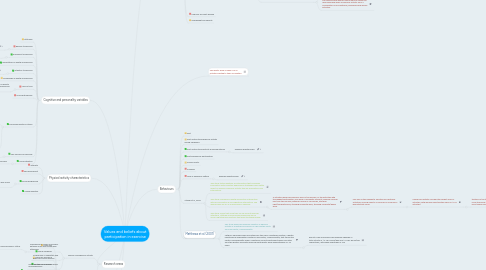

1. Cognitive and personality variables

1.1. Attitudes

1.2. Barriers to exercise

1.2.1. Example questionnaire

1.3. Enjoyment of exercise

1.3.1. Example questionnaire

1.4. Expectation of health and exercise

1.4.1. Example questionnaire

1.5. Intention to exercise

1.5.1. Example questionnaire

1.6. Knowledge of health and exercise

1.7. Lack of time

1.7.1. Lack of Time for Physical Activity: Perception or Reality for African American and Hispanic Women (Heesch and Mâsse, 2004)

1.8. Mood disturbance

1.9. Perceived health or fitness

1.9.1. Health Belief Model (6 concepts)

1.9.1.1. Perceived susceptibility

1.9.1.1.1. Many don't consider themselves at risk even if told (e.g. when asked to reduce fat intake)

1.9.1.2. Perceived severity

1.9.1.3. Perceived benefits

1.9.1.4. Perceived barriers

1.9.1.5. Self efficacy

1.9.1.6. Cues of action

1.9.2. Example questionnaire for health Belief Model

1.10. Self efficacy for exercise

1.10.1. Example questionnaire

1.11. Self motivation

1.11.1. Example questionnaire

2. Social environment

2.1. Class size

2.2. Group cohesion

2.3. Physician influence

2.4. Past family influence

2.5. Social support, friends and peers

2.6. Social support, spouse and family

2.7. Social support staff and instructor

2.8. Gyuresik, Bray, and Brittain, 2004

2.8.1. Findings

2.8.1.1. Females identified several barriers to being vigorously active within the first two weeks of their freshman year of college, including social invitations during preferred exercise times and high academic workloads.

2.8.1.2. Barriers

2.8.1.2.1. Intrapersonal

2.8.1.2.2. Interpersonal

2.8.1.2.3. Institutional

2.8.1.2.4. Community

2.8.1.2.5. Physical environment

2.8.2. Methods

2.8.2.1. Identify five barriers to partaking in physical activity. They were then asked to rate themselves as to how they think they could overcome these barriers (this measures coping self efficacy). Task self efficacy was determined by rating their perception for completing the chosen physical activity

3. Physical environment

3.1. Climate and season

3.1.1. Association Between Weather and Physical Activity in Baltimore Teens (O'Neill et al, 2011)

3.1.1.1. PA data (measured by accelerometry) from 331 predominately urban, African American (70%) high school students from the Baltimore Active Living Teens Study were analyzed. Daily temperature and precipitation were significantly associated with PA. After adjusting for age, race, gender, and maternal education

3.1.1.2. weather was associated with adolescents’ PA, which suggests a need for a more diverse array of PA options not affected by weather

3.2. Cost

3.3. Disruption and routine

3.4. Access to facilities: actual

3.4.1. Equity of access to physical activity facilities in an English city (Panter, Jones and Hillsdon, 2007)

3.4.1.1. A cross sectional geographical study was conducted in six neighbourhoods in the city of Norwich in August and September 2004. Participants were ( n = 401) adults who received, completed, and returned questionnaires. Road distances to facilities were calculated using Geographical Information System

3.4.1.2. People in low income households, who are more likely to adopt low levels of activity, are least well served by affordable facilities that would enable them to become more active. If the British Government is to meet targets for improving levels of physical activity, it may need to consider how market forces might be creating an inequitable distribution of facility provision

3.5. Access to facilities: perceived

3.5.1. Fitness Facilities for Adults: Differences in Perceived Access and Usage (Kruger, Carlson and Kohl, 2007)

3.5.1.1. Cross-sectional analysis of a national sample of 27,894 adults from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey was performed to describe the characteristics of those who perceived that they have access to fitness facilities, and determine the prevalence of perceived access, reported use of fitness facilities, and reported barriers to the use of fitness facilities.

3.5.1.2. Fitness facilities provide one option for increasing access to places to be physically active. Having access to fitness facilities is significantly associated with physical activity levels among U.S. adults

3.6. Home equipment

4. Physical activity characteristics

4.1. Intensity

4.2. Perceived effort

4.3. Group programme

4.3.1. Effect of a group intervention in the primary healthcare setting on continuing adherence to physical exercise routines in obese women (Del Rey-moya et al, 2013)

4.4. Leader qualities

5. Research areas

5.1. Women and physical activity

5.1.1. Differences in values and beliefs between male and female gym attendees

5.1.1.1. Income and socioeconomic status

5.1.2. Differences in sedentary and physically active women

5.1.3. Reasons why some women prefer group exercise?

5.2. Age

5.2.1. Differences in perceived benefits of physical activity for young and old

5.2.2. The effect of social environment factors on exercise adhesion

6. The results show a mean of 5.22 activities related to their occupation.

7. Behaviours

7.1. Diet

7.2. Past unstructured physical activity during childhood

7.3. Past unstructured activity during adulthood

7.3.1. Example questionnaire

7.4. Past programme participation

7.5. School sports

7.6. Smoking

7.7. Type A behaviour pattern

7.7.1. Example questionnaire

7.8. Stadler et al, 2009

7.8.1. This study tested whether an intervention that combined information with cognitive behavioural strategies had a better effect on women's physical activity than an information only intervention.

7.8.2. This study compared a health information intervention with an information & self regulation intervention. 256 women ages 30-50 in a large area in Germany.

7.8.2.1. 5 activities were performed by 50% of the women. of the activities with the highest participation, five were of moderate intensity, walking carrying less than two pounds, walking carrying 2-25 pounds, standing light/moderate work, standing moderate work, standing moderate/heavy work.

7.8.2.1.1. only one of the frequently reported occupational activities, moving objects 75 pounds or more had a high intensity code.

7.8.3. This study found that more than 40.2% did not exercise. Intentions, attitude and perceived behavioural are all social cognitive preconditions that effected these people.

7.9. Matthews et al. (2001)

7.9.1. This study examined seasonal variation in physical activity in longitudinal analyses of 580 healthy adults from Worcester, Massachusetts.

7.9.2. Method: Individuals were recruited from the Fallon Healthcare System, a health maintenance organization located in Worcester, Massachusetts, that serves the central Massachusetts region. Additional Minority participants were recruited from the greater Worcester area.The participants were aged between 20-70 years.

7.9.2.1. Results: Men and women had seasonal changes in total activity of 1.4 MET-hours/day and 1.0 MET-hours/day respectively, with peak amplitudes in July

8. Demographics

8.1. Age

8.1.1. Well researched, yet little understood: young adults and physical activity; What do young adults think and feel about their physical activity experiences (Cothran and Kulinna, 2005)

8.1.2. Jennifer L. Han a , Mary K. Dinger a , Holly R. Hull a , Nichole B. Randall a , Kristiann C.Heesch b & David A. Fields

8.1.2.1. Few studies have examined physical activity during the transition from high school to college.

8.1.2.2. Purpose:To examine changes in physical activity and physical activity patterns among females during the transition from high school to college.

8.1.2.3. Methods: Sixty-nine females (age 18.2±0.4 years; body mass index 21.8±2.6 kg/m2; 84% Caucasian) at a large university in the south central United States participated in this prospective longitudinal study. They com-pleted a questionnaire at the beginning of their freshman and sophomore years of college, recalling their participation in physical activity in the previous 12 months

8.1.2.4. Results: Weekly time spent in moderate, vigorous, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity declined between high school and college (p<0.01). Physical activity participation also differed by semester (p<0.01), with a significant decline during the summer between high school and college (p<0.01), and an additional decrease during the first semester of college (p<0.01).

8.2. Blue-collar occupation

8.3. Education

8.4. Gender (male)

8.4.1. Maureen O’Dougherty, Mary O Hearst, Andrea Y Arikawa Steven D Stovitz,Mindy S Kurzer, Kathryn H Schmitz, 2012

8.4.1.1. The Majority of women do not meet recommendedphysical activity (PA) guidelines. Assessment onchanges in PA patterns among young, healthy USwomen was therefore performed

8.4.1.1.1. Participants aged 18–30years had completed a randomized controlledaerobics trial

8.4.1.1.2. A two-sample test of proportions testedthesample changes in PA; a pairedttest assessed the within-person changes.

8.4.1.1.3. regression modelassessed the demographic predictors of meeting PA levelsin year 2 (6months post-intervention). Women who metthe recommended PA used a combination of leisure andlifestyle PA at both timepoint

8.4.2. Physical activity patterns of young women post college graduation LuAnn et al. (2008)

8.4.2.1. Method random sample of 1,000 women aged between 18-23 questionairre to assess weight status, dieting pattern, PA and psych effects Format of questionairre two pages, 26 questions and took around 15 mins to do Psyh affinity of food the questions came form the adolescent survey

8.4.2.2. Findings Dieitng patterns 66% reported not on a weight loss diet but 77% had done before bmi 9% subjects wanted to be under wieght 84% wanted to be normalweight PA patterns average time spent exercsing 22mins per day Only 31% of women where exercising Psychological affinity for food The results show women have a distorted psychological relationship with food

8.4.2.3. Conculsion There is a sig difference between dieters and non dieters for the following bmi, psychological affinity for food and desired body weight.

8.4.3. Wilbur, Michaels Miller, Montgomery, Chandler, 1998

8.4.3.1. A 24 cell quota sample stratified by four occupations, two races and three age groups.

8.4.3.1.1. One hundred seventy-six women ages 35-65, who worked 20 or more hours a week and are not currently using hormone replacement therapy, not pregnant and did not have a hysterectomy before 35 years of age.

8.4.3.2. Five patterns of household and leisure activity were identified: vigorous, continuous, cumulative, occasional and inactive.

8.4.3.2.1. Participation in the viperous pattern was low, but 34% followed a continuous pattern of leisure activity and 75% followed a continuous pattern of household activity

8.4.3.2.2. The results show woman may be able to obtain the recommended levels of physical activity from a combination of occupational, household and leisure activities.