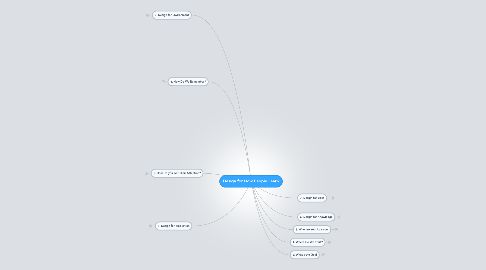

1. 4. How Do We Remember?

1.1. Memory In & Out

1.1.1. Sensory Memory

1.1.1.1. Habituation

1.1.1.1.1. DF: Getting used to a sensory stimulus

1.1.1.1.2. Can help learner

1.1.1.2. DF: First filter of everything you sense.

1.1.2. Short-term (working) Memory

1.1.2.1. What do you retain?

1.1.2.1.1. Repetition

1.1.2.2. What's the limit?

1.1.2.2.1. depends on person

1.1.2.3. What Does This Mean for Learning Design?

1.1.2.3.1. "chunking" info helps

1.1.2.4. DF: If you pay attenetion it goes to short-term memory.

1.1.2.4.1. It's probably something

1.1.2.4.2. Gatekeeper for LTM

1.1.3. Long-term Memory (or is it in your closet?)

1.1.3.1. Where Do You Put It?

1.1.3.1.1. Anything you remember becomes part of a series of associations.

1.1.3.1.2. more/better associations, i.e. "shelves" make it easier to retrieve info.

1.1.3.2. Multiple Shelves

1.1.3.2.1. Poorly Constructed Shelves

1.1.3.2.2. Crowded Shelves

1.1.3.2.3. Unintended Shelves

1.1.3.3. In-Context Learning

1.1.3.3.1. Scenario 1 - Teach about new cell phones

1.1.3.3.2. Scenario 2 - Teach college students to make healthy meals.

1.1.3.3.3. Scenario 3

1.1.3.4. Emotional Context

1.1.3.4.1. Use role-playing

1.1.3.4.2. Create pressure

1.1.3.4.3. Invest in high-quality stories, acting, and performance

1.1.3.4.4. DF: difficult to create; helps learners do what they know they should do.

1.1.3.5. Encoding For Retrieval, or How Will It Need to Be Used?

1.1.3.5.1. will they need to...

1.1.3.5.2. A practical example

1.1.3.5.3. How can you create learning activities that are a good match for the real-world application?

1.1.3.5.4. Practice needs to match eventual use.

1.1.3.6. Real Vs. Perceived Knowledge

1.1.3.6.1. We think we know a thing simply because we recognize it - applying it is different.

1.2. Types of Memory

1.2.1. Categories

1.2.1.1. What you know you know

1.2.1.1.1. Explicit memory

1.2.1.2. What you don't know you know

1.2.1.2.1. Tacit memory

1.2.1.3. What you only think you know

1.2.1.4. Types within categories

1.2.1.4.1. Declarative or Semantic Memory

1.2.1.4.2. Episodic Memory

1.2.1.4.3. Conditioned Memory

1.2.1.4.4. Procedural Memory

1.2.1.4.5. Flashbulb Memories

1.3. Repetition and Memory

1.3.1. Learning almost always requires practice and learning

1.3.2. When you learn something new, connections between neurons form. Connections strengthened with repetition.

1.3.3. Memorization: The Blunt Force Solution

1.3.3.1. Clunky way to learn

1.3.3.2. Puts information on just one shelf

1.3.3.3. Can't use it in multiple contexts

1.3.3.4. Likely to have only sequential but not random access

1.4. Summary

1.4.1. Memory relies on encoding and retrieval, so learning designers need to think about how the material gets into long-term memory, and also what the learner can do to retrieve it later.

1.4.2. Learners are besieged with a constant flow of input, and things need to be significant to the learner to attract their attention.

1.4.3. People habituate to monotonous stimuli, so learning needs not to fall into a repetitive drone.

1.4.4. Working memory has its limits, and it's easy to overwhelm a new learner. Limit or chunk the flow of new information to make it more manageable.

1.4.5. People hold items in their working memory only as long as they need them for some purpose. Once that purpose is satisfied, they frequently forget the items. Asking your learners to do something with the information causes them to retain it longer and increases the likelihood that the information will be encoded into long term memory.

1.4.6. The organization of long-term memory has an impact on a learner's ability to retrieve material. The material will be easier to retrieve if it is grounded in a rich context and accessible in multiple ways (i.e. on multiple shelves).

1.4.7. Matching the emotional context of learning to the emotional context of retrieval improves the likelihood that the learner will be able to successfully use the material.

1.4.8. Storytelling leverages an existing mental framework, and therefore information given in story forms can be easier to retain than other types.

1.4.9. Repetition and memorization will work to encode information into long-term memory, but it's a limited strategy. This process can be tedious for learners and doesn't provide very many pathways for retrieval.

1.4.10. There are many different types of memory, and utilizing multiple types can improve the likelihood the material is retained.

2. 5. How Do you Get Their Attention?

2.1. If They're Not Paying Attention?

2.1.1. Need to "talk to the elephant"

2.2. Talk to the Elephant

2.2.1. Brain is like being a rider and an elephant

2.2.1.1. 2 separate parts of the brain

2.2.1.1.1. Conscious verbal thinking brain

2.2.1.1.2. automatic, emotional, visceral brain

2.2.2. The Rider

2.2.2.1. is conscious, controlled thought

2.2.3. The Elephant

2.2.3.1. is everything else

2.2.3.1.1. gut feelings, visceral reactions, emotions etc.

2.2.3.2. The elephant WANTS, but the rider restrains

2.2.4. The Elephant is Bigger and Stronger

2.2.4.1. We over estimate riders control

2.2.5. What Does This Mean for Your Learners?

2.2.5.1. If the elephant isn't engaged, the learner is going to have difficulty paying attention

2.2.5.2. Dragging elephant to where it doesn't want to go is exhausting, cognitively

2.2.5.3. Cognitive resources of memory, focus, and control are finite. You can control the elephant, only not for very long.

2.2.5.4. Asking learners to rely entirely on will power and concentration is like asking the rider to drag the elephant uphill

2.2.6. Attract the Elephant

2.2.6.1. Engage learner at visceral level

2.3. Ways to Engage the Elephant

2.3.1. Tell It Stories

2.3.1.1. People Like Stories

2.3.1.1.1. They go on existing shelves

2.3.1.1.2. There's a logical flow

2.3.1.1.3. Stories create suspense

2.3.1.1.4. Stories aren't boring (we hope)

2.3.1.1.5. The Hero

2.3.1.1.6. Urgency

2.3.1.1.7. Emotional Resonance

2.3.2. Surprise It

2.3.2.1. Unexpected Rewards

2.3.2.1.1. We react more strongly to unexpected rewards

2.3.2.1.2. Unexpectedness part of reason we like sports, comedy etc.

2.3.2.2. Dissonance

2.3.2.2.1. When we bump into something that doesn't fit our view of the world. Purple dog.

2.3.2.2.2. Can expand learner's mental model and be a teachable moment.

2.3.2.3. The Elephant is a Curious Creature

2.3.2.3.1. Ask interesting questions

2.3.2.3.2. Be mysterious

2.3.2.3.3. Leave stuff out

2.3.2.3.4. Be less helpful

2.3.3. Tell It All The Other Elephants Are Doing It

2.3.3.1. Ways to leverage social engagement

2.3.3.1.1. Collaboration

2.3.3.1.2. Social Proof

2.3.3.1.3. Competition

2.3.3.2. Elephant is a social creature & pays more attention when others are involved.

2.3.4. Show it Shiny Things

2.3.4.1. Use Visuals, But Be Careful

2.3.4.1.1. Know why you are adding a visual

2.3.4.1.2. Visuals help distribute the load

2.3.4.1.3. Visuals can help build shelves

2.3.4.1.4. Visuals provide context

2.3.4.2. Elephant is very visual

2.3.5. Let The Elephant Play With Stuff

2.3.5.1. The elephant is a tactile creature, so hands-on learning helps create auditory, visual and physical stimulation to attract attention.

2.3.6. Make With the Funny

2.3.6.1. Humor is subjective, so make sure learners are receptive.

2.3.6.2. Helps with recall

2.4. Prizes! Rewards! Stuff!

2.4.1. What's Good About Rewards

2.4.1.1. Provide immediacy

2.4.2. What's Bad About Rewards

2.4.2.1. A bad reward is something extrinsic to the learning experience

2.4.2.2. Extrinsic rewards can demotivate people - once you start paying people, it becomes work.

2.4.3. Making Rewards More Intrinsic

2.4.3.1. You don't to decide what's intrinsic to the learner.

2.4.3.1.1. Need to be genuinely satisfying to the learner

2.4.3.2. Want to give learners autonomy in deciding what is meaningful

2.4.3.2.1. Ways to provide autonomy

2.5. Summary

2.5.1. Talk to the emotional, visceral brain (elephant) as well as the conscious, verbal brain (rider).

2.5.2. Attracting attention is not the same as maintaining attention. Make sure the device you use to attract attention is intrinsic to the material being learned. If it's not, it may actually be distracting and negatively impact learning.

2.5.3. Some ways to attract your learners' attention include stories, emotional resonance, urgency, surprise, and interesting puzzles.

2.5.4. Social interaction and visual cues will go a long way to attracting and maintaining attention.

2.5.5. Devices like competition and extrinsic rewards will attract your learner's attention, but they almost certainly will distract them from the real goal and have a negative impact on their intrinsic motivation. They are best avoided unless used very carefully.

2.5.6. Intrinsic rewards almost always require learner autonomy or choice to be effective.

3. 8. Design for Motivation

3.1. 2 Types

3.1.1. Motivation to do

3.1.1.1. We Learn from Experience

3.1.1.1.1. Texting while driving example

3.1.1.1.2. Classic "I know, but..." activities

3.1.1.1.3. Remember, Change is Hard

3.1.1.2. Designing for Behavior

3.1.1.2.1. Models

3.1.2. Motivation to learn

3.2. Summary

3.2.1. There are two kinds of motivation that learning designers need to consider: motivation to learn, and motivation to do.

3.2.2. When you hear “I know, but...,” that’s a clue that you’ll probably need to design for motivation.

3.2.3. “I know, but...” frequently comes up when there is a delayed reward or consequence.

3.2.4. We learn from experience, but it can be a problem if we learn the wrong thing from experience.

3.2.5. Change is hard.

3.2.6. We are creatures of habit— irritating for the short-term learning curve, but potentially useful if we can help learners develop a new habit.

3.2.7. You may be able to influence your learners, but you can’t control them.

3.2.8. Learning designs should show the learners how something new is useful and easy to use.

3.2.9. Try to ensure your learners get the opportunity to observe and personally try new processes or procedures.

3.2.10. Learners need to feel a sense of self-efficacy with the new challenge or skill.

3.2.11. Use opinion leaders as examples.

3.2.12. Visceral experiences may have more impact that abstract ones, although the research on this topic is ongoing.

4. 9. Design for Environment

4.1. Environment Gaps

4.2. Knowledge In The World

4.2.1. Learning the Right Things

4.2.2. Proximity Matters

4.3. Putting Resources In The World

4.3.1. Job Aids

4.3.1.1. Types

4.3.1.1.1. Decision Trees

4.3.1.1.2. Reference Information

4.3.1.1.3. Augmented reality

4.3.2. Supply Caching

4.4. Putting Prompts/Triggers In The World

4.5. Putting Behaviors In The World

4.6. Clearing the Path

4.6.1. Always ask these questions

4.6.1.1. Can we make the process simpler?

4.6.1.2. Can we make the system better?

4.6.1.3. What barriers are keeping people from succeeding?

4.6.2. The Big Question

4.6.2.1. What's everything else we could do (besides training) that will allow learners to succeed?

4.7. Summary

4.7.1. Instead of trying to put all the knowledge into the learners’ heads, try to figure out if some of the knowledge can be put into the environment instead.

4.7.2. Activities that are particularly difficult for humans to master are good candidates for embedding into the environment.

4.7.3. Proximity matters— try to get the knowledge as close to the behavior as possible.

4.7.4. When designing for environment, remember that recognizing the right option is easier than recalling it.

4.7.5. Don’t just teach learners how to do a process; look at the process to see if there’s any way to streamline it to make it simpler and easier to perform.

5. 1. Where Do We Start?

5.1. The Learner's Journey

5.1.1. Learning experiences are like journeys. The journey starts where the learner is now, and ends when the learner is successful (however that is defined). The end of the journey isn’t just knowing more, it’s doing more.

5.2. Where's the Gap?

5.2.1. There’s a gap between your learner’s current situation and where they need to be in order to be successful. If you can identify those gaps, you can design better learning experiences.

5.3. Identify and Bridging Gaps

5.3.1. Types of Gaps

5.3.1.1. Knowledge Gaps

5.3.1.1.1. Information is the equipment your learners need to have in order to perform. Having information doesn’t accomplish anything by itself. Something is accomplished when the learner uses that information to do things. Basically, you want your learners to have the right supplies for their journey.

5.3.1.1.2. What information does the learner need to be successful?

5.3.1.1.3. When along the route will they need it?

5.3.1.1.4. What formats would best support that?

5.3.1.2. Skills Gaps

5.3.1.2.1. Having a skill is different than having knowledge. To determine if something is a skill gap rather than a knowledge gap, you need to ask just one question: Is it reasonable to think that someone can be proficient without practice? If the answer is Yes, then it’s not a skill, but if the answer is No, then you know you are dealing with a skill, and your learners will need practice to develop proficiency.

5.3.1.2.2. What will the learners need to practice to develop the needed proficiencies?

5.3.1.2.3. Where are their opportunities to practice?

5.3.1.3. Motivation and Attitude Gaps

5.3.1.3.1. If somebody knows what to do, but chooses not to do it, that’s a motivation gap. There are a number of reasons for motivation gaps. It could be that the person doesn’t really buy into the outcome or destination.

5.3.1.3.2. "Change" or unlearning is a special motivational gap

5.3.1.4. Environment Gaps

5.3.1.4.1. What in the environment is preventing the learner from being successful?

5.3.1.4.2. What is needed to support them in being successful?

5.3.1.4.3. Environment gaps can take a lot of different forms in an organization.

5.3.1.5. Communication Gaps

5.3.1.5.1. Sometimes someone is failing to perform isn’t due to a lack of knowledge but because they have bad directions. This isn’t really a learning issue— this is a miscommunication issue.

5.4. Examples

5.4.1. Scenario 1: Marianna

5.4.1.1. New supervisor for IT department

5.4.1.2. Can't keep up with paperwork or manage her direct reports

5.4.1.3. What gaps are relevant for Marianna?

5.4.1.3.1. Not a knowledge problem. Needs a lot more guided practice to develop the skills to perform tasks efficiently and well. Also, some attitude and motivation gaps that make her reluctant to use what she knows. Specific coaching from manager will be more helpful than additional classes. Also, changing elements in her environment might help with paperwork.

5.4.2. Scenario 2: Marcus

5.4.2.1. Teaching a two-day workshop on database design for a new database technology.

5.4.2.2. Reviewed textbooks

5.4.2.3. Most were experienced database designers there specifically to learn the new technology. Some complained about functionality of new technology. Marcus felt caught out when students wanted explanation of why things had to be done a particular way.

5.4.2.4. What gaps are relevant for Marcus?

5.4.2.4.1. His first time around, Marcus focused more on database design skills, which his audience didn’t really need. His audience does have a knowledge gap around the functionality of the new system. Also, some attitude/ motivation gaps that are likely the product of his learners being forced to do things differently than they are accustomed to. If Marcus can focus on getting his audience comfortable with the specific software functionality and how it can be useful for them, his second class will probably go better.

5.4.3. Scenario 3: Alison

5.4.3.1. Project manager for web design company teaching an undergraduate project-management class at a design school.

5.4.3.2. Students 18-19 yrs old taking class because it's required.

5.4.3.3. What gaps are relevant for Alison?

5.4.3.3.1. No indication of a communication issue, but Alison will need to accommodate all of the other types of gaps. Students don’t have work experience, and don’t have much project-management knowledge. Will need to develop the skills to apply what she teaches. Will need to have elements in their environment to support what they learn. Given that it’s a required course, and that her students are primarily art and design students, she needs to think about how to encourage their attitude and motivation.

5.5. Why This Is Important

5.5.1. If you don’t start with the gaps, you can’t know that your solution will bridge them. If you have a really clear sense of where the gaps are, what they are like, and how big they are, you will design much better learning solutions.

5.6. Summary

5.6.1. A successful learning experience doesn’t just involve a learner knowing more— it’s about them being able to do more with that knowledge.

5.6.2. Sometimes a learner’s main gap is knowledge, but more frequently knowledge and information are just the supplies the learner needs to develop skills.

5.6.3. Use the question “Is it reasonable to think that someone can be proficient without practice?” to identify skills gaps. If the answer is no, ensure that learners have opportunities to practice and develop those skills.

5.6.4. You need to consider the motivations and attitudes of your learners. If they know how to do something, are there other reasons why they aren’t succeeding?

5.6.5. Change can be hard because learners may have deeply ingrained patterns they have to unlearn, and you need to expect that as part of the change process.

5.6.6. The environment needs to support the learner. People are much less likely to be successful if they encounter roadblocks when they try to apply what they’ve learned.

5.6.7. Sometimes it’s not a learning problem, but rather a problem of communication, direction, or leadership. Recognizing those instances can save a lot of effort in wrong directions.

5.6.8. If you have a well-defined problem, you can design much better learning solutions. It’s always worth clearly defining the problem before trying to define the solution.

6. 2. Who are Your Learners

6.1. Understanding your learners is part of designing good learning experiences.

6.2. What do you want to know about your users?

6.2.1. Basic demographic information (such as age, gender, job, or role).

6.2.2. Things like their reading level or how they use technology if that's relevant.

6.3. What Do Your Learners Want?

6.3.1. Why Are they There?

6.3.1.1. The “Just tell me what I need to know” learner

6.3.1.1.1. Would be happy with a list of what to do and a quick run through

6.3.1.2. The “I need to solve a problem” learner

6.3.1.2.1. e.g. "plumbing for dummies"

6.3.1.3. The “Oooh – Shiny!” learner

6.3.1.3.1. Short, distributed attention

6.3.1.4. The “Hey! this is cool!” learner

6.3.1.4.1. Rampant curiousity

6.3.1.5. The “This is a required course” learner

6.3.1.5.1. May need to be convinced material is useful

6.3.1.6. The “I fear change” learner

6.3.1.6.1. Needs to be convinced change is useful and doable

6.3.1.7. The “I pretty much know all of this already” learner

6.3.1.7.1. Doesn't want beginner material; understands quickly and gets the subtlties

6.3.2. Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

6.3.2.1. Intrinsically motivated learners are interested in the topic for its own sake, or have a specific problem they are trying to solve.

6.3.2.1.1. How to Handle

6.3.2.2. Extrinsically motivated learners are motivated by an outside reward or punishment. Any kind of learning that is “required” is likely to be extrinsically motivated.

6.3.2.2.1. How to Handle

6.3.3. Your Learners Want not to Feel Stupid

6.3.3.1. Your job is to make your learners feel smart and, even more important, they should feel capable.

6.3.3.2. The “I don’t want to feel stupid” learner (everyone)

6.3.3.2.1. How to Handle

6.3.4. What Do Your Learners Like?

6.3.4.1. If they like food, use it in an example.

6.4. What Is Their Current Skill Level?

6.4.1. Could be novice, proficient or expert.

6.4.2. Suggestions for accommodating experts

6.4.2.1. Don’t make them hate you. Don’t make every part of the learning experience required for everybody. Just don’t.

6.4.2.2. Consider pull vs. push.

6.4.2.2.1. Pull means you provide the resources, lessons, and reference materials and the learners choose when they need them. You want to make them as easy to find and as accessible as possible, but you don’t need to force them through it.

6.4.2.3. Leverage their expertise. These are smart people! Figure out ways to make use of that. Can they coach novices?

6.4.2.4. Embed some of the novice information.

6.4.2.5. Let them test out (maybe - haven't seen many good pre-tests).

6.4.2.6. Ask “Do you need anything?” and then get out of their way.

6.4.3. Scaffolding

6.4.3.1. Scaffold the Incline What if the topic is too complicated for novice learners to really tackle without hopelessly oversimplifying the content?One of the ways to deal with this is scaffolding.

6.4.3.2. Examples

6.4.3.2.1. Reduce the complexity of the environment.

6.4.3.2.2. Use walkthroughs.

6.4.3.2.3. Provide supports.

6.5. How Are Your Learners Different From You?

6.5.1. Respect your learners, for they are not you.

6.5.2. What is your learner's context?

6.5.2.1. You may have a mental picture of the topic, but your learners may not.

6.5.3. How Much You Know Vs How Much They Know

6.5.3.1. Let’s say you are teaching an introductory course on something you know a lot about. But of course you can’t talk to a novice audience the same way you’d talk to a colleague. So what’s the bigger barrier?

6.5.4. Why Your Brain is Like a Closet

6.5.4.1. But when you hand content to a novice learner, that person is likely to look perplexedly at the piece of information that they have no context for, shrug, and toss it onto the pile of other information accumulating on the floor of their closet.

6.5.4.2. How Do You Help Novices Structure Their Closets?

6.5.4.2.1. The first thing you need to do is help your learners build a few shelves.

6.5.5. The Experience Filter

6.5.5.1. Everyone’s understanding is colored by their previous experience, and therefore everybody’s understanding of the same material will be a bit different.

6.5.6. How Can You Know What Your Learners Are Thinking?

6.5.6.1. Regardless of the learning venue (classroom, e-learning, informational website), it’s best to have as interactive an experience as possible, so information flows both ways.

6.6. Learning Styles

6.6.1. The idea espoused by learning-style advocates was that if we could identify individual differences in how people learn, we could provide them with learning experiences that best match their learning styles and improve learning outcomes.

6.6.2. What Can I Do With Learning Styles?

6.6.2.1. Not everyone learns the same way.

6.6.2.1.1. Even if you can’t adapt a learning situation to someone’s unique learning style, you can create learning experiences that incorporate a variety of approaches.

6.6.2.2. There are different kinds of intelligence.

6.6.2.2.1. I used to teach art students, and they loved learning about multiple intelligences because it validated their skills and abilities that fell outside of the traditional definition of IQ.

6.6.2.3. We are more alike than we are different.

6.6.2.3.1. Excepting certain physical impairments, we all learn from visual, auditory, and kinesthetic methods, and we have all the different types of intelligence at varying levels.

6.6.2.4. You may want to vary the learning approach depending on the subject being learned.

6.6.2.4.1. While there is little evidence to support customizing learning to a particular learner’s style, there is some evidence that suggests that you should adapt the learning approach to the content being taught.

6.7. Methods for Learning About Your Learners

6.7.1. Talk to Your Learners

6.7.1.1. They will tell you how it works, not how it should work

6.7.1.2. They can tell you where it hurts.

6.7.1.3. They can give you examples and context.

6.7.1.4. Questions for learners

6.7.1.4.1. Why are you learning this?

6.7.1.4.2. How will learning this help you (how are they motivated)?

6.7.1.4.3. What are the biggest hassles or challenges you experience (in relation to the topic)?

6.7.1.4.4. What are some examples of when you’ve had problems?

6.7.1.4.5. What was the hardest thing for you to learn?

6.7.1.4.6. What were the easy parts?

6.7.1.4.7. What could make it easier for you?

6.7.1.4.8. How do you use this information now?

6.7.1.4.9. What do you wish you knew when you first started?

6.7.1.4.10. Can you walk me through it?

6.7.1.4.11. What does a typical example look like?

6.7.1.4.12. What crazy exceptions have you seen?

6.7.2. Follow Your Learners Around

6.7.2.1. Context, context, context

6.7.2.1.1. People remember more in a similar environment than they do in a dissimilar environment, and the more context (visual or situational) that you can leverage, the better people will remember.

6.7.2.2. Even new learners have started to build some shelves.

6.7.2.2.1. If you’re asking them about what they do, they are already starting to gloss over details, but if you watch them in their actual environments, you see what’s happening, and can stop and get more information, e.g., “Can you tell me more about that step you just did?”

6.7.2.3. Juicy details.

6.7.2.3.1. If you are trying to create good examples or scenarios for learning, you can get the best details from seeing people in their actual environments. If you know about their world, you can create better examples, scenarios, and activities much more easily.

6.7.3. Try Stuff Out With Your Learners

6.7.3.1. Nothing will show up gaps like trying stuff out. Are there parts where people get confused? Do certain parts drag? Do you find yourself talking for a long time in the middle? Was your test audience confused by the instructions for an activity? Testing your learning design early and often will allow you to fix these things before you get in front of your official learners.

6.7.3.2. Reasons why important

6.7.3.2.1. You think you are being clear, but you know how it’s supposed to work.

6.7.3.2.2. You’ll get good ideas.

6.7.3.2.3. It’s more efficient in the end.

6.8. Summary

6.8.1. You want to know about your learners— not just about their demographics, but about their motivation, likes and dislikes, skill level, and about how they understand the world.

6.8.2. Provide more structure for your new learners, and more resources and autonomy for your experienced learners.

6.8.3. Don’t just hand your learners information, but instead help them construct and organize their framework for that information.

6.8.4. Learning experiences should be two-way interactions, so you know when learners understand correctly, and when they don’t.

6.8.5. All of the theory in the world won’t help you as much as spending time in your learners’ world, and testing your designs early and often.

7. 3. What's the Goal

7.1. Determine Goals

7.1.1. Whenever you are designing a learning experience, it’s critical to have clear goals defined. If you don’t know where you are and where your learners need to be, you can’t figure out how to get them there.

7.1.1.1. Identify what problem you are trying to solve

7.1.1.2. Set a destination

7.1.1.3. Determine the gaps between the starting point and the destination

7.1.1.4. Decide how far you are going to be able to go

7.2. Identify the Problem

7.2.1. A lot of learning projects start with the goal, rather than the problem, but that puts you in the position of solving problems you don’t actually have, while failing to address the real issues.

7.2.1.1. Questions to ask

7.2.1.1.1. What bad thing will happen if they don’t know this?

7.2.1.1.2. What are they actually going to do with this information?”

7.2.1.1.3. How will you know if they are doing it right?

7.2.1.1.4. What does it look like if they get it wrong?

7.2.1.1.5. So why is it important they know that? Uh huh, and why is that important?” (repeat as needed)

7.2.2. Break it down

7.2.2.1. Sometimes a topic is just too big to be precise. Once you start breaking it down, you can formulate much more specific routes and destinations to get where you need to go.

7.2.3. Sometimes there is no problem

7.2.3.1. Not all journeys are about the destination. Some are about taking a nice walk somewhere pleasant, or about getting in shape. Even when the learning isn’t in response to a problem, it’s likely to be in response to a need or desire.

7.3. Set the Destination

7.3.1. After you’ve defined the problem, you need to define your goal( s). The more specific you can be about this, the better you can design the path to get there.

7.3.1.1. Instead of using the word "understand" use "doing" words to describe the learning objective.

7.3.1.2. Use words like define, describe, and explain because those are observable actions— you can witness someone describing, defining, or explaining.

7.3.2. We don't care what they know, but what they can do. When creating learning objectives, ask . . .

7.3.2.1. Is this something the learner would actually do in the real world?

7.3.2.2. Can I tell when they've done it?

7.3.3. How sophisticated should your learner be?

7.3.3.1. Remember

7.3.3.2. Understand

7.3.3.3. Apply

7.3.3.4. Analyze

7.3.3.5. Evaluate

7.3.3.6. Create

7.3.4. How proficient should your learner be?

7.3.4.1. Familiarization

7.3.4.2. Comprehension

7.3.4.3. Conscious Effort

7.3.4.4. Conscious Action

7.3.4.5. Proficiency

7.3.4.6. Unconscious Competence

7.4. Communicating Learning Objectives

7.4.1. Reasons why

7.4.1.1. To focus the learner's attention on the key points in the objective

7.4.1.2. To let learners know what to expect

7.4.1.3. To let them know what level of performance they should be working towards

7.5. Determine the Gap

7.5.1. Once you've set your learning objectives, you want to revisit the question of why learners aren't currently meeting those objectives. Review "gaps."

7.6. How Long is the Trip?

7.6.1. How far can your learner progress down the path?

7.6.2. Pace layering

7.6.2.1. Some things change quickly

7.6.2.2. Some things change slowly

7.6.2.3. What is the pace layering of learners? What can change quickly, and what changes more quickly?

7.7. Summary

7.7.1. Use questions like “Why, why, no really, why?” and “What bad thing will happen if they don’t know?” to uncover the real reason for learning.

7.7.2. Define the problem before coming up with solutions, to ensure you are actually solving the real problem and not a problem you don’t have.

7.7.3. Use the two questions “Is this something the learner would actually do in the real world?” and “Can I tell when they’ve done it?” to make sure your learning objectives are useful and usable.

7.7.4. Decide how sophisticated your learner’s understanding needs to be, and how proficient they need to be, and then design accordingly.

7.7.5. Recognize if you are teaching someone a fast or slow skill, and use strategies appropriate to developing that type of skill.

8. 6. Design for Knowledge

8.1. Some of the Challenges

8.1.1. Will They Remember

8.1.1.1. Make Sure the Closet Ground is Fertile

8.1.1.1.1. Have Learners Consider What They Already Know

8.1.1.1.2. Have Learners Construct Their Own Framework of Shelves

8.1.1.2. Make It Sticky

8.1.1.2.1. Creating Friction

8.1.1.2.2. Show, Don’T Tell

8.1.2. Helping Your Learners Understand

8.1.2.1. The Right Amount of Content

8.1.2.1.1. The Average Attention Span

8.1.2.2. Misconceptions

8.1.3. How Much Guidance

8.1.3.1. How Do You Give Directions?

8.1.3.1.1. Step-By-Step Directions

8.1.3.1.2. If it’s too easy to follow the individual directions, then the learner won’t learn.

8.1.3.1.3. DYI Navigation

8.1.3.2. Applying The Learning in Multiple Circumstances

8.1.3.2.1. Option 1: Lots of Examples

8.1.3.2.2. Option 2: Concepts Followed by Examples

8.1.3.2.3. Option 3: Examples Followed by Concepts

8.1.3.2.4. Troubleshooting

8.1.3.3. Tell Them Less, Not More

8.1.3.4. Make Sure They Have Confidence In Their Ability

8.1.3.4.1. Ways for Learners to Gain Confidence

8.2. A Process to Follow

8.2.1. Micheal Allen's CCAF model

8.2.1.1. Context

8.2.1.2. Challenge

8.2.1.3. Activity

8.2.1.4. Feedback

8.2.2. The Scenario

8.2.2.1. Step 1: Determine Context

8.2.2.1.1. General Context

8.2.2.1.2. Emotional Context

8.2.2.1.3. Triggers

8.2.2.1.4. Physical Context

8.2.2.2. Step 2: Challenge

8.2.2.3. Step 3: What's the Activity?

8.2.2.3.1. Design Suggestion: use a pre-activity

8.2.2.3.2. Design Suggestion: Create E-Learning Scenarios

8.2.2.3.3. Design Suggestion: Use Role-Plays

8.2.2.3.4. Design Suggestion: Blended Learning

8.2.2.3.5. Design Suggestion: Follow-up Activities and Job Aids

8.2.2.4. Step 4: How Are You Giving the Learner Feedback

8.2.2.4.1. Feedback in the E-Learning Scenario

8.2.2.4.2. Feedback in the Role-Plays

8.2.2.4.3. Ongoing Coaching Feedback

8.3. Summary

8.3.1. Use strategies like recall of prior knowledge and metacognition to help support memory encoding and retrieval.

8.3.2. Some friction is necessary in learning. Just telling them is too smooth, and won’t stick. Learners frequently need to engage with the material to retain it.

8.3.3. Social interaction can be an effective way to add friction to learning.

8.3.4. Whenever possible, show, don’t tell.

8.3.5. The right content is less than you think it is, has enough detail but no more, and is relevant to the learners.

8.3.6. Starting with or using counter-examples can be a good way to prevent misconceptions.

8.3.7. Decide how much guidance you need to give your learners. Resist the urge to hold their hand at every moment.

8.3.8. A successful learning experience should leave the learner feeling confident and successful—“ like they invented calculus.”

8.3.9. You can use CCAF (Context, Challenge, Activity, and Feedback) to design effective learning experiences.

9. 7. Design for Skills

9.1. Developing Skills - 2 Main Components

9.1.1. Practice

9.1.1.1. Structuring Practice

9.1.1.1.1. What Happens To Your Brain When You Are Learning Something New?

9.1.1.1.2. How About When You Are Using Something You Already Know?

9.1.1.1.3. How Are Learning Experiences Structured?

9.1.2. Feedback

9.1.2.1. Frequency of Feedback

9.1.2.2. Variety of Feedback

9.1.2.3. Follow-up Coaching

9.1.2.3.1. Specific Criteria

9.1.2.3.2. Other Ways to Follow Up

9.1.2.3.3. A word about assessment

9.2. Design For Accomplishments

9.2.1. How Games are Structured

9.2.2. Timeframe Goals

9.2.2.1. Immediate Goal

9.2.2.2. Short-Term Goal

9.2.2.3. Medium-term Goal

9.2.2.4. Long-term Goal

9.2.3. How to Use This For Learning

9.3. Summary

9.3.1. Teaching skills requires two main elements— practice and feedback.

9.3.2. Learners will practice with you or without you, but you may not like what they are practicing when they do it without you.

9.3.3. Brain function gets more efficient with practice.

9.3.4. Avoid a steady stream of new information— it’s exhausting to your learners. Instead, build in opportunities for your learners to get a little proficiency with the new information before you move to the next element.

9.3.5. If you don’t give your learners a chance to rest, they’ll take it anyway.

9.3.6. Flow is a state of engagement that can be created through a balance of challenge and ability.

9.3.7. Space practice out over time.

9.3.8. Promote engagement by using structured goals and real accomplishments.

9.3.9. Use frequent and multifaceted feedback to shape behavior.

9.3.10. When assessing learner performance, have them perform the actual task whenever possible.