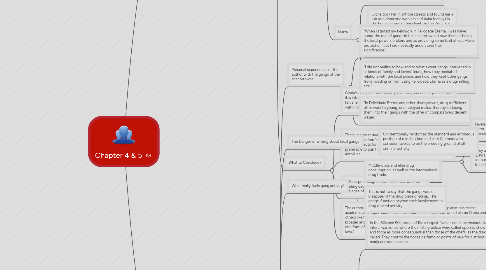

1. Chapter 4: No Time for Childhood

1.1. Pedro Paulo

1.1.1. PP was a fan of reggae music and highly politicized, particularly when compared to everyone else Diane knew. He was aware of the absurd nature of poverty in Rio.

1.1.2. His girlfriend was considered having an abortion and he threatened to kill her. He hated abortion and equally despised women who were not monogamous.

1.1.3. When Pedro Paulo died, Gloria ran into Gerson, Pedro's father. He'd never paid attention to Pedro Paulo or helped Gloria financially. Gloria ended their brief encounter by telling Gerson that tears weren't going to bring him back.

1.1.4. He believed the job of the man is to put the food on the table and as long as this is taken care of, it is fine for him to have as many women as he wants, as long as they don't lack anything, of course.

1.1.5. In 1995, he was killed in a shoot-out with police in Rocinha. Gloria considered him the most intelligent of all her children, he had completed his secondary schooling and could read and write at a relatively sophisticated level.

1.1.6. Men like PP felt that they had been cheated out of their own futures.

1.1.6.1. He figured out early on that those of his class and background do not have a great deal of social mobility. Those whom he knew in honest professions struggled to make a living.

1.1.7. Rio de Janeiro, is ultimately a city of pleasure for the wealthy, and Rochinha's position as a shantytown that borders the wealthy neighborhoods of the Zona Sul provides a stark contrast.

1.1.7.1. Here, children in difficult economic situations see wealthy children in the newest styles of clothes and sneakers. They watch them eating in restaurants, drivings in cars, and being spoiled endlessly.

1.1.8. As an intelligent young man, PP found the allure of the gang life to be irresistible.

1.2. Street Children

1.2.1. In May 1992, Newsweek ran a feature article titled "Dead End Kids" with the subtitle elaborating that about 200,000 Brazilian children live on their country's streets and are in danger of being slain.

1.2.1.1. In November, 1992, a group of young 'street boys' in Rio were lined up by members of a gang and shot in the knuckles supposedly to keep them from stealing too close to the favelas.

1.2.2. Each middle class person has his or her own strategic rationale toward the problem, ranging from refusing to give any money at all, since this won't solve the problem, to giving out money out of a deep seated fear or even as a kind of magical protector.

1.2.3. Hecht, 1998, makes an distinction between two forms of childhood in Northeast Brazil, the nurtured and the nurturing.

1.2.3.1. Nurtured

1.2.3.1.1. Coddled progeny of the middle-class families.

1.2.3.2. Nurturing

1.2.3.2.1. Poor children who from an early age take on serious responsibilities. They bring in resources to their mothers and nurture the household.

1.2.4. Mirelli

1.2.4.1. Gloria's goddaughter. Spent much of her youth at a FUNABEM, a state institution.

1.2.4.2. FUNABEM shows how Gloria and others like her evaluate the role of the state in their lives.

1.2.4.3. Mirelli's mother was 'lost' by her father in a card game.

1.2.4.4. Both her parents were alcoholics.

1.2.4.5. She and her two sisters would often eat leftovers from the garbage cans at luxury hotels in Sao Conrado.

1.2.4.6. Her mother died when she was 6.

1.2.4.7. She remembers being fondled by one of her mother's lovers while her mother was too drunk to notice what was going on.

1.2.4.8. Hecht finds that living on the street is much more difficult for girls than boys in the sense that the street transforms girls into mulheres or sexually initiated women.

1.2.4.9. During Mirelli and her sisters' time at the FUNABEM, they were taught to eat with a fork and a knife. They were also taken to excursions around Rio.

1.2.5. Lucas

1.2.5.1. Celina, Lucas' mother died and the children were to be divided among the respective godparents. This is termed child-circulation or child shifting.

1.2.5.2. Lucas lived in even more extreme conditions of poverty than Gloria.

1.2.5.3. Gloria did not tell the children that Lucas was their brother, they didn't recognize him from how malnourished he was.

1.2.6. Marta

1.2.6.1. Marta was a beggar, a street kid. She slept on the street and asked people for food.

1.2.6.2. Gloria took her in off the streets and found her a job as a domestic workers and baba (nanny) in the house of one of her clients in the Zona Sul.

1.2.6.3. Marta was going to be preparing food and caring for children who were approximately her own age.

1.2.6.4. Gloria felt that Marta needed to get used to hard labor, this was the only way she could train her away from the habits of the street.

1.3. What to Conclude?

1.3.1. Gloria's discipline was speedy, extreme, and nonnegotiable, and it is interpretable as part of a broader ethics of care that Gloria felt she needed to provide to ensure that her children survive within their present context.

1.3.2. There is a great deal of truth to Gloria's fears that if she cannot keep her children 'in line,' some of her boys, despondent about their prospects for low-paying wage labor, may find it preferable to join the local gang and get involved in its activities.

1.3.2.1. Favela gangs rule through violence, fear, and terror, but they often provide the only economic stimulus available to poor communities.

1.3.2.2. They are also perceived as protectors, especially against enemy gangs. Dilmar commanded an anti-beating law, which Gloria did as much as she could to dispel the allure of what she perceived to be false protection.

1.3.3. In Rio's poor neighborhoods, homicide is the leading cause of death for young men between the ages of 15 and 24.

1.3.4. The author concludes: "I wanted to offer some alternative explanations to the academic and upper-class discourse about child abuse that would blame Gloria and others like her for personal failings that may be better understood as caused by broader and more complex social problems." ... "I doubted that her promise to repay one form of violence with another was an effective way of gaining trust, loyalty, and love."

2. Chapter 5: State Terror, Gangs, and Everyday Violence in Rio de Janeiro

2.1. Personal experiences of the author with the gangs of the shantytowns

2.1.1. "When I started my fieldwork in Felicdade Eterna, I was naive about the role of gangs in the shantytowns. I saw them as being the local powers brokers and as providing some kind of local-level protection, but I did not really understand their significance."

2.1.2. "I did not realize to how and to what extent gangs intervened in all kinds of family and lovers' feuds, how they mediated relations with the local police, and how they kept other gangs from invading or from using Felicidade Eterna as a drug-selling site."

2.1.3. "In Felicidade Eterna and other shantytowns, drug traffickers offer work to young, unemployed males, thereby seducing them into their gangs with the offer of comparatively decent wages."

2.2. The Danger of writing about local gangs

2.2.1. Unintentionally reinforces the standard and erroneous position of middle-class and elite Cariocas who consider favelas to be the breeding ground of all criminal activity.

2.3. What really fuels gang activity?

2.3.1. Middle-class and elite drug consumption, as well as the international drug trade.

2.3.2. This is not to say that the gangs would disappear if the drug trade dried up. The gangs' function beyond their involvement in drug related activity.

2.4. Drug trafficking gangs and "police-bandits" in Rio: A history

2.4.1. In the 80s and 90s, some of Rio's largest favelas could be characterized as interal war zones where the military police were called upon to show their power and force as more consequential than those of the chefs, as the drug lords are called. They control the bocas de fumo or points of sale for distribution of marijuana and cocaine.

2.4.2. Drug chiefs are considered important local figures. They are homegrown and locally based, They provide badly needed services such as housing and cash in times of emergencies, as well as employment for youth.

2.4.2.1. Lulu and Ivo: Ivo was the Don before Dilmar and Lulu was a corrupt civil police officer.

2.4.2.2. Lulu's sister, Katy Mahoney was respected for being a touch woman who knew how to use force but who, despite her toughness, did not murder anyone. In this way, her reputation was distinct from that of her brother Lulu, whose only remembered feature was his marked corruptness.

2.4.3. Dilmar and Braga: Dilmar took over Felicidade Eterna in the 1990s and Braga 'cleaned up the area' and ironically eventually dated Dilmar's "woman" after Dilmar was murdered.

2.4.4. The term police-bandits as used by the residents of Felicidade Eterna, referred to their own sense of the inescapability of violence in the world.

2.4.4.1. It seemed to refer to the possibility that both of these entities inevitably played by the rules of revenge and personal reputation, and their blurring signaled the recognition by residents of the dysfunctionality of the system.

2.5. Justice in your own hands

2.5.1. Without social service institutions of the state made available to these populations, and without a reliable policing system, these kinds of problems create their own cycles of revenge and involve gangs as hands-on substitutes.

2.5.2. Sexual Abuse

2.5.2.1. In 1998, a man was discovered to be raping his step-daughters. He felt that if he was financially supporting them, no one else should get to 'eat' them. When word of this spread, gang members went to his home and severely beat him, threatening him with death if he returned. Residents felt there was no other way to deal with this kind of criminal.

2.5.3. Gun Control

2.5.3.1. When ADA invaded Felicidade Eterna, it prohibited residents from owning a gun who were not part of a gang.

2.5.4. Rape of a child

2.5.4.1. A case of mistaken identity caused a man who was completely innocent to be set on fire and badly burned. A child was raped and a local gang made it their goal to kill the rapist, unfortunately, they did not care that the man they mistakenly captured was not the perpetrator. They still set him on fire.

2.5.5. Politics

2.5.5.1. Two paradoxes : the state tolerates a corrupt and extraordinarily violent military and civil service bureaucracy; and second that the high levels of police violence have not been adequately protested in part because of a popular support for policies that appear to be tough on crime.

2.5.5.2. The point here is that the population's support for police violence indicates the existence not only of an institutional dysfunction but also of a pervasive cultural pattern that associates order and authority with use of violence.

2.5.5.3. The lower classes fear and distrust of both the civil and military police are extreme.

2.5.5.4. Those who speak in defense of human rights are viewed as supporting the priviledges of the bandidos.

2.5.5.5. Poor are seen as being naturally guilty of criinal needs while the crimes of the wealthy are seen are part of a larger less controllable system.

2.5.5.6. Mafia: was the sort of code of behavior which always tends to develop in societies without effective public order.

2.6. Conversion to Religion

2.6.1. It seems as if women are choosing religious conversion as a form of oppositional culture, one that resists male oppositional culture, namely gang membership.

2.6.2. Often, conversion is a form for the poor to decriminalize themselves in a society that criminalizes them.