1. Final steps (optional)

1.1. Download notebook into the repo

1.2. Download any files you have created in Colab

1.2.1. they will be erased when session is over

1.3. open it using Jupyter (from ANACONDA)

1.4. export it as HTML (keep the **index** file name)

1.5. commit and push

1.6. publish the html

2. Previous Steps

2.1. I. Creating accounts

2.1.1. The place in the cloud where we will save our files

2.1.2. Easy way to use Python (for free)

2.1.2.1. If you have GMAIL, you have colab!

2.2. II. Installations

2.2.1. Programming Languages

2.2.1.1. Python

2.2.1.1.1. Anaconda

2.2.2. Applications

2.2.2.1. GitHub Desktop

2.3. Data for the Session

2.3.1. **I**. On your GitHub

2.3.1.1. create a repo for this session (**spatial data**)

2.3.1.1.1. **clone** the repo to a location on your local computer

2.3.2. II. In Your **LOCAL** repo (in your personal computer)

2.3.2.1. add content (from Canvas) to your local repo

2.3.2.1.1. file of USA

2.3.2.1.2. file of Peru

2.3.2.2. Sync local repo with cloud

2.3.2.2.1. Open the GitHub app in your local machine

2.3.2.2.2. commit

2.3.2.2.3. push

2.4. In Colab

2.4.1. Create new notebook

2.4.2. name it "index"

3. Coding I: **Getting Ready**

3.1. The Libraries needed

3.1.1. verify Colab has

3.1.1.1. pysal

3.1.1.2. pandas

3.1.1.3. geopandas

3.2. TheData

3.2.1. Read the Maps from GitHub

3.2.1.1. Go back to GitHub

3.2.1.1.1. get URL for each

3.2.1.2. using GeoPandas

3.2.1.2.1. activate

3.2.1.2.2. use **read_file** function

3.2.1.2.3. using geopandas:

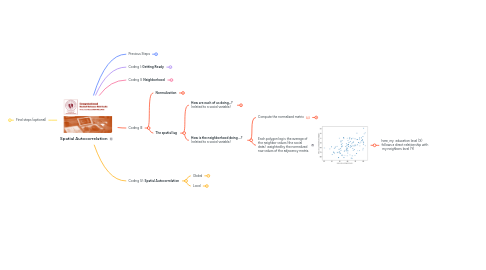

4. Coding II: **Neighborhood**

4.1. previous steps

4.1.1. activate PYSAL!

4.1.1.1. from libpysal.graph import Graph

4.1.1.1.1. terminology

4.1.2. set random seed

4.1.2.1. so you can get my results

4.2. geometries touch each other in any portion of their boundaries?

4.2.1. YES: contiguity

4.2.1.1. rook

4.2.1.1.1. you are my neighbor if we share at least a line segment on our boundaries

4.2.1.2. queen

4.2.1.2.1. you are my neighbor if we share at least a boundary point

4.2.1.3. either may generate isolates

4.2.1.4. Notice we created these wide matrices for pedagogical purposes. It is a bad idea if you have many columns and rows.

4.2.2. NO

4.2.2.1. Close **enough** to be considered a neighbor

4.2.2.1.1. YES: proximity

4.2.2.1.2. NO: not a neighbor (am I an ISLAND?)

5. Coding III

5.1. **Normalization**

5.1.1. all previous matrices SUM by ROW

5.1.1.1. the sum by row

5.1.1.1.1. unnormalized weights

5.1.2. normalized weights

5.1.2.1. transforming values per row

5.1.2.1.1. a row adds to 1 (ONE)

5.2. **The spatial lag**

5.2.1. **How are each of us doing...?** (related to a social variable)

5.2.1.1. choropleth: **share of population that completed high school **

5.2.2. **How is the neighborhood doing ...?** (related to a social variable)

5.2.2.1. Compute the normalized matrix

5.2.2.1.1. to weight social data values of neighbors

5.2.2.2. Each polygon lag is the average of the neighbor values (the social data) weighted by the normalized row values of the adjacency matrix.

5.2.2.2.1. here, my education level (X) follows a direct relationship with my neighbors level (Y)

6. Coding IV: **Spatial Autocorrelation**

6.1. Global

6.1.1. my variable values is affected by my neighbors' variable values?

6.1.1.1. Moran's I

6.1.1.1.1. coefficient (similar to Pearson's R) measuring the relationship between a variable and its lag

6.2. Local

6.2.1. my local situation is affected by my neighbors situation?

6.2.1.1. Moran's LISA

6.2.1.1.1. reveals autocorrelation clusters