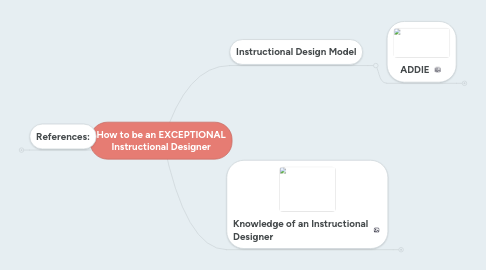

1. Instructional Design Model

1.1. ADDIE

1.1.1. Analyze

1.1.1.1. 1. Needs Assessment (NA) -Central activity of a Front-Ended Analysis

1.1.1.1.1. Assessment is needed when actual performance < expected/ optimal performance

1.1.1.1.2. Purpose

1.1.1.1.3. Methods

1.1.1.2. 2. Performance Analysis

1.1.1.2.1. Definition for performance problem

1.1.1.2.2. 2 Possible explanations

1.1.1.2.3. Models for analyzing performance problems

1.1.1.3. 3. Task Analysis

1.1.1.3.1. Purpose

1.1.1.3.2. Methods

1.1.1.3.3. Criteria for analysis

1.1.1.4. 4. Learner Analysis

1.1.1.4.1. Wrong assumptions (Smith & Ragan, 2005)

1.1.1.4.2. Important assumptions

1.1.1.4.3. 4 categories for analyzing learning characterisitcs (Smith & Ragan, 2005)

1.1.1.5. Reflection

1.1.1.5.1. To be a good instructional designer, we need to have the ability to get information from different stakeholders by asking the right questions. It may not always be easy to get to the essence of the topic and find out where a problem lies, what is the gap, how big is the gap and whether a gap is worth fixing or not. A successful instructional designer is like a doctor. He or she is not a subject matter expert, but he/she needs to make use of the information he/she finds out to diagnose a problem and give the best advice.

1.1.2. Design

1.1.2.1. 1. Devising the Training Objectives/ Performance

1.1.2.1.1. Purpose (Mager, 1984, Smaldino, Lowther and Russell, 2012)

1.1.2.1.2. Goals vs. Objectives

1.1.2.1.3. Approach

1.1.2.2. 2. Sequencing and designing the instruction

1.1.2.2.1. Macro-level

1.1.2.2.2. Micro-level

1.1.2.3. Reflection

1.1.2.3.1. As an English teacher, I love reading about the different theories on lesson planning, planning of instructions giving and designing materials. I found it fascinating and useful when I read something I didn’t know and I’m happy when a research reinforces what I am already doing. Lesson planning and designing materials is what teachers do in an everyday basis; as such, it is wonderful to experiment and improve upon what I’m doing in my classroom according to what I have learnt from the literature.

1.1.3. Develop

1.1.3.1. People involved

1.1.3.1.1. Web/ media developer

1.1.3.1.2. Instructional Designer (I. D.)

1.1.3.1.3. Subject Matter Expert (S. M. E.)

1.1.3.1.4. HR/ CD manager

1.1.3.1.5. Technical support specialists

1.1.3.2. Phases of development

1.1.3.2.1. Inquiry

1.1.3.2.2. Target

1.1.3.2.3. Review existed resources

1.1.3.2.4. Determine instructional materials

1.1.3.2.5. Delivery mode

1.1.3.2.6. Develop instructional materials

1.1.3.2.7. Synthesize Platform

1.1.3.2.8. Validation

1.1.3.2.9. Update

1.1.3.3. Reflection

1.1.3.3.1. I thought development would be a very simple and easy part of instructional design. However, after going through the readings, I realize that it is more complicated than I previously thought. There are a lot of phases involved in the development process. One particular phase that strikes me most is the trial stage, the trying out of the prototype. I really do think it makes a big difference if people are allowed to try an innovation for an extended period of time before making the decision of buying the innovation or not. It is especially true for teachers. Very often, it is already demanding for teachers to learn a new innovation for teaching. It could be very overwhelming if they have to make a decision of buying an innovation for the school or not before they get to really test it out with real students in a real lesson. After all, it would be quite disastrous if the school bought something that is later found unsuitable. This could be one possible reasons why teachers are often not enthusiastic about adopting new innovations in schools.

1.1.4. Implement

1.1.4.1. Definition

1.1.4.1.1. to put something into effect or action

1.1.4.2. Key Concepts of implementation (Smith & Ragan, 2005)

1.1.4.2.1. 1. Diffusion

1.1.4.2.2. 2. Dissemination

1.1.4.2.3. 3. Adoption

1.1.4.2.4. 4. Stakeholders

1.1.4.3. Principles for Encouraging Implementation (Smith & Ragan, 2005, p.306)

1.1.4.3.1. Adopting System

1.1.4.3.2. The people

1.1.4.3.3. The instructional materials

1.1.4.3.4. Awareness

1.1.4.3.5. Trials

1.1.4.3.6. Teacher/trainer training

1.1.4.4. Implementation of Instructional Product

1.1.4.4.1. Testing

1.1.4.4.2. Employing

1.1.4.5. Reflection

1.1.4.5.1. Before reading all those reference books about instructional designs, I have never thought about how to encourage implementation. It is eye-opening to find out all the ways to put forward innovation, the group of people to pay attention to and to persuade. So far, I haven’t had the chance to implement anything, but I imagine that as an educator, with new curriculums and iPad being a more and more prominent teaching tool, there would definitely be times when I need to help with implementation of some sort and these knowledge will certainly be useful.

1.1.5. Evaluate

1.1.5.1. Defintion

1.1.5.1.1. Assess the quality of the instructional products and processes, both before and after implementation

1.1.5.2. Processes

1.1.5.2.1. 1. Determine Evaluation Criteria

1.1.5.2.2. 2. Select evaluation tools

1.1.5.2.3. 3. Conduct evaluation

1.1.5.3. Evaluators

1.1.5.3.1. Clients

1.1.5.3.2. Real users

1.1.5.3.3. Design team

1.1.5.3.4. Development team

1.1.5.4. Ways to evaluate instructional materials (Smith & Ragan, 2005)

1.1.5.4.1. Formative Evaluation

1.1.5.4.2. Summative Evaluation

1.1.5.5. Kirkpatrick’s (1994) techniques for conducting the evaluation (Craig, 1996)

1.1.5.5.1. Four criteria/ levels/ steps

1.1.5.6. Reflection

1.1.5.6.1. Evaluation is indeed of paramount importance. As seen from the ADDIE diagram, evaluation is the centre and basically connected to every element in ADDIE. We need to have evaluation before and after implementation, evaluate on the analysis, the design, the development and the implementation and the success of the whole project is dependent on how well evaluation is done. There are different types of evaluations as well, formal and informal, summative and formative; and they serve different functions. To be a good instructional designer, deciding on appropriate types of evaluation to be done and the suitable methods is definitely a monumental task.

2. References:

2.1. Bangert, A. W. (2004). The Seven Principles of Good Practice: A framework for evaluating on-line teaching. Internet and Higher Education, 7, 217-232.

2.2. Blanchard, P. N. & Thacker, J. W. (2007). Effective training : systems, strategies, and practices (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall.

2.3. Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987, March). Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3–7.

2.4. Churchill, D., King, M., Webster, B. & Fox, B. (2013). Integrating Learning Design, Interactivity, and Technology (pp.139-143). In H. Carter, M. Gosper and J. Hedberg (eds.), Electric Dreams. Proceedings ascilite 2013 Sydney.

2.5. Craig, R. L. (1996). The ASTD training and development handbook : a guide to human resource development. New York: McGraw-Hill.

2.6. Gagne, R., Briggs, L. & Wager, W. (1992). Principles of Instructional Design (4th Ed.). Fort Worth, TX: HBJ College Publishers.

2.7. Gagné, R. M., Briggs, L. J., & Wager, W. F. (1985). Principles of instructional design. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

2.8. Gilbert, T. F. (1978). Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

2.9. Harless, J. (--). Accomplishment Based Curriculum Development. Newnan: Harless Performance Guild.

2.10. Havelock, R. G., & Zlotolow, S. (1995). The change agent’s guide to innovation in education (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

2.11. Jonassen, D. H. (2003). The vain quest for a unified theory of learning. Educational Technology, July-August, 5-8.

2.12. Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educational Technology: Research & Development, 48 (4), 63-85.

2.13. Keller, J. M. (2010). Motivational Design for Learning and Performance: The ARCS Model Approach. Boston, MA: Springer.

2.14. Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1994). Evaluating training programs: the four levels (1st ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

2.15. Krathwohl, David R. (2002). "A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: An overview". Theory Into Practice (Routledge) 41 (4): 212–218.

2.16. Mager, R. F. (1992). What Every Manager Should Know About Training. Belmont: Lake Publishing Company.

2.17. Mager, R. F. (1984). Preparing instructional objectives (2nd ed.). Belmont, Calif.: Pitman Management and Training.

2.18. Mager, R. F. & Pipe, P. (1984). Analyzing Performance Problems (2nd ed.). Lake Publishing Company. Belmont. CA.

2.19. Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2005). Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

2.20. Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

2.21. Merrill, M. D., -. (2013). First principles of instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 43-59.

2.22. Merrill, M.D., (2002). Five Principles of Instruction, Educational Technology, Research & Development, 50(3), 43-59.

2.23. Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: The Free Press.

2.24. Rossett, A. (1992). Handbook of Human Performance Technology: Analysis of Human Performance Problems. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

2.25. Smaldino, S., Lowther, D. & Russell, D. (2012). Instructional technology and media for learning (10th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

2.26. Smaldino, S. E., Russell, J. D., Heinich, R., & Molenda, M. (2005). Instructional technology and

2.27. media for learning. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

2.28. Smith, P. L. & Ragan, T. J. (2005). Instructional design (3rd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: J. Wiley & Sons.

2.29. Spitzer, D. (1991). Introduction to Instructional Technology (2nd ed.). Boise State University.

2.30. Wile, D. (2007). Why doers do. Performance + Instruction, 35(2), 30-35.

3. Knowledge of an Instructional Designer

3.1. What is learning? (Jonassen, 2003)

3.1.1. a relatively permanent change in behavior

3.1.2. information processing

3.1.2.1. take in information, hold it briefly in short-term memory until they can find a place to store it permanently in long term memory

3.1.2.2. Faced with a task, retrieve information from long-term memory and shift it into working memory where we can use the information

3.1.3. remembering and recalling

3.1.3.1. a process of “knowledge acquisition"

3.1.4. social negotiation

3.1.4.1. Humans naturally tend to share their meaning with others

3.1.4.2. more likely results from conversations than cramming

3.1.5. thinking skills

3.1.5.1. logical thinking

3.1.5.1.1. judging the relationships between meanings of words and statements

3.1.5.2. critical thinking

3.1.5.2.1. knowing how to judge ideas

3.1.5.3. pragmatic thinking

3.1.5.3.1. considering the background or purpose of the judgment and the decision as to whether the statement is good enough for the purpose (Ennis, 1989)

3.1.6. activity

3.1.6.1. one cannot act without thinking or think without acting (Leont'ev, 1972)

3.2. 3 Main Theoretical Models of Learning Theories

3.2.1. ○ Behaviourism

3.2.1.1. Main assumptions

3.2.1.1.1. Learning is a relatively permanent change in observable behaviour (Jonassen, 2003)

3.2.1.2. Basic concepts

3.2.1.2.1. Observable permanent change in behaviour / action

3.2.1.2.2. not interested in the learners' mind or emotions

3.2.1.2.3. Black-box metaphor of the learner

3.2.1.3. Two types of conditioning

3.2.1.3.1. Classical conditioning

3.2.1.3.2. Operational conditioning

3.2.1.4. Implication to Learning

3.2.1.4.1. Learning Objectives

3.2.1.4.2. Practice with feedback

3.2.1.4.3. Types of reinforcement, punishment

3.2.1.5. Reflection

3.2.1.5.1. Behaviorism is quite an interesting learning theory. According to Behaviorism, it is possible to condition a person’s behavior through operant conditioning, through the consequences. There are some issues with this theory, however. First, we do not always need to experience the reward or punishment to learn something. Humans also learn from observation. For instance, we do not need to have taken drugs and suffer from the consequences before knowing not to take them. This is not taken into account in this theory.

3.2.2. ○ Cognitivism/ cognitive information processing

3.2.2.1. Main assumptions

3.2.2.1.1. Learning as information transmission & processing.

3.2.2.1.2. Learning viewed as the acquisition of new information.

3.2.2.2. Basic concepts

3.2.2.2.1. Focus on the mental processes (e.g., memory)

3.2.2.2.2. Computer metaphor

3.2.2.3. Information Processing Model

3.2.2.3.1. Cognitive Information Processing Model (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968)

3.2.2.3.2. Stage theory

3.2.2.4. Cognitive Information Processing (CIP) Model

3.2.2.4.1. Input

3.2.2.4.2. Sensory memory/ register

3.2.2.4.3. Attention

3.2.2.4.4. Short-term memory

3.2.2.4.5. Encoding/Retrieval

3.2.2.4.6. Long-term memory

3.2.2.5. Implications to Learning

3.2.2.5.1. Gain learners’ attention

3.2.2.5.2. Recall prior knowledge

3.2.2.5.3. Recognize limitations of the working memory

3.2.2.5.4. Encourage multiple representations for encoding

3.2.2.5.5. Provide organized instruction to facilitate encoding

3.2.2.6. Reflection

3.2.2.6.1. The implications drawn from Cognitivism in particular coincide with my own experiences in teaching. First, it is essential to catch the learners’ attention. Second, we often start with raising questions that can activate students’ schemata and prior knowledge and we tend to ask them to share what they know with their classmates before teaching anything new. Recognizing the limitations of the working memory, we would use different ways of encoding to help our students to memorize concepts and facts, e.g. chunking of long vocabulary into syllables.

3.2.3. ○ Constructivism

3.2.3.1. Main assumptions

3.2.3.1.1. Inquiry learning

3.2.3.1.2. Problem-based learning (PBL)

3.2.3.1.3. Self-directed learning

3.2.3.2. Basic concepts

3.2.3.2.1. Meaning is imposed by people and cultures

3.2.3.2.2. Schools should not just be concerned about the achievement gap but also the relevance gap (Perkins, D.)

3.2.3.3. Types of construtivism

3.2.3.3.1. Personal/individual constructivism

3.2.3.3.2. Social constructivism

3.2.3.4. Constructivist conditions for learning (Driscoll, 2000)

3.2.3.4.1. Embed learning in relevant and realistic settings

3.2.3.4.2. Provide for social negotiation

3.2.3.4.3. Encourage ownership in learning

3.2.3.4.4. Nurture self-reflection of knowledge construction

3.2.3.5. Reflection

3.2.3.5.1. After hearing a lot of Dr. Hew’s experiences on teaching through constructivism, I’m sad to say that I have never used constructivism during my teaching practices or during my year as a practicing English teacher. I would say that learning done through constructivism will probably be very memorable, quite long-lasting, as well as throughout. Usually people use constructivism for problem-based learning. It is not very appropriate for areas that are highly divergent, say in the arts, literature, ethics, since it is more of a matter of opinions, rather than finding solutions to something. I like the idea of making use of constructivism for teaching and learning. However, I must admit that it would mean teachers have to spend a lot more time on lesson planning and it is quite time consuming as well. It might be tricky to find the time to learn through constructivism under the pressure of a tight syllabus. Also, since I’m teaching English, it might be challenging to find a suitable topic to teach through constructivism.