.4. Buying form a cluster more attractive for customers.

9.3.6. Access to Institutions and Public Goods

9.3.6.1. Investments made by government or other public institutions can enhance a company's productivity

9.3.6.1.1. Ability to recruit employees --> lowering costs.

9.3.7. Better motivation and measurement

9.3.7.1. Local rivalry is highly motivating

9.3.7.2. Peer pressure amplifies competitive pressure in cluster

9.3.7.3. Clusters make it easier to compare and measure performance

9.3.8. Innovation

9.3.8.1. Clusters play a vital role in a company's ongoing ability to innovate

9.3.8.2. Companies inside clusters usually have a better window on the market than isolated companies.

9.3.8.3. Ongoing relationships with other entities within the cluster also help companies to learn early about evolving technology

9.3.8.4. Clusters provide capacity and flexibility to act rapidly

9.3.8.5. Clusters can remain centre for innovation for years.

9.3.9. CLusters and new business formation

9.3.9.1. New companies grow up within an existing cluster rather than at isolated clusters

9.3.9.2. New suppliers proliferate within a cluster --> Concentrated customer base lower the rist

9.3.9.3. Formation of new businesses within a cluster is part of a positive feedback loop

9.3.9.4. Companies in clusters advance relative to rivals at other locations

9.3.10. Birth Evolution and Decline

9.3.10.1. A cluster's birth

9.3.10.1.1. Roots can often be traced to historical circumstances --> MIT in MS

9.3.10.1.2. Arise from unusual, sophisticated or stringent local demand

9.3.10.1.3. Prior existence of supplier industries, related industries or even entire related cluster provided et another seed for new cultures.

9.3.10.1.4. New clusters may also arise from one or two innovative companies that stimulate the growth of many others.

9.3.10.1.5. Chance creates advantageous factors.

9.3.10.2. Evolution:

9.3.10.2.1. Once it started --> Self reinforcing cycle promotes its growth --> expanding = influence

9.3.10.2.2. Growing cluster = opportunity

9.3.10.2.3. Cluster development is vibrant

9.3.10.2.4. Clusters continually evolve as new industries and companies emerge or decline --> Prosper for decades

9.3.10.3. Implications for companies

9.3.10.3.1. What matters most is producitivity

9.3.10.3.2. Executives must extend their thinking beyond what goes on inside their own organizations and within their own industries

9.3.10.3.3. Four issues to strategic agenda

9.3.11. What's wrong with industrial policy

9.3.11.1. Cluster development initiatives should embrace the pursuit of competitive advantage and specialization rather than simply imitate succesful clusters in other locations

9.4. Reading 2-2: Managing Risk in an Unstable World

9.4.1. Politics is Everyone's business

9.4.1.1. Any company in foreign markets need early accurate information on political developments

9.4.1.2. Four reasons

9.4.1.2.1. International markets are more interconnected than ever before

9.4.1.2.2. USA is making the world a more volatile place and has changed risk calculations everywhere

9.4.1.2.3. Offshoring trend is growing --> Businesses shift some operations to countries where labour is cheap

9.4.1.2.4. World is increasingly dependent for energy on states troubled by considerable political risk

9.4.2. What economies can't tell you

9.4.2.1. Economic risk analysis and political risk analysis address two fundamentally different questions

9.4.2.1.1. Economic risk analysis

9.4.2.1.2. Political risk analysis

9.4.3. Strength against shocks

9.4.3.1. Stability: Unit measure of political risk

9.4.3.2. Nation's stability determined by 2 things

9.4.3.2.1. Political leader's capacity to implement policies

9.4.3.2.2. Ability to avoid generating shocks on their own

9.4.3.3. Shocks

9.4.3.3.1. Internal

9.4.3.3.2. External

9.4.4. Risk by the numbers

9.4.4.1. Speculation on the outcomes of these and other scenarios appears in numerous publications

9.4.4.2. A framework

9.4.4.2.1. The analysts

9.4.4.2.2. The data

9.4.4.2.3. The framework

9.4.5. Once you know the odds

9.4.5.1. How companies apply such analysis depends upon their industry, strategy and risk tolerance profile

9.4.5.2. Instability translates into greater risk, risk not always bad thing

9.4.5.2.1. Political risk in underdeveloped countries: upside --> Negative shocks can do little further damage

9.4.5.3. Politics inseperable from markets

10. 3. Developing Transnational Strategies

10.1. Chapter 3: Building Layers of Competitive Advantage

10.1.1. What and how?

10.1.1.1. Global scale efficiency

10.1.1.2. Multinational efficiency

10.1.1.3. Develop innovations

10.1.2. World Wide Competitive Advantage: Goals and Means

10.1.2.1. Develop strategic actions optimizing the achievement of the three conflicting goals

10.1.2.2. 3 different types of tools

10.1.2.2.1. Leverage scale of economies

10.1.2.2.2. Differences in sourcing and market opportunities

10.1.2.2.3. Capitalize on the diversity of activities

10.1.2.3. Strategic challenge

10.1.2.3.1. Exploit all three sources of global competitive advantage

10.1.2.4. KEY:

10.1.2.4.1. Managing the interactions between different goals and different means.

10.1.3. The goals:

10.1.3.1. Global efficiency

10.1.3.1.1. Overall efficiency = ratio of the value of its output to the value of its inputs

10.1.3.1.2. Efficiency improvement is cost reduction and revenue enhancement

10.1.3.1.3. Global integration-national responsiveness framework

10.1.3.2. Multinational flexibility

10.1.3.2.1. Operating environment characterized by diversity and volatility

10.1.3.2.2. Some opportunities and risks generated by this environment are endemic to all firms

10.1.3.2.3. Others are unique to the company

10.1.3.2.4. Multinational flexibility: ability of a company to manage the risks and exploit the opportunities that arise from diversity and volatility of the global government.

10.1.3.2.5. 4 highlight sources of diversity and volatility --> Changes over time and per country

10.1.3.3. World wide learning

10.1.3.3.1. Key asset of MNE is the diversity of environments in which it operates.

10.1.4. The Means

10.1.4.1. 3 fundamental tools

10.1.4.1.1. Exploiting differences in sourcing and market potential across countries

10.1.4.1.2. Exploiting economies of scope

10.1.4.1.3. Exploiting economies of scale

10.1.4.1.4. Mapping Ends and Means: Building blocks for Worldwide Advantage

10.1.5. International, Multinational, Global and Transnational Strategies

10.1.5.1. International strategy

10.1.5.1.1. Companies adopting the broad, international strategy approach focus on creating and exploiting innovations on a worldwide basis, using all different means to achieve this end.

10.1.5.1.2. Advanced countries use it to exploit home-country innovations to develop their competitive position abroad.

10.1.5.1.3. Exploiting parent-company knowledge and capabilities through worldwide diffusion and adaptation

10.1.5.1.4. Sources of core competencies centralized, other decentralized

10.1.5.2. Multinational strategy

10.1.5.2.1. Concentrates primarily on one mean to achieve most of its strategic objectives

10.1.5.2.2. Companies tend to focus to the revenue side

10.1.5.2.3. Building flexibility to respond to national differences through strong, resourceful, and entrepreneurial national opreations

10.1.5.2.4. Decentralized and nationally self-sufficient.

10.1.5.3. Global Strategy

10.1.5.3.1. Depend primarily on developing global efficiency

10.1.5.3.2. Best cost and quality positions for their products

10.1.5.3.3. Building cost advantages through centralized, global-scale operations

10.1.5.3.4. Centralized and globally scaled

10.1.5.4. Transnational Strategy

10.1.5.4.1. Develop a more sophisticated and differentiated configuration of assets and capabilities

10.1.5.4.2. Developing global, efficiency, flexibility, and worldwide learning capability simultaneously

10.1.5.4.3. Dispersed, interdependent and specialized.

10.1.6. Worldwide Competitive Advantage: The Strategic Tasks

10.1.6.1. How can a company respond to the strategic challenges we described?

10.1.6.2. Defending worldwide dominance

10.1.6.2.1. Transnational Characteristic: Companies faced the need to master all three strategic capabilities simultaneously

10.1.6.2.2. Protect particular strength building other capabilities

10.1.6.3. Challenging the Global Leader

10.1.6.3.1. Small companies have challenged the leaders in their businesses

10.1.6.3.2. Processes vary from company to company

10.1.6.3.3. New champions appear to have followed a similar step-by-step approach to building their competitive postitions

10.1.6.4. Protecting Domestic Niches

10.1.6.4.1. Major challenge is to protect domestic niches from worldwide players with superior resources and mutiple sources of competition advantage

10.1.6.4.2. Defend against the competitor's global advantage: counterparty can use their influence in the opposite direction

10.1.6.4.3. Offset the competitor's global strategy

10.1.6.4.4. Approximate the competitor's global advantage

10.2. Case 3-2: United Cereal: Lora Brill's Eurobrand Challenge

10.2.1. Big product launch with "Healthy Berry Crunch"; competitive conditions led Brill to make company's first coordinated Multimarket Business.

10.2.2. United Cereal

10.2.2.1. Wiki

10.2.2.1.1. est. 1910

10.2.2.1.2. Cereals encounter 1/3 of revenue

10.2.2.1.3. Commitment, diligence and loyalty

10.2.2.2. European Operations

10.2.2.2.1. Enterend in 1952

10.2.2.2.2. Expanded its European presence typically by acquiring an established company, to later insert US line

10.2.2.2.3. European Industry & Compettive structure

10.2.2.2.4. Europe Strategy & Organizaiton

10.2.2.2.5. Increasing Price and Profit pressure

10.2.2.2.6. United Cereal Response

10.2.2.3. The Healthy Berry Crunch project

10.2.2.3.1. French opportunity

10.2.2.3.2. European Debate

10.2.2.3.3. Organizational challenge

10.2.2.3.4. Decision time

10.3. Reading 3-1; Managing Differences: The Central Challenge of Global Strategy

10.3.1. Global strategy: 2 assumptions

10.3.1.1. Central challenge is to strike the right balance between economics of scale and responsiveness to local conditions

10.3.1.2. The more emphasis companies place on scale economies in their worldwide operations, the more global their strategies will be.

10.3.2. Problematic!

10.3.2.1. Main goal of any global strategy:

10.3.2.1.1. Manage large differences that arise at borders

10.3.2.2. Ignore other important functional response: arbitrage

10.3.3. New framework for approaching global integration that gets around the problems outlined above

10.3.3.1. AAA Triangle

10.3.3.1.1. Adaption

10.3.3.1.2. Aggregation

10.3.3.1.3. Arbitrage

10.3.3.2. Understanding the AAA triangle