1. The Catholic Reformation

1.1. Loyola and the Jesuit Order

1.1.1. In the 1530s Loyola founded the Society of Jesus, the most important of the many new monastic orders associated with the Catholic Reformation.

1.1.2. The Jesuit order was a fascinating amalgam of two elements mysticism and militant religious zeal. The first emphasized the personal and intuitive experience of God, while the second involved an attitude of unquestioned submission to the Church as the absolute source of truth.

1.2. Mannerist Painting

1.2.1. The spatial clarity, symmetry, and deco- rum of High Renaissance painting gave way to Manner- ism, a style marked by spatial complexity, artificiality, and affectation. Their paintings mirrored the self-conscious spirituality and the profound insecurities of an age of religious wars and political rivalry.

1.3. Parmigianino

1.3.1. The traits of the Mannerist style can be seen in the Madonna of the Long Neck by Parmigianino (1503–1540). In this landmark work the tra- ditional subject of Madonna and Child is given electric theatricality.

1.4. El Greco

1.4.1. A master painter who worked in Italy and Spain in the service of the Church and the devout Philip II (1527–1598), El Greco produced visionary canvases marked by bold distortions of form, dissonant colors, and a daring handling of space.

1.5. Music and the Catholic Reformation

1.5.1. In an effort to rid sacred music of secular influence, the Council of Trent condemned the borrowing of popular tunes, which had been absorbed by religious music since the late Middle Ages. It also banned complex polyphony, which tended to obscure the sacred text.

2. The Italian Baroque

2.1. Italian Baroque Architecture

2.1.1. Italian Baroque churches became the models for Catholic worship throughout Europe and Latin America. They featured wide naves, huge domes, and ornate altarpieces.

2.1.2. To design the piazza (the broad public space in front of the basilica), the Church commissioned one of the leading architects of the day, Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598–1680).

2.2. Italian Baroque Sculpture

2.2.1. Bernini was not only the chief architect of seventeenth-century Rome, he was also one of its leading sculptors. To the rendering of a life-sized marble figure of the biblical David

2.2.2. For the Cornaro Chapel of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, he created a landmark multimedia altarpiece: The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa

2.3. Italian Baroque Painting

2.3.1. Visual drama and theatricality were hallmarks of Italian Baroque painting. artists made use of bold contrasts of light and dark, along with a perspective device known as foreshortening, by which figures or objects (depicted at an angle to the picture plane) appear to recede in space.

2.4. Caravaggio

2.4.1. In his paintings, Caravaggio renounced the Grand Style—noble figures, dignified setting, and graceful symmetry—of his High Renaissance predecessors.

2.4.2. True to the ideals of the Catholic Reformation, Caravaggio’s paintings appealed to the senses rather than to the intellect. They also introduced into European art a new and vigorously lifelike realization of the natural world—one that inventively mingled the sacred and the profane.

2.5. Gentileschi

2.5.1. Born in Rome, Artemisia Gentile- schi (1593–1653) was the daughter of a highly esteemed painter, himself a follower of Caravaggio.

2.5.2. Her landmark canvas Judith Slaying Holofernes which compares in size and impact with Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of Saint Peter, illustrates the decapitation of an Assyrian general and enemy of Israel at the hands of a clever Hebrew widow.

2.6. Pozzo

2.6.1. A master of the techniques of linear perspective and dramatic foreshortening, the Jesuit architect and sculptor Andrea Pozzo (1642–1709) made the ceiling above Sant’Ignazio’s clerestory appear to open up.

2.6.2. Pozzo underlines the global ambitions of Roman Catholic evangelism by adding at the four corners of the ceiling the allegorical figures of Asia, Africa, Europe, and America.

3. The Northern Baroque

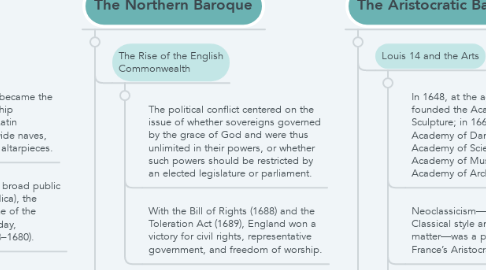

3.1. The Rise of the English Commonwealth

3.1.1. The political conflict centered on the issue of whether sovereigns governed by the grace of God and were thus unlimited in their powers, or whether such powers should be restricted by an elected legislature or parliament.

3.1.2. With the Bill of Rights (1688) and the Toleration Act (1689), England won a victory for civil rights, representative government, and freedom of worship.

3.2. The King James Bible

3.2.1. The new translation, known as the King James Bible, preserved the spiritual fervor of the Old Testament Hebrew and the narrative vigor of the New Testament Greek.

3.3. Donne

3.3.1. Donne held the position of dean at Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London. There he developed the sermon as a vehicle for philosophic meditation. The language of his sermons is notable for its extended metaphors, or “conceits.”

3.4. Milton

3.4.1. John Milton (1608–1674) was a devout Puritan and a staunch defender of the antiroyalist cause. He challenged English society with expository prose essays on a number of controversial subjects.

3.4.2. Considered the greatest of modern epics, Paradise Lost is a mirror of the Baroque imagination: vast in its intellectual sweep, theatrical in its staging, and wide-ranging in its allusions to history and literature.

3.5. The London of Christopher Wren

3.5.1. In 1666, a devastating fire tore through London and destroyed three-quarters of the city, including 13,000 homes, eighty-seven parish churches, and the cathedral church of Saint Paul’s, where John Donne had served as dean some decades earlier.

3.5.2. Wren prepared designs for the reconstruction of London; he was commis- sioned to rebuild more than fifty churches, including Saint Paul’s—the first cathedral in Christendom to be completed in the lifetime of its architect

3.6. Seventeenth- Century Holland

3.6.1. Declar- ing their independence in 1581, seven of these provinces in the North Netherlands would establish a predominantly Calvinist Dutch Republic (later called “Holland”). During the seventeenth century, this self-governing state became one of the most commercially active territories in Western Europe.

3.6.2. Ostensibly a celebra- tion of earthly life, the painting—a type known as vanitas— suggests the corruptibility of worldly goods, the futility of riches, and the inevitability of death.

3.7. Vermeer

3.7.1. The Dutch artist Jan Vermeer (1632–1675) was a master at depicting light. Vermeer represented his immediate surroundings with a directness and intimacy that have led scholars to suggest that his pictures were conceived with the aid of a camera obscura, a seventeenth-century optical device that anticipated the modern pinhole camera.

3.8. Rembrandt

3.8.1. A keen observer of human character and a master technician, Rembrandt became the leading portrait painter in the Dutch capital of Amsterdam.

3.8.2. A consummate printmaker, Rembrandt used the burin (a steel tool) to develop dramatic contrasts of rich darks and theatrical lights.

4. The Aristocratic Baroque

4.1. Louis 14 and the Arts

4.1.1. In 1648, at the age of ten, Louis founded the Academy of Painting and Sculpture; in 1661 he established the Academy of Dance; in 1666, the Academy of Sciences; in 1669, the Academy of Music; and in 1671, the Academy of Architecture.

4.1.2. Neoclassicism—the revival of Classical style and subject matter—was a prime ingredient of France’s Aristocratic Baroque style.

4.1.3. In order to exercise greater con- trol over the French nobility, Louis moved his capital from Paris to Versailles.

4.2. Theater Arts

4.2.1. To provide musi- cal entertainments for state dinners, balls, and theatrical performances, Louis established a permanent orchestra, the first in European history. All members of the court were expected to perform the basic court dances, including the very popular minuet.

4.2.2. By 1700, there emerged a system of abstract symbols for recording specific dance steps and movements, thus initiating the art of choreography.

4.3. Academic Art

4.3.1. painters were enjoined to follow the formalized rules of the Grand Style, inspired by the High Renaissance works of Raphael. Artists should choose only serious and elevated subjects (such as battles, heroic actions, and miraculous events) drawn from Classical or Christian subject matter.

4.4. The Aristocratic Baroque Portrait

4.4.1. Aristocratic portraits reflected an individual’s outward appearance, often to the point of idealization. The landmark example of French aris- tocratic portraiture is the magnificent likeness of Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud.

4.5. Velazquez and Rubens

4.5.1. Velázquez painted a variety of Classical and Christian subjects, but his landmark enterprise was the informal group portrait known as Las Meninas

4.5.2. A contemporary of Velázquez, the internationally renowned Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) established his reputation in the courts of Europe. One of Rubens’ most memorable canvases, the Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus ,depicts the abduction of two mortal women by the Roman heroes Castor and Pollux.

5. Baroque Music

5.1. Giovanni Gabrieli (1555–1612), principal organist at Saint Mark’s Cathedral ushered in a new and dramatic style of polychoral and instrumental religious music.

5.2. Gabrieli

5.2.1. Gabrieli was among the first to specify an instrument for each part in the musical composition, earning him the name the “father of orchestration.” He was also one of the first composers to write into his scores the words piano (soft) and forte (loud) to govern the dynamics

5.2.2. Finally, Gabrieli is credited with advancing a system of major–minor tonality that came to dominate Western music.

5.3. The Birth of Opera

5.3.1. The earliest performances of Western opera resem- bled the Renaissance masque—a form of musical enter- tainment that included dance and poetry, along with rich costumes and scenery. Baroque operas were more musi- cally complex, however, and more dramatically cohesive than most Renaissance masques.

5.4. Vivaldi

5.4.1. Vivaldi, nicknamed “il Prete Rosso” (“the Red Priest,” for his flaming red hair), composed dozens of oratorios and more than forty operas. But he is best known for his 456 concertos, written for various musical instruments, includ- ing the cello, the flute, the oboe, the bassoon, the guitar, and, most notably, the violin.

5.5. Monteverdi

5.5.1. Monteverdi wrote various kinds of religious music, as well as ballets, madrigals, and operas. His compositions reflect a typically Baroque effort to infuse music with the vocal expressiveness and emotional charge of poetry.

5.5.2. Orfeo (1607), composed for the duke of Mantua, was Monteverdi’s first opera. The instrumentalists performed the overture, an orchestral introduction to the opera. They also accompanied vocal music consisting of arias (elaborate solo songs or duets) alternating with recitatives (passages spoken or recited to sparse chordal accompaniment). And he introduced such novel and expressive instrumen- tal effects as pizzicato.

5.6. Music at the Court of Louis 14

5.6.1. The Italian-born composer Jean- Baptiste Lully (1632–1687), also administered the Royal Academy of Music. Lully developed the single most characteristic feature of French opera: the inclusion of formal dance

5.7. Handel and the English Oratorio

5.7.1. Handel composed forty-six operas in Italian and four in his native German. He also produced a prodigious number of instrumental works. But it was for his development of the oratorio that he earned fame among the English, who called him “England’s greatest composer.”

5.7.2. Handel’s oratorios are essentially homophonic; that is, their musical organization depends on the use of a dominant melody supported by chordal accompaniment.

5.7.3. The use of the figured bass (also called the “continuo,” since it played throughout the piece) was one of the main features of Baroque music.

5.7.4. The most famous of Handel’s oratorios is Messiah (1742), which was written in the English of the King James Bible.

5.8. Instrumental Music

5.8.1. By the early eighteenth century, musicians were adopting the system of tuning known as equal temperament, whereby the key- board was divided into semitones of equal value, making it easy to transpose a melody from one key to another.

5.8.2. Northern Italy was the world center for the manufacture of violins.

5.8.3. The sonata (from the Italian sonare, “to sound”) is a musical form written for an unaccompanied keyboard instrument or for another instrument with keyboard accompaniment.

5.8.4. The suite, written for any combination of instruments, is a series of move- ments derived from European court or folk dances.

5.8.5. The concerto (from the same root as concertato, describing opposing bodies of sound) features two groups of instru- ments—one small, the other large—playing in “dialog.”

5.9. Bach and Instrumental Music

5.9.1. A fugue (literally “flight”) is a polyphonic compo- sition in which a single musical theme (or subject) is re-stated in sequential phrases.

5.10. Bach claimed that his study of Vivaldi had taught him to “think musically,” and to endow the creative process with “order, coherence, and proportion.”

5.11. Bach and Religious Music

5.11.1. As organ master and choir director of the Church of Saint Thomas in Leipzig, Bach composed music for the Sunday services and for holy days. The most important component of Lutheran worship was the cantata, a multi-movement piece composed of a text sung by chorus and soloists, who are accompanied by musical instruments.